With Microsoft amassing studios for its Game Pass kingdom and many of the industry’s big players chasing cloud streaming, will a “Netflix of games” ultimately come along and squash a la carte game purchasing, tying us all to subscriptions forever? Industry analyst Piers Harding-Rolls is skeptical.

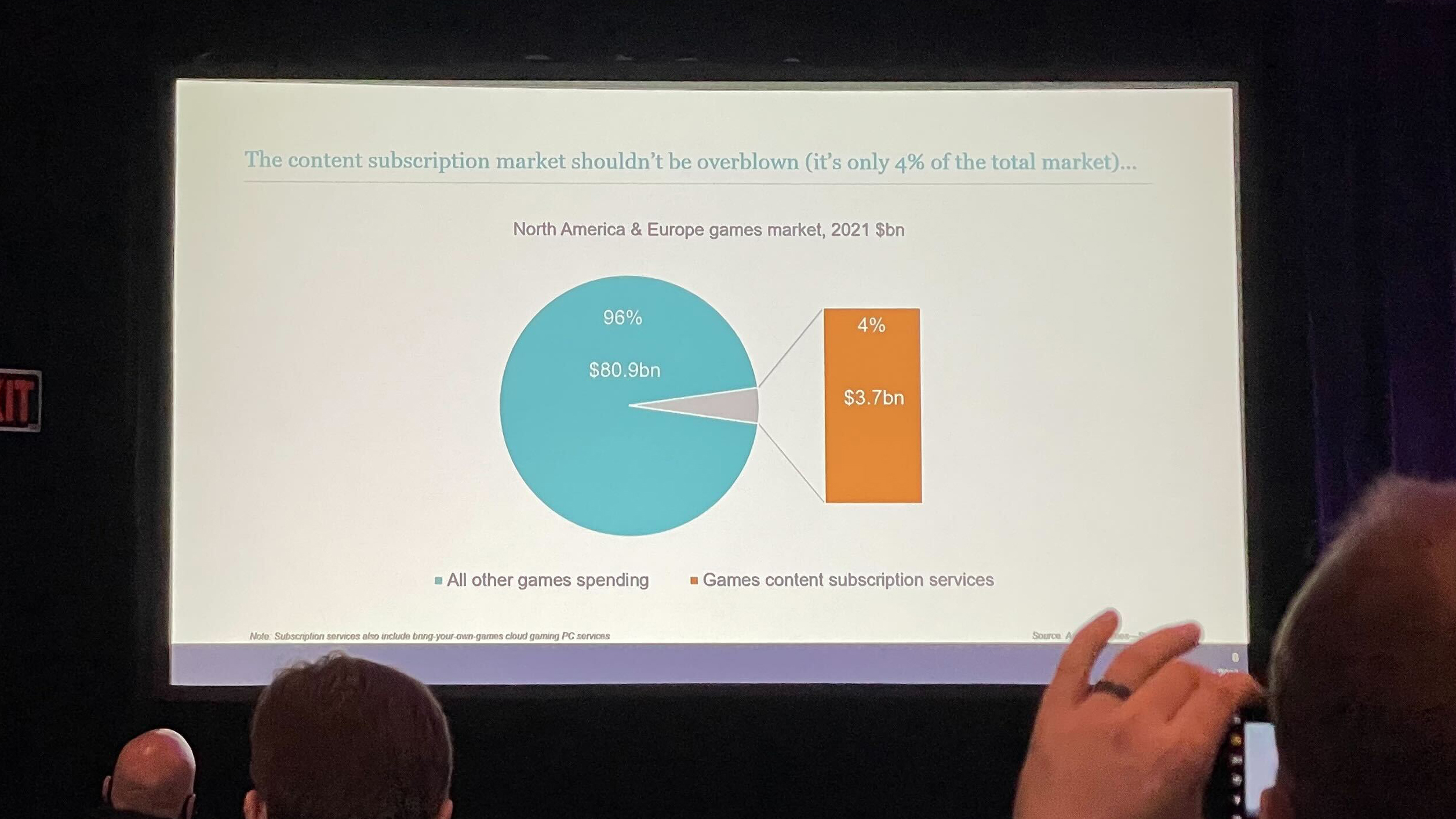

At a GDC 2022 talk on Wednesday, Harding-Rolls advised game developers to keep the rise of subscription services in perspective by considering that it’s currently a much bigger topic of conversation than actual industry sector: According to data firm Ampere Analysis, where Harding-Rolls runs game research, subscriptions currently account for 4% of the total games market. He forecasts it’ll be 8.4% by 2027—a significant amount of money, but still a small slice of gaming as a whole.

Harding-Rolls also points out that the total number of Game Pass games is fairly small and hasn’t been growing much recently. After EA Play games were added in March of last year, the service has hovered at just under or above 500 games. The success of Game Pass is attributed primarily to the newness of the games available on it. (Especially compared to PlayStation Now, which offers more but older games.)

Netflix started small, too, and now has over 200 million subscribers, but Harding-Rolls points out that games and videos are different from each other in some important ways. The biggest is that, as a category, games today make most of their money after people are already playing them. According to Ampere’s data, 79% of games spending in 2021 came from in-game transactions in free-to-play and paid games. That kind of behavior doesn’t exist for Netflix or Spotify.

According to Harding-Rolls, people who use subscription services spend more on average on full games, expansions, in-game purchases, and season passes—they just buy more overall, on top of the subscription fee. Asked whether that was because subscription services attract people who already play a lot of games or because the services somehow influence subscribers to spend more, he speculated that it was a mix of both. One likely influence is that subscribers have a reason to try out new games that non-subscribers don’t: They’re already paying for them.

Whatever the case, Harding-Rolls doesn’t buy the idea that we’re on the verge of a Netflix-like takeover, even as Netflix itself gets into games. “I don’t believe that subscriptions will become the dominant monetization model in the games sector as it has done progressively in the video and music sectors,” he said.

Free-to-play games certainly aren’t going anywhere, although if we reduce the scope of our thinking to the kind of games that are most relevant to subscription services—games that aren’t free-to-play—I don’t feel confident that $60 purchases will be the typical way we acquire them in 10 years. But Harding-Rolls makes a fair point in saying that games aren’t movies, a fact I’ve been guilty of brushing aside when feeling trepedatious about Game Pass. It has to be too simple to say, ‘Well, it happened for movies, so it will for games, too.’ For one thing, we already aquire nearly all games as downloads on PC rather than on physical media, so the rise of Game Pass doesn’t map at all cleanly onto the demise of video stores.

And while we’re easing fears, I’d add that people do still rent and buy movies, digitally and physically. Subscription streaming accounts for more than half of home entertainment revenue, but according to the Digital Entertainment Group (via Variety), US consumers spent $5.9 billion on Blu-rays, DVDs, and a la carte digital video purchases in 2019, and $3.4 billion on rentals. Those numbers are decreasing every year, but still: The things video streaming subscriptions are supposed to have killed a long time ago are still kicking.