The Stinking Cloud spell sees a lot more use in the Gold Box games than it ever does in a typical Dungeons & Dragons session. When you’re sitting around a table pretending to be an impressive wizard, summoning a sphere of what is basically toxic fart gas isn’t your usual go-to. In 1988’s Pool of Radiance, the first game SSI published in an iconic golden package, enemies wouldn’t walk into a Stinking Cloud, making it a powerful tool for area-denial available to your otherwise kind of useless level 2 magic-user—so long as you didn’t accidentally catch the front-row fighters in it.

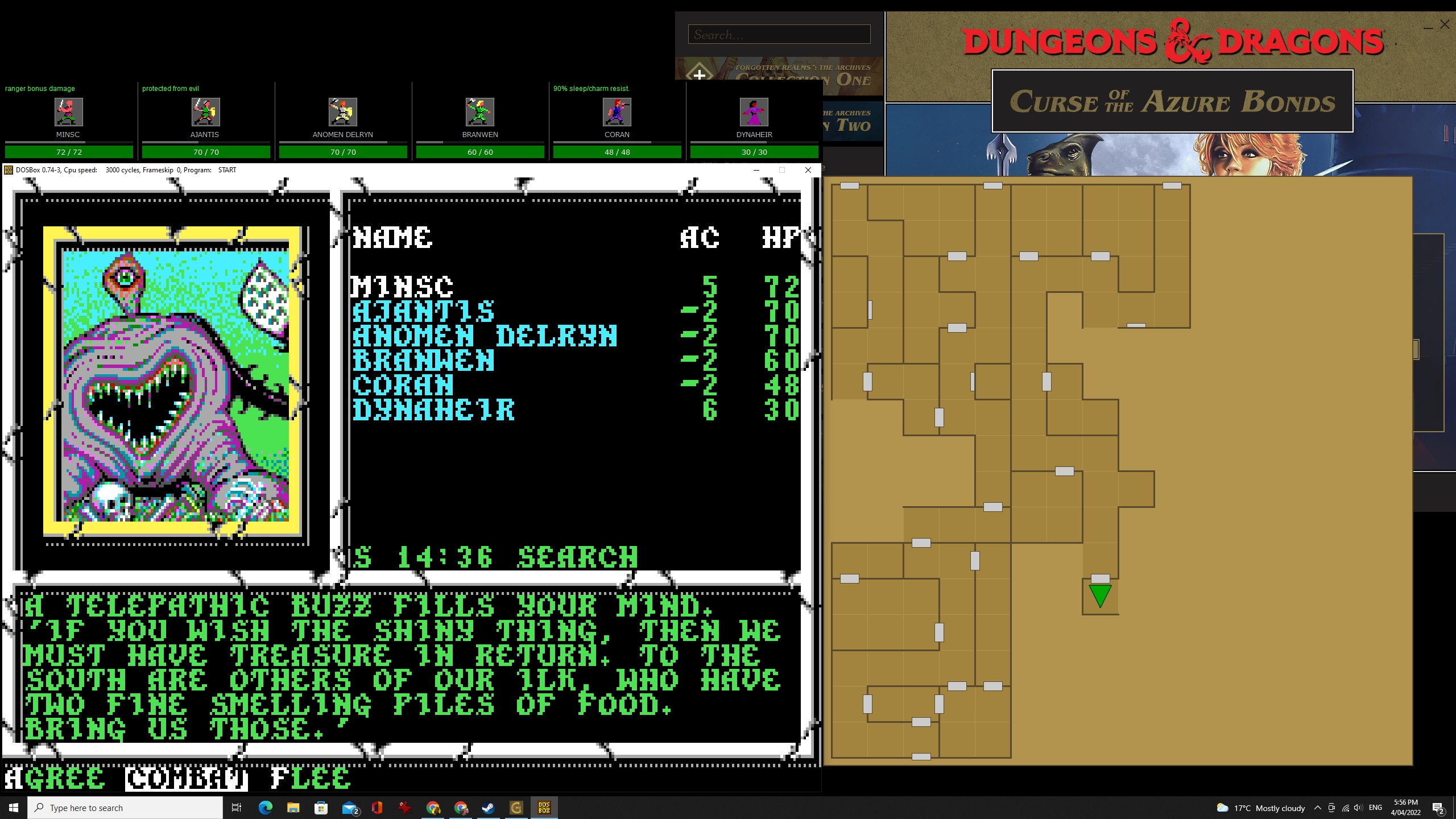

Though the monsters were a little smarter in Pool’s 1989 sequel Curse of the Azure Bonds, and would risk charging through a Stinking Cloud rather than let your party stand on the other side shooting arrows +1 all day long, the spell was still likely to leave them nauseated and helpless, able to be slain “with one cruel blow” as the memorable description put it, by anyone who walked over to stab them. Even a level 2 magic-user.

There were two reasons Stinking Cloud—and the other low-level area-of-effect spell Sleep—were mainstays of the classic Gold Box games. The first was that these games had turn-based tactical combat with enough depth that penning in enemies was a naturally occurring tactic. With a party of six player-characters, plus one or two NPCs, it was easy to block corridors and force kobolds to come to you. Bunched up, they became perfect targets for big spells, as well as the fighter’s sweep attacks, and maybe a cheeky backstab from your multiclassed fighter-thief.

The other reason they were essential was that so many of the other spells were useless. The Knock spell let you open locked doors, which any fighter could do with a bash, Protection From Good was pointless because most of the enemies were evil, Detect Invisibility and Reduce were so situational that memorizing them was a waste of time, and Burning Hands only did one point of damage per level and had a range of “basically fucking”.

Those spells were included because the early Gold Box games were as true to the then-current Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 1st Edition rules as they could be. It’s the same reason they had harsh level caps for non-human characters, constant resting to memorize spells, having to pay a trainer every time you wanted to level up—all authentic elements of AD&D back in the day, all a total drag.

Which games count as Gold Box?

The name Gold Box refers both to the boxes some of SSI’s games were released in, and the name of the engine they were made in. Confusingly, not every game made with the Gold Box engine was released in a gold box, and which games should be counted depends who you ask. The bundle of Gold Box Classics SNEG released on Steam doesn’t include the 1991 online game for obvious reasons, or Spelljammer or the two Buck Rogers games made in the engine but not published with gold boxes, yet does include the Dark Sun, Ravenloft, and Eye of the Beholder series, as well as Menzoberranzan and Dungeon Hack, none of which were given gold boxes or made with the engine. SNEG also rereleased Al-Qadim: The Genie’s Curse and Stronghold, which use the same launcher, but didn’t include them in the bundle. It’s confusing.

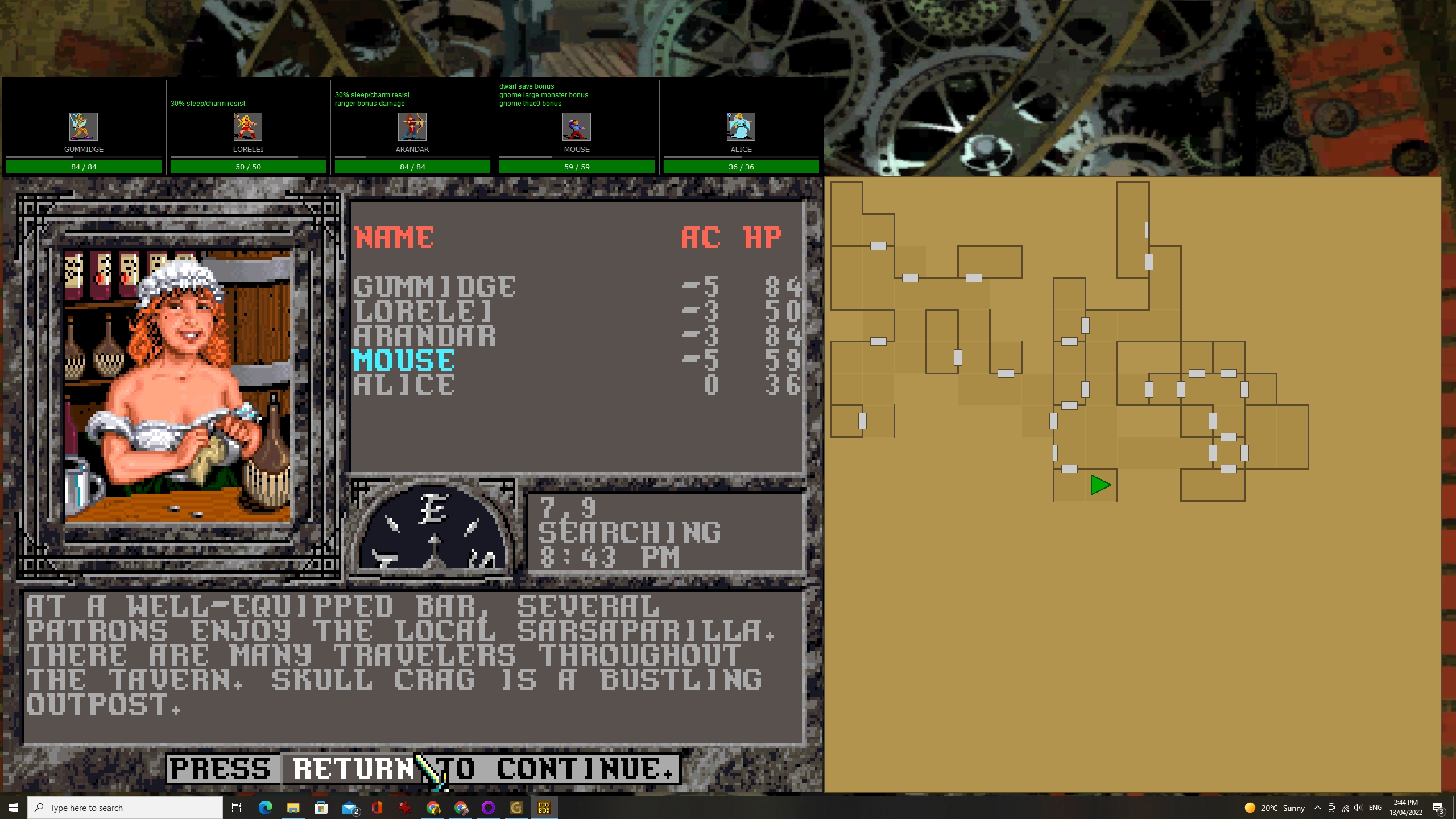

When we played these games in the late ’80s and early ’90s, we had to put up with that stuff. Thanks to the Gold Box Companion, modern players don’t. The work of Joonas Hirvonen, who also created the All Seeing Eye companion apps for the Eye of the Beholder series, the Gold Box Companion snaps a menu to the top of the game window that shows summaries of your characters, complete with HP and XP bars, and gives access to a suite of options that include leveling up away from the training hall (while also ignoring race-based level caps), storing the spells you’ve currently got memorized then restoring them with one click, automatically identifying magic items, restoring lost levels to characters who’ve been drained, and so on.

Where the original games were strict interpretations of the rules as written, having the Companion is like playing D&D with a Dungeon Master who skips the boring stuff and ignores the more unfair rules, which actually brings it closer to the real experience of playing D&D. Even the annotatable automatic map snapped to the window’s right is like having the kind of DM who just uncovers the dungeon on the table as you explore. That’s how I do it, because the thought of forcing my friends to draw on graph paper while I recite the exact dimensions of every room makes me want to eat a bullet.

What’s different in the Steam versions?

While the Gold Box Companion has been around for years, SNEG’s Steam release of the Gold Box Classics, which also throws in the Eye of the Beholder series and a few other games, comes with updated versions of the Companion and the All-Seeing Eye preinstalled. These versions of the apps are paired with a launcher, which means they open automatically rather than needing to search for your savegame every time. The Companion also has a new option to change the games’ font, and the launcher lets you easily reconfigure the window size to make room for the add-ons. On my 1440p monitor, running them at 1080p is a snug fit, with a little room at the top for my wallpaper to peep over.

I played the GOG versions of these games a few years ago, downloading the Companion separately. The standalone version may have lacked the font-changing and needed more faff to get running (using GOG Galaxy’s graphics mode setup I set the scaling engine to normal2x, then realized everything looked too wide and went back to tick the Keep Aspect Ratio box), but it did have some extra options. Namely, a character editor, save editor, teleporter, and more character classes so you can play paladins and rangers in Pool of Radiance rather than waiting for them to be added in Curse of the Azure Bonds, as well as an experimental monk class that was never part of the videogames.

The standalone Companion was a more powerful toolset, but I eventually ended up with corrupted saves both times I used it, so I can see why the Steam version has been streamlined to prevent you monkeying around as thoroughly with your files.

If you want to try some of those options in the Steam release, Joonas has uploaded a couple of Steam extras. One download adds the character editor and an “explore map” button, another adds playable paladins and rangers to Pool of Radiance. A third bolts onto Forgotten Realms: Unlimited Adventures—a DIY scenario design kit released in 1993 that lets you create your own Gold Box adventures—making it easy to install modules constructed by fans.

A sizeable fan community has been making modules for Unlimited Adventures over the years, so there are plenty to choose from, including adaptations of classic D&D scenarios like The Keep on the Borderlands as well as remakes of the earlier Gold Box games. If you can’t bear to play Pool of Radiance without mouse controls and more than 16 colors, playing it inside Unlimited Adventures is another option. The fan versions also restore the theme music to it and Curse of the Azure Bonds, a banging tune that’s sadly been removed from both the Steam and GOG releases.

A whole world in a box

Even with the Companion, it’s worth being warned these are clunky games. They use the numberpad for almost everything, which means navigating menus using 1 for down and 7 for up. (Page up and page down work as well, as I’ve just learned decades too late.) Treasure includes six varieties of coin, and if you can remember off the top of your head that 1 platinum coin is worth 10 electrum coins, which is equal to 5 gold coins, or 100 silver coins, or 1000 copper coins, you’re doing better than me. All those coins have encumbrance, and you end up abandoning piles of money to avoid being weighed down by it, which doesn’t matter because there’s hardly anything worth buying anyway. Every weapon shop’s inventory includes an overlong list plumped out with every kind of polearm in D&D, none of which you’ll ever need.

So what made them classics, and why would anyone want to play them today? The turn-based tactical combat I rhapsodized about above is a huge part of it, and combat makes up the majority of what you’ll be doing. Some of the spin-offs went real-time though, with Al-Qadim: The Genie’s Curse closer to a Legend of Zelda game, and others were first-person blobbers like Eye of the Beholder. On that subject I bow to the expertise of my esteemed colleague Andy Chalk, who says everyone should play Eye of the Beholder 2: The Legend of Darkmoon.

Beyond the combat, a significant part of their appeal is down to their unique vibe. The journals are responsible for a lot of that, full of text and sometimes diagrams that wouldn’t fit on the floppy disks. Everything from overheard tavern gossip to excerpts from books found in a haunted library or crude maps drawn by monsters—all of it could be found in the journal, which you’d be directed to from the game with notes like, “You find information on his body and log it as Journal Entry 4.”

Compared to the terseness of most in-game writing at the time, all-caps and brutally edited to fit text boxes, the journal entries were verbose and characterful, whether evoking a haughty villain’s speech or a spy’s summary of nearby threats. The writers clearly had fun with them, even adding entries that weren’t pointed to from anywhere in the games, written to lead astray anyone who tried to cheat by reading paragraphs they hadn’t been told to.

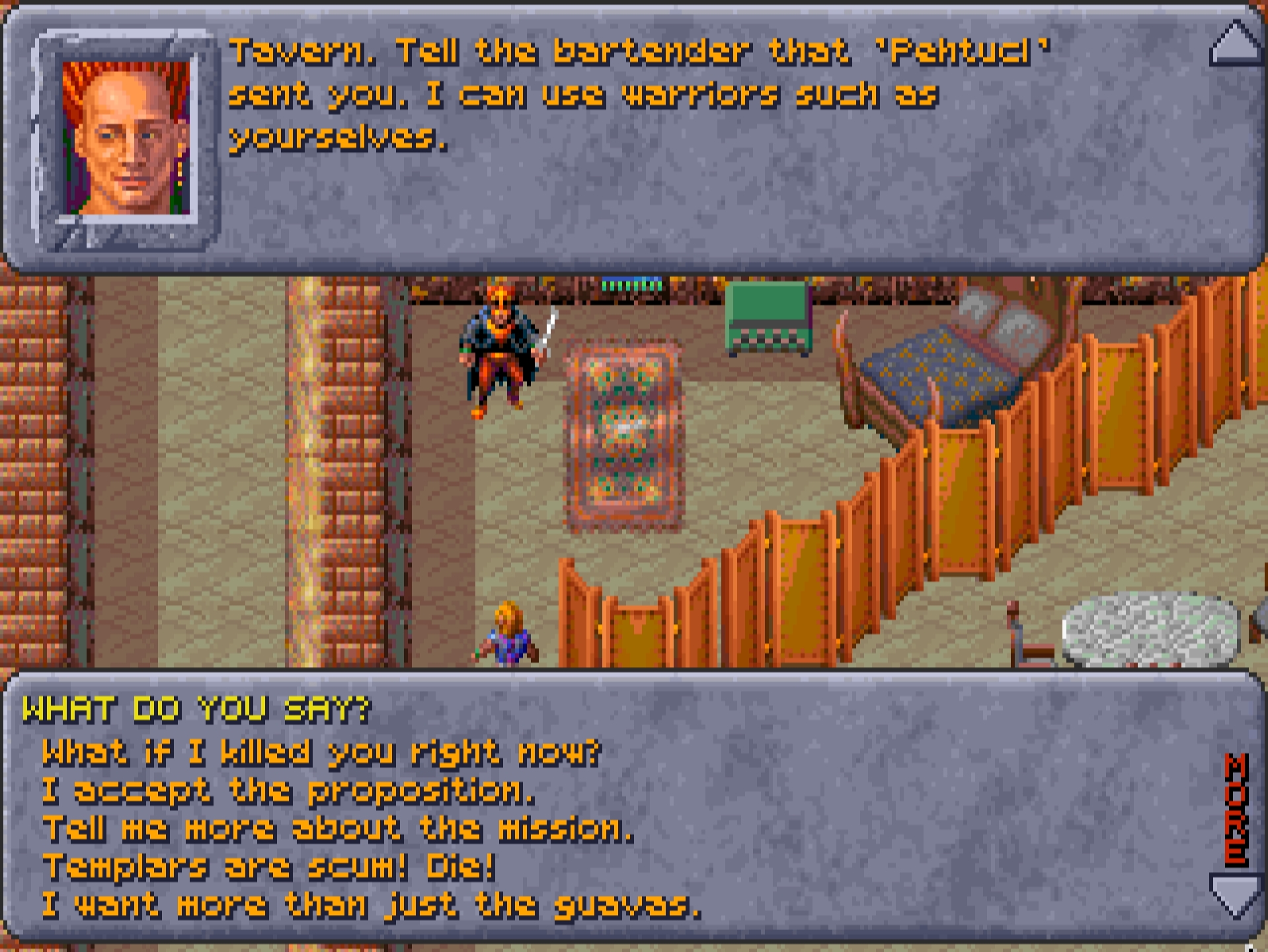

The in-game writing was more basic, though you could parley with monsters, which meant guessing which attitude from choices like haughty, meek, nice, or abusive would be best for dealing with hobgoblins. One major villain turned it around and parleyed with you, delivering a “You should join me!” speech that let you respond separately for every character in your party. (Anyone who said yes became an NPC in the final fight.)

Though the graphics were rudimentary, and the later Gold Box games were outclassed by their contemporaries, seeing animated versions of monster art based on the illustrations from the Monster Manual made it feel like you were playing D&D in a way later adaptations like Baldur’s Gate didn’t. The heroes on the other hand had sprites you got to design, which made every adventurer feel like they were yours. The fact they were just a handful of pixels meant you never had to worry about making a character only to realize hours later their mouth looked weird in cutscenes.

Choose your own adventure

The final, vital aspect of the Gold Box vibe was that the best of them gave you freedom to plot your own way path. After a linear opening in which you’re cursed with a bunch of magic tattoos, Curse of the Azure Bonds set you loose on an overworld map to remove them in whatever order you chose. Pool of Radiance was all about taking back the town of Phlan—a name I could never take seriously—and its surroundings from monsters who had driven the inhabitants out. It was a stack of missions could be tackled however you chose.

That said, going anywhere undead had made their home before you were ready was a bad time, and trying to clear out the trolls in Phlan’s Rope Guild when you were only level 1 or 2 was an exercise in futility, no matter how many Stinking Clouds you were packing. And the “find the plot yourself” nature of Heirs to Skull Crag (the default module included in Unlimited Adventures) and some of the Krynn games made them harder to get into.

The Gold Box games were leagues ahead of most other RPGs when they were new, but they weren’t without problems. They struggled to improve on their early successes too, which is why I’m almost exclusively talking about Pool of Radiance and Curse of the Azure Bonds. In 1992, Treasures of the Savage Frontier added weather effects and one of the first romanceable companions in an RPG, but real change only came when SSI moved on from the Gold Box engine.

The future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be

In 1993, SSI released Dark Sun: Shattered Lands, which made dialogue choices frequent and important—sometimes offering different ones based on what kind of characters you’d made. Problems could be solved in multiple ways, with alternatives presented naturally. After being captured and forced to fight in a gladiator pit, you could win battles to impress one of the prison gangs until they let you in on their escape plan, or find a jewel to bribe a guard, or heal an amnesiac who’d escaped once before but had the memory removed. Not every option was equally good, but you were free to pursue whichever appealed, or even combine a couple of them.

The SNEG re-release includes several games that weren’t technically Gold Box releases, like the Dark Sun series, and I’m glad of that. The older games are historically significant, and I feel a rush of nostalgia whenever the big skull and crossbones appears when you kill a monster, but taken on their own I could see them seeming like a dead end—a series that started stronger than it ended, and fell into repetition halfway through. By including games like Dark Sun: Shattered Lands, they make it clear there was innovation going on, and make the connection between these RPGs and those of the later ’90s like Fallout much more plain.

And as well as pioneering the branching dialogue trees and avenues of choice that would become standard in the better flavor of modern RPG, Dark Sun: Shattered Lands also added a clearly readable spell effect marker so you always knew who’d be hit by a Stinking Cloud.