I have to admit that I was surprised to see the hooded figure of Garrett, Master Thief, reaching covetously for me from the free game section of the Epic Games Store, not least because Epic’s giveaways tend to focus on relatively recent games (barring bona fide classics), but also generally well-liked ones. And scouring through the online discourse in the years since its release, people really don’t seem to like the 2014 reboot of Thief.

The original Thief and Thief 2 were masterpieces of lo-fi stealth and level design, boldly imposing a slow pace, lack of combat, and rigorous stealth systems at a time when the first-person perspective was largely reserved for blindingly fast and brutal shooters. Deadly Shadows, released in 2004, was far more disjointed, but had its merits too, including one of the greatest videogame levels. Thief (2014), meanwhile, melded the vintage elegance of Thief with some of the bad habits of early 2010s game design. It certainly is an odd duckling.

For every satisfying swipe of a gold watch, slick intrusion into a gorgeously designed mansion or bank, or dash into the darkness just as a guard relights an extinguished torch, there were QTE set-pieces, restrictive traversal controls confined to specific grappling, climbing, and jumping points, flow-breaking cinematics, or pointless villain appearances to pull you out of the thieving fantasy. The story—from the moment Garrett condemns his protégé to death by stealing a grappling hook gizmo off her because it was too loud, before muttering to himself “Huh, actually this is quite useful, I think I’ll keep it”—is so bad it’s hard to get more out of it than just a chuckle at its expense. Even that might be difficult for long-time fans likely to be offended by it totally binning the intriguing lore of the earlier games.

To many, Thief (2014) is a game best forgotten, squeezed out of memory by its legendary lineage on the one hand, and Arkane’s Dishonored series on the other, which had far more success in modernising Looking Glass Studios’ design philosophy. But assuming you’ve played the original Thiefs (Thieves? Thiefses?) and Dishonored to death, there’s something worth going back to here, now that its launch-day bugs and performance issues are long gone and, well, it’s available for free (until April 11). Thanks to an impressive number of difficulty and HUD options, it’s even possible to tweak it to be more in line with the classic Thief experience.

See, by default, Thief (2014) is guilty of the kind of patronising hand-holding that plagued triple-A games of the late 2000s to early 2010s. Interactable surfaces glow blue, directing you to possible pathways, grappling points, and routes from a distance; this is usually layered over with objective markers that, in some cases, hover directly over said luminous points, just in case the screamingly obvious visual cues weren’t obvious enough (even without all the overlays, you still have white paint splatters to indicate grappling points).

Then there’s the focus button, essentially an x-ray mode that eradicates your remaining autonomy by temporarily highlighting every single interactable thing in sight. With focus upgrades, you can further dumb the experience down by unlocking ghostly handprint trails leading to treasure, turning regular arrows silent, visually seeing footstep sounds through walls, and one-shotting alerted enemies with your blackjack, among other powers. All of this nonsense is cheating you out of what is, at its core, a really solid stealth experience.

It makes the game feel more linear than it actually is, too, undermining much of Eidos-Montreal’s fine level design and art direction. The degree to which you’ll want to trim the HUD fat will vary, but it really speaks to the weird tension at the heart of Thief (2014)—that desire to retain the spirit of the originals while trying to appease some mythical mainstream audience that was presumably identified by the publishers—that the game lets you turn these additional layers off, and is much better once you do.

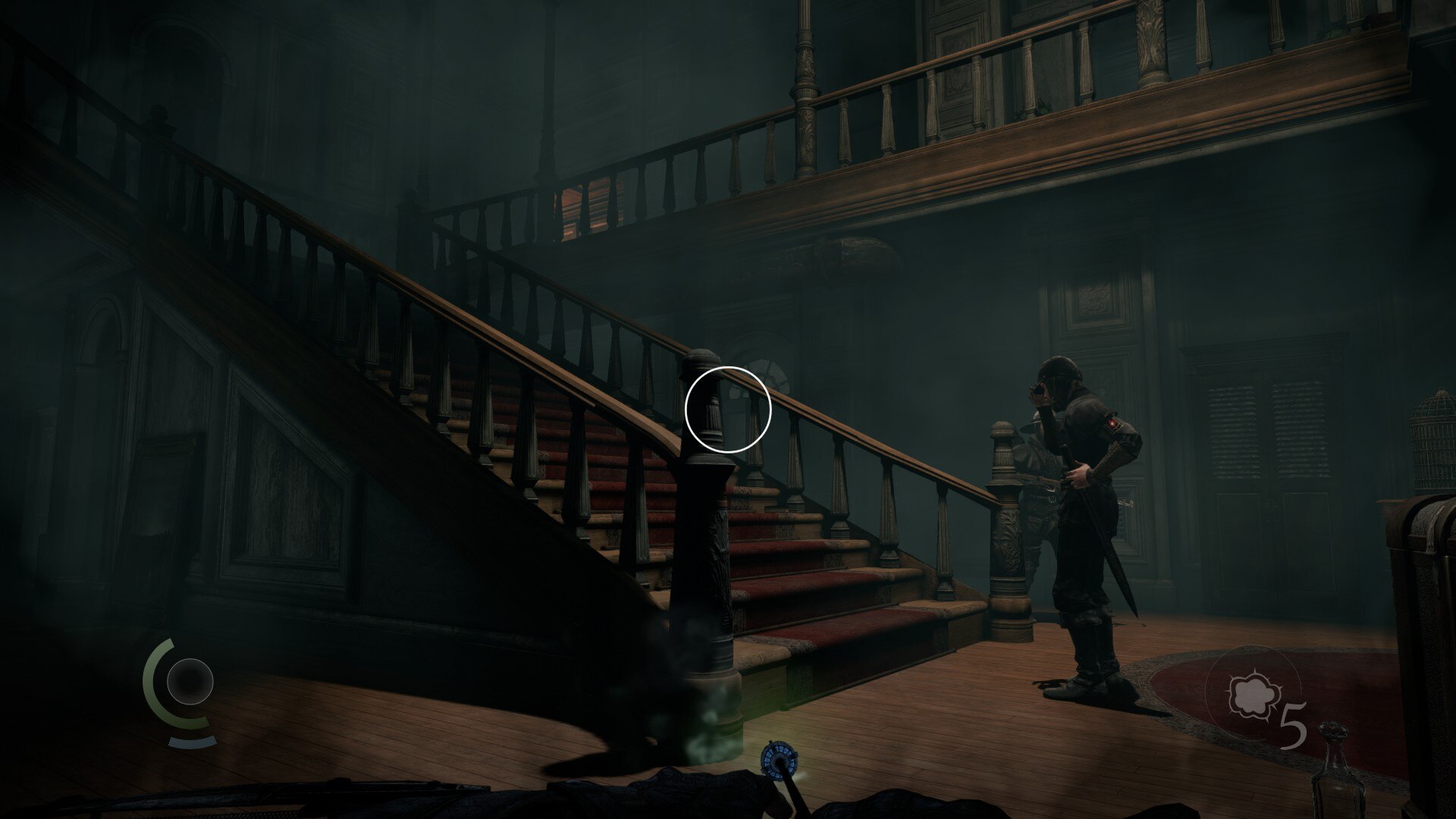

There are some fantastic levels in the game’s campaign—chief among them a brothel, a couple of ornate mansions, and a bank heist—that for decent chunks of time immerse you in the simple act of sneaking through shadows and getting your dainty, beautifully animated hands on whatever loot you can find. Each of these levels has multiple points of entry, secrets to uncover by eavesdropping or notes lying around, and neat little puzzles. It’s worth stressing also that the gloomy, damp world—a tasteful blend of Tudor England and steampunk Victoriana—still looks gorgeous today, bolstered by the ease with which a modern machine can run the game in 4K resolution.

There’s a real elegance to Garrett’s movements as he peels back curtains, places his hands on corners and parapets, searches for secret switches behind paintings, or picks locks. Movement feels smooth and deliberate. It’s a shame, though, how frequently the game pulls you out of this experience to throw you into some Assassin’s Creed-style third-person ledge-shimmying, or decides that you can only clamber certain surfaces and only jump onto certain obstacles, or puts Garrett in front of the camera when the poor guy is clearly so much more comfortable behind it.

Even the best missions invariably end with a chase sequence or explosive set-piece. It’s like the game follows one of those weird action-movie rules about ‘something big needs to happen every [x] minutes’ even though Thief (2014) is neither movie nor an action game. One of the game’s best designed levels, Baron Northcrest’s mansion, ends with a barely interactive sequence of you escaping for 10 minutes as the whole building collapses around you, before watching it all burn to the ground. It’s a perfect representation of how the game keeps building itself up, only to tear itself down again.

That’s why the side-jobs are such a joy. These condensed little missions assign you to steal doodads for various clients, and in some cases take you to new levels—well structured little shops, dens, small homes—you’d otherwise miss. With no detours into cutscenes or contrived chase sequences, you can go about the simple, satisfying business of thieving, and experience the game’s excellent core mechanics and light-and-sound systems at their best. You can also just run around the city between missions, parkouring (quite restrictively) over rooftops and breaking-and-entering where you see fit. Again, isolated from the story, Thief (2014) thrives.

There are plenty of great touches here. Trained on games where enemies’ lines of sight are myopic vision cones that cut off after 15 metres, I was surprised that guards could spot me all the way across a large well-lit room, but of course that’s much more realistic. They’ll notice open doors, chests, and looted safes, and will even lean through windows or peer over ledges when looking for you, a clever touch you rarely see even in modern stealth games. These guys are perceptive. As a Hunt: Showdown fan, I also appreciate the little details, like caged birds, dogs, and broken glass as extra obstacles to be mindful of, as well as how physics objects in the world like brooms, cups, and glasses can give you away if you bump them over. I had a good couple of moments where I fumbled a perfectly executed stealth manoeuvre at the last second by kicking a cup on the floor, or knocking a vase off a table, creating emergent, tense scenarios where I had to think fast to stay hidden.

There’s one moment that probably best sums up my bittersweet feeling towards Thief (2014). At one point, a grumbling guard refers to someone as a taffer—a great little curse-word invented for the Thief universe back in the original games, and something of a calling card for the series. 10 seconds later, that same guard drops an F-bomb, as if suddenly remembering that he’s in a game that has to appeal to the (imagined) edgy kids playing the game in 2014, as if the wonderfully evocative ‘taffer’ just wasn’t enough. It’s indicative of how Eidos-Montreal lacked confidence to follow through with an unadulterated Thief game, reaching for the low-hanging fruit of what ‘modernity’ meant in games a decade ago.

I don’t doubt that the studio was well versed in the spirit of the series, but had to balance that against what publisher Square-Enix—which always seemed uncomfortable with managing immersive sim IPs like this, Hitman, and Deus Ex—thought would make the game sell (and in fairness, the game did actually sell quite well). There’s a good reason Square-Enix relinquished the Thief and Deus Ex IPs for a bargain price to Embracer Group in 2022, while Hitman broke away from the publisher sooner and has enjoyed plenty of success since. Immersive sims were never a comfortable fit with a predominantly JRPG publisher.

Sadly, Embracer seems like to much of a trainwreck right now to do right by the series either, but there are enough glints in the darkness of Thief (2014) to convince me that, with the right publisher, Eidos-Montreal could still deliver us a great Thief game one day.