Introduction

On Halloween night, 1997, when most kids were out trick-or-treating and teepeeing houses, I was locked in my bedroom with the lights turned off, hunched over a 40-pound CRT monitor, obsessing over every pixel of Riven: The Sequel to Myst.

I discovered five islands ripped apart by mysterious forces. An ancient civilization with the power to create bridges between worlds with books. A man who believed he was a god. A woman determined to free her people.

Over the next few weeks, I pulled levers, pushed buttons, and unlocked doors until I heard their steam-powered pneumatics in my sleep. I read every journal left behind by the people who lived in Riven. I said “Oh my God” out loud at least a dozen times and gasped in surprise just as often.

If Myst was The Hobbit of point-and-click adventure games, Riven was The Lord of the Rings. Built by a small studio called Cyan in Spokane, Washington, it had photorealistic graphics on par with its era’s Hollywood movies and the narrative intricacy of a novel.

But for many people, it was more than just a technical marvel. It was a life-changing experience.

“I can directly trace my path to the gaming industry back to Riven,” says Sam Winkler, narrative director at Gearbox Software and co-writer on Borderlands 3.

“I often credit Myst and Riven as the main inspiration of my creativity today,” says David Howe, lead editor of Netflix’s Castlevania series.

An engineering lead on Diablo IV, Jeff Stewart, says Riven was “the single most inspirational game” he ever played.

But in 1998, a few months after Riven came out on October 31, 1997 – before it sold 4.5 million copies and became the runner-up to Myst as the best-selling PC game of all time until 2002 – the game’s three creative leads parted ways.

Rand Miller, the developer who played franchise protagonist Atrus on-screen, stayed at Cyan and became CEO of the oldest surviving independent game studio in America. His brother Robyn Miller, the artist and composer behind many of Myst and Riven’s sights and sounds, left the company to pursue other interests. Richard Vander Wende, the production designer of Disney’s Aladdin who pushed the Millers’ sequel to new heights in iconic imagery and character-driven realism, went back to the film industry.

Two decades passed before Rand Miller asked a question.

What if we went back to Riven?

And then, What if we made it bigger and better?

Rebuilding A World

Rebuilding A World

Twenty-six years after the original Riven was released, I arrive in Spokane at the peak of autumn, when the forest surrounding Cyan’s headquarters is bright with red and gold leaves. I immediately recognize the front door from Richard Kadrey’s 1997 coffee table book, From Myst to Riven – an otherworldly arch that looks like it was torn away from the rest of the Arts-and-Crafts-style building by an earthquake.

“The bricklayers loved that,” the voice of Atrus tells me. “They said it was the most fun thing they’d ever done.”

In person, Rand Miller doesn’t remind me of the bespectacled scholar (and questionable father) he’s played in six consecutive Myst games. Now 64 years old, with long locks of gray hair and a penchant for Birkenstocks, Miller exudes the easygoing and paternal warmth of a surfing instructor. He speaks with the slightest hint of a southwestern drawl, no doubt from his years living in New Mexico and Texas.

Miller shows me around the House That Myst Built. I see mannequins dressed in costumes from the original Riven, a display case full of awards, and a massive knife prop built by Adam Savage before Mythbusters made him famous. In the back of the building, overlooking an algae-filled pond and a grove of ponderosa pines, we reach a conference room with a cyan-blue ceiling.

“Why remake Riven after all these years,” I ask.

Miller takes a deep breath. “Riven was sacred to us, so we waited until the technology finally caught up to the point where we could make something that looked even better than the original, but in 3D,” he says. “[And] my first thought was, we need to make it look precisely the same.”

But then Miller reached out to Vander Wende, the original game’s co-director, with a tantalizing question: “If you could change anything about Riven, pie-in-the-sky, what would you change?”

Vander Wende arrives at Cyan a little later in the morning, fresh off a plane from Hawaii. He’s in his 60s now, too, and tall like Miller but more soft-spoken. He also sounds like every bit of the perfectionist he was in the ’90s.

“I can’t do something half-assed unless somebody puts a gun to my head,” Vander Wende says. Turning to Miller, he continues: “I was really dubious when you approached me about coming back to Cyan. Why would I want to remake something I already did? I never even played the original game after it came out. Doing an imitation of it held no interest for me.”

As a result, the new Riven isn’t a carbon copy of the original. There are new puzzles, new locations, and new pieces of lore alongside structural changes to make the world more narratively consistent. And this time, it’ll be fully traversable in real-time 3D instead of an interconnected series of 4,000 still images and quick time events.

“We looked at the backstory that gave rise to the world of Riven and the characters that inhabited it,” Vander Wende says. “We found discrepancies and corrected those and embellished things that needed to be filled in.”

I raise my eyebrows. Miller notices. “This is a dangerous question, but when you heard we were remaking Riven, what kinds of things did you hope we’d do?” he asks me.

I think about it for a few seconds. I tell him all the parts of the world I wanted to explore more, as well as the two additional worlds we only glimpsed in the original game. I wince, worrying I’ve just described an impossibly grand vision for the new Riven.

But Miller smiles. “So far? Check, check, check, check.”

Rewriting A Memory

Rewriting A Memory

“Was there always a stairwell over here?”

I’m exploring Book Assembly Island, also known as Crater Island or Boiler Island. I can hear the turquoise water lapping against the shore of its volcanic caldera and the wind pouring over the cliffs above me. The sky is the same blue I remember from my childhood, but now I can walk anywhere and look in any direction.

Seven or eight “Cyantists,” including Miller and Vander Wende, are sitting behind me, watching me play their new version of Riven.

Hannah Gamiel, Cyan’s development director and one of the two people who will lead it when Miller retires, informs me that there was not, in fact, always a stairwell over here. I descend into a dark cave, where an entirely new location presents a new series of puzzles, as well as new insights into the world.

Within seconds, I’m lost. “Always follow the pipes,” Gamiel says, sitting to my right. “Our games should have been called Follow the Pipes 1 and Follow the Pipes 2.”

Gamiel first played Riven when she was 4 years old, sitting in her mother’s lap. “I was the designated disc-swapper,” she says. The original game was split across five separate CD-ROM discs, one for each island. Gamiel’s mother, Robin, would later meet and marry Rand Miller.

Gamiel started working at Cyan in 2013, first in the QA department and then as a programmer. “Those were super lean years,” she says of the time before Obduction, the company’s Kickstarter comeback in 2016.

Later, elsewhere on the same island, I break into a regal laboratory built by Gehn – Atrus’s father, a world-conqueror with a god complex who’s been trapped on Riven for decades – only to discover that the interior has completely changed compared to the original game.

“One of the first things I did when I came back was write a rough outline of Gehn’s 30 years on Riven, which we had never done before,” Vander Wende says. “Once I did that, it was easier to make decisions [about what to change or add].”

After a white-knuckle ride on Gehn’s magnetic levitation tram, I reach the other island Cyan made available during my demo, where Gehn spied on the Rivenese people from a Gothic underwater stronghold. On the surface of the island, one of the structures I remember is missing completely, and there are new puzzles to solve, but Miller assures me the other islands hold even bigger – and wilder – surprises.

“What do you think,” Miller asks me. “You’re the first person to see any of this outside the company.”

I’m stunned. “In some ways, it feels identical to my memory of Riven,” I say. “But in other ways, it’s like I’m playing it for the first time because there are new places and new things I don’t understand.”

Vander Wende frowns. “All I can see are the mistakes,” he says but laughs along with everyone else.

Technical Difficulties

Technical Difficulties

“It’s a puzzle,” Miller says.

A few hours later, we aren’t in Riven anymore. We’re in the Cyan parking lot, and I can’t figure out how to open the passenger door on Miller’s Tesla Model Y. Vander Wende can’t figure it out either, and I think Miller, who is probably one of the most famous puzzle designers in America alongside Will Shortz and that guy who buried a treasure chest in the Rocky Mountains, is sadistically enjoying our confusion.

Once we solve the puzzle (I couldn’t tell you how for the life of me now), Miller drives us through the Douglas fir forests north of Spokane to a restaurant for lunch, where I get to know Cyan’s creative director, Eric A. Anderson, the other person who will lead the company alongside Gamiel after Miller retires.

“I stumbled on Cyan when I was in art school collecting issues of Cinefex magazine,” Anderson tells me. Now in his 40s, he still has the barely bottled energy of a Cyan fan whose dreams have come true. “There was a help-wanted ad in the back that said something like, ‘We’re making Myst II, and we need 3D artists.’” Anderson emailed Cyan asking if it hired college interns, but fate wouldn’t bring him to Spokane until the year 2000 when Miller was spearheading the ambitious, aforementioned MMORPG.

Decades later, in the early days of the Riven remake, Anderson and Gamiel thought they might be able to reuse some of the original game’s 3D models, even though most of them had been lost to the tech-death of SGI workstations, the same now-defunct computers that Industrial Light & Magic used to make Jurassic Park. But when they finally managed to locate and open a single file from the ’90s, it was too low-resolution, forcing them to recreate every inch of the islands from scratch in Unreal Engine 4.

Cyan also met with a grassroots team of Riven fans called the Starry Expanse, which had been painstakingly translating the game’s old models into its own version of a 3D Riven for more than 13 years. “We referenced some of their assets for measurements, but they were replicating the old Riven,” Anderson says. “Once Richard [Vander Wende] came back, we knew things were going to change, so it was easier to just build everything ourselves.”

One of the biggest technical challenges for Anderson and Gamiel has been bringing Riven’s characters back to life. The original game featured live-action video performances by several actors, including Rand Miller as Atrus, Sheila Goold and Regina Altay as his wife Catherine, and Royal Shakespeare Company alumnus John Keston as his father Gehn.

But it’s literally impossible to graft a 2D video from 1997 into a real-time, high-resolution 3D environment. Cyan’s previous remake, 2021’s award-winning VR and PC version of Myst, featured computer-generated characters in lieu of the original live-action performances. “It was… an experiment,” Miller laughs, but for the new Riven, Cyan hired a full-time animation lead, Autumn Palfenier, to raise the uncanny valley.

“For Gehn, we tried analyzing the [old] video and tracking certain features, but the resolution was so low, and it’s not even a full shot, so it just wasn’t doable,” Anderson says. Instead, they’ve been filming performances in Cyan’s basement using motion-capture technology.

“I can say on the record that this is a union production with SAG-AFTRA,” Gamiel says, referring to the same labor guild that represents Hollywood actors. “We wanted to get some incredible talent into this game.”

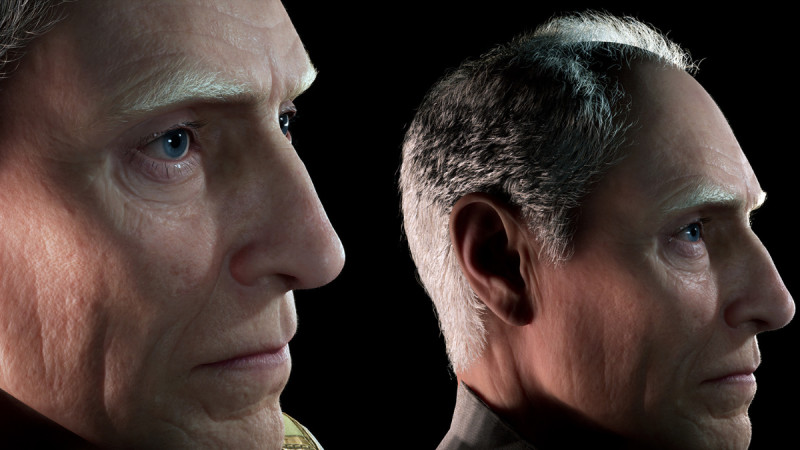

She won’t tell me who’s playing who but does confirm that Miller will return as Atrus and that the studio managed to salvage an old audio recording of John Keston, who died from COVID-19 complications in February 2022 at the age of 97. “We had an actor study John’s performance and then do it in sync with the original audio, so we got Gehn’s full body,” Anderson says. They show me a work-in-progress close-up of Gehn’s face, which exceeds my expectations.

For Gamiel, working with professional actors has been the most rewarding part of the project. “When I watched some of these performances, I was shook. They brought us to tears. People are going to be impressed.”

The Ending Has Not Yet Been Written

The Ending Has Not Yet Been Written

Back at Cyan’s headquarters, I try to get one more surprise on the record before leaving Spo‑ kane behind.

“Can you confirm a release year for Riven?” I ask.

Miller, Gamiel, and Anderson look at each other and make several faces. “It’s coming out sooner than people might think,” Gamiel says. They also can’t confirm or deny (yet) that there are any plans for a VR version, only that it’ll be available for PCs.

“After Riven, will we revisit the D’ni universe in a future Cyan game?” I ask, referring to the fictional civilization responsible for Myst and Riven’s “linking book” technology, of which Gehn and Atrus are practicing descendants.

“100%,” Anderson and Gamiel say in unison. “Star Wars figured out how to tell more than just the story of the Skywalker family, and we’re trying to do the same thing,” Anderson says. “There are more stories to tell in the D’ni universe that aren’t directly about Atrus’s family. There are other characters out there that [our fans] are familiar with, and it would be a shame if we didn’t leverage those to our benefit.”

It’s time for me to go, but I keep thinking about something Vander Wende said the day before. “When Riven came out, most of my friends and family didn’t play because it was too difficult. I just didn’t know whether what we made really meant anything to anyone,” he said.

Days later, back at home in North Carolina, my 7-year-old daughter walks up to my desk while I’m writing this story. She notices an image of the original Riven on my second screen – a dramatic vista of a massive golden dome surrounded by vertical sea stacks.

“Where is that place?” she asks, her eyes wide.

I almost tell her it’s from a video game. I think about playing Myst with my dad and playing Riven with my brother. I think about how happy my mom was when I told her I was flying out to Spokane. I think about Vander Wende, Miller, Gamiel, and Anderson and what it means for art to make an impact on people.

“I’ll take you there soon,” I say.

This article originally appeared in Issue 362 of Game Informer