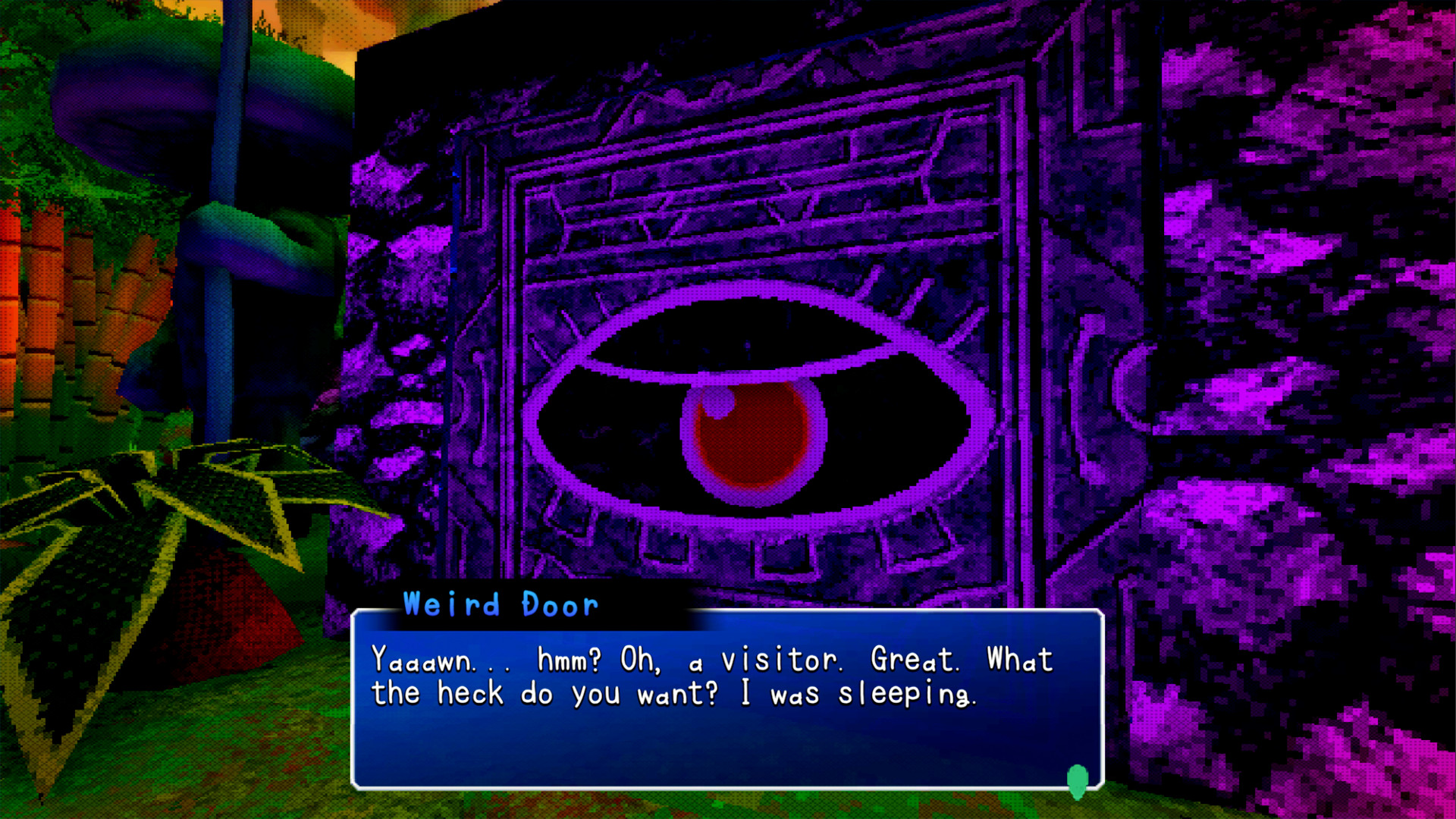

Itch has been unseasonably spooky for some time. If you’ve taken a cursory glance at the indie storefront’s homepage in the past few years, you’ll have noticed row after row of not just horror games, but a very specific kind of horror game. From low resolutions to wobbly vertices and a healthy dose of thick black fog, there’s a distinctly PlayStation 1 vibe to these indie spookers.

See, on Itch, it’s Halloween 1998 every single day.

Screen’s haunted

Haunted PS1 didn’t start this trend. Indie developers like Kitty Horrorshow, Paratopic developers Arbitrary Metric, and even throwback shooters like Dusk were already well aware of the power of early 3D graphics to unnerve and unsettle. But Haunted PS1 has certainly become the pillar for this movement in recent years—starting from a small Discord server for devs working in similar styles to something so vast and fast-moving that even HPS1 creator Breogán Hackett has trouble keeping up.

I spoke to Hackett for Wireframe back in 2018, when HPS1 was still a fledgeling movement, to ask why early 3D horror was becoming so popular. They told me that it’s that era’s technical uncertainty that drew their attention—a period of experimentation and limitation that led to those earliest 3D worlds always feeling just a little bit off.

“Everything is a little less well-defined, so it’s hard to tell exactly what you’re looking at,” they explained. “Especially PlayStation graphics, where there are jittery vertices and the textures are warping—it feels like the game can be falling apart at times. It’s really unsettling and unnerving.”

But since Haunted PS1 began as a small gathering of developers back in March 2018, the movement has absolutely exploded—going from the odd monthly jam to a constant flood of wobbly, lo-fi spooks. So three years later, I caught up with Hackett to ask what exactly is going on with Haunted PS1, and why ’90s frights have proven to be so enduring.

“The obvious answer is that it’s a lot easier to pull off a stylistically consistent 3D game with graphics that look straight out of 1998 than it is to pull that off for something that looks modern,” Hackett tells me. “I guess if our community was the Haunted PS5 there’d be maybe 2 members and 0 releases in the same time as the HPS1 has seen over a thousand members and hundreds of releases.

“That aside, though, the real core of what makes the style so magic to me is the combination of nostalgia and abstraction. This is a powerful combination for creating a wide variety of atmospheres, from the dreamlike to the terrifying.”

“If our community was the Haunted PS5 there’d be maybe 2 members and 0 releases in the same time.”

This tracks hard with my own brief experiments in the form. I’d been gearing up to take part in one of HPS1’s earliest jams with a short game called GIGASTRUCTURE—and while that ultimately never came to anything, it was shocking the speed at which even a lapsed artist like myself could cook up textures and props, throwing them into blocky Unity scenes with low-res cameras to create eerie (and more importantly, convincingly old-school) spaces.

As Haunted PS1 grew, it also spread its low-resolution claws beyond horror’s genre boundaries. Hackett shouts out Toree 3D, which despite sporting the Haunted PS1 branding is a saccharine 3D mascot platform more in line with Sonic Adventure or Gex; or Hypnagogia 無限の夢 Boundless Dreams, a surrealist dreamscape that feels more like an obscure Dreamcast game bought on import from the back of a zine.

But the retro horror movement didn’t just grow. It exploded, and there are now countless games sporting early 3D scares. Looking like the original Resident Evil isn’t enough to stand out by itself, and it can be hard to figure out what’s worth checking out among a sea of jittery vertices.

Haunted PS1 has put together a great many community initiatives to highlight the best and scariest the movement has to offer. Semi-regular Demo Discs compile a selection of boutique scares behind a wonderfully grimy, period-appropriate demo disc frontend. They’re not the only ones doing it, either—indie horror publisher Dread XP frequently launches Dread X Collections including games like the morbid Squirrel Stapler and gruesome WarioWare-esque minigame compilation SpookWare.

“I think there’s a lot of developers assuming the art style might do a lot of the work for them.”

Even so, Hackett stresses discoverability remains a problem for all indies, and the retro horror scene is no exception. But not only is it not enough to rely on the novelty of looking like an old game to shift copies—Hackett reckons the culture that’s grown around retro horror “can’t or won’t” pay for commercial games.

“Looking at big franchises, it seems the audience for horror games in general does skew quite young on average, so what does well in the realm of free horror games is not necessarily what does well in commercial projects. I think there’s a lot of developers assuming the art style might do a lot of the work for them.

“I’d like to hope that interesting work isn’t falling through the cracks just because of its presentation but I know this has been happening in games for a long time already.”

Alt-horror

There’s also, as ever, the question of what comes next. It’s been three years since I first spoke to Hackett, and the early 3D aesthetic has well and truly settled in. But will indies continue moving forwards, through the smeared realms of the PS2 and onwards into the bloom-stained lights of Xbox 360-era games?

Hackett hopes not. The early 00s were a time where studios and budgets escalated massively in scale to chase higher fidelity worlds, and Hackett believes that rather than following this path, retro horror devs will find different directions to take their works, building entirely new styles from existing limitations. It’s already happening, too—adherence to the original PlayStation’s capabilities has never been a hard rule.

“A good low rez horror game after all plays off the gap between perception and presentation. PS1 style art is certainly not the only way to achieve that.”

“The prevailing style of indie games is, in a way, now becoming disconnected from the concept of hardware limitations. Most HPS1 developers have been doing things that would have been impossible on older hardware since the inception of the style. Modern hardware affords us opportunities to subvert and surpass expectations we build into our game’s visuals and as we do this more we discover interesting new ways to present our work.”

After all, that’s always been the best part about retro horror games. Not the absolute purism of reliving the 90s, but the jarring anachronism that comes from seeing Bloodborne reimagined as a PlayStation 1 game, or an online shooter server lobby playing off a VHS screen. It’s a movement that’s best when it takes the uncertainty of early 3D visuals and unpredictability of the industry at the time, and pulls those threads in terrifying, strange and surreal new directions.

“A good low rez horror game after all plays off the gap between perception and presentation. PS1 style art is certainly not the only way to achieve that, so let’s explore what else we can do!”