Sitting near the feet of the chalky white cliffs so famous of the British South Coast lies East Sussex College, in Lewes. Last year, the college announced the addition of esports to its curriculum by offering the BTEC Level 3 National Diploma in Esports, a practical learning-focused qualification for high school-aged students in the UK.

Lewes is an old, deeply historic town. Traditional, independent, old-fashioned — the kind of place you might quicker expect to find Latin on timetables than esports.

In places like these, both in England and across the world, esports has long been on the losing end of mainstream opinion. It has had to battle the tides of entrenched negative stereotypes about gaming and gamers, and the ‘evils’ they purportedly play on today’s youth.

The arrival of the BTEC Esports qualification to the college, then, is a testament to how far esports has come in recent years. The skills-focused course covers everything from esports business and marketing to coaching and video production, and is now being taught at 70 institutions across the UK.

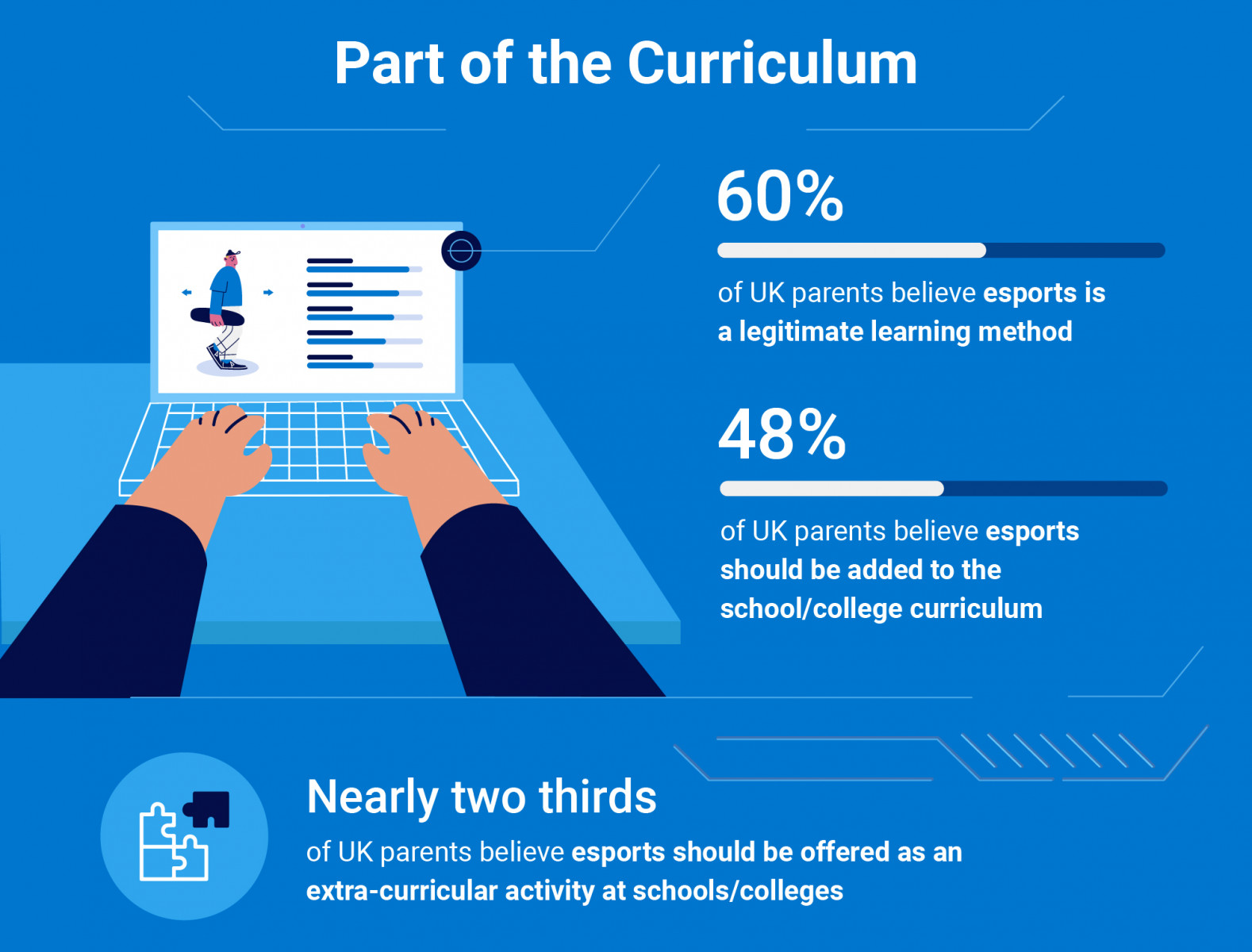

How did we get from there to here — from mainstream vitriol to esports courses in schools? Perceptions about esports are slowly changing, studies have shown. A recent report commissioned by Dell Technologies and Intel found that parents and financial decision-makers in education are optimistic about the role of esports in education.

The results of the study show that 69 percent of UK parents believe esports allows their children to develop skills that they might not get through traditional education methods. Of those, 54 percent say esports gives children more confidence — with teamwork, problem-solving and technological skills coming out as the other top skills parents believe children can develop through esports.

RELATED: LDN UTD and The Strive Group launch UTD EDN education initiative

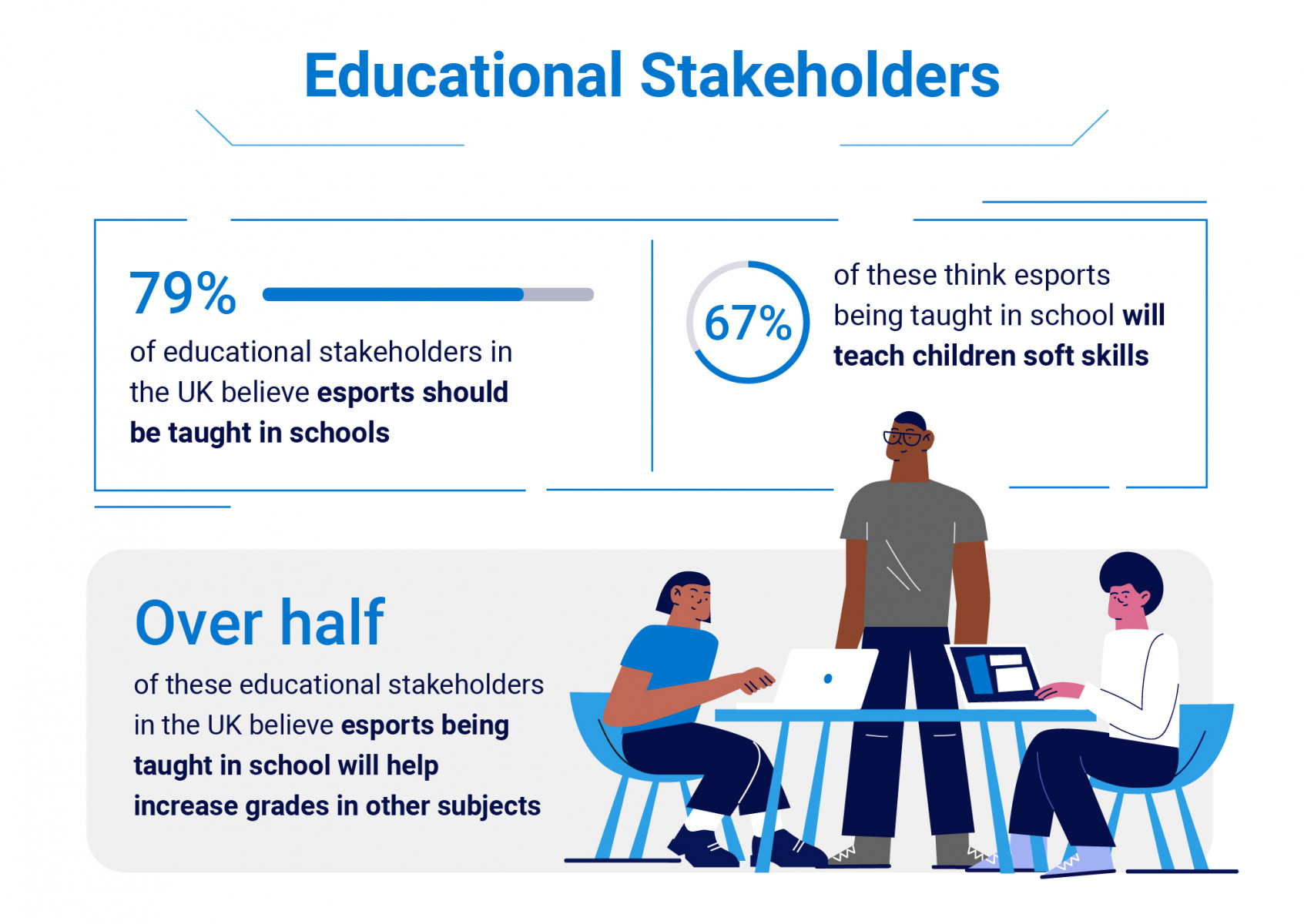

Moreover, the report found that 79 percent of financial decision-makers believe esports should be taught in schools, and almost half of parents surveyed think esports should be added to school curriculums — a sure step forward in overcoming dogged stereotypes.

However, despite parental enthusiasm, esports retains somewhat of a chequered history in education. When the first university degree in esports arrived in the UK in 2018, it attracted national headlines and cautious optimism as a step forward in esports’ quest for mainstream legitimacy. But the degree subsequently met widespread criticism over course content and teaching. And it’s far from the only controversial, poorly-received attempt at an esports qualification.

The Esports BTEC, meanwhile, has had an ostensibly successful rollout. Almost 200 institutions in the UK and globally are approved to teach the course. 70 centres actively teach it to over 2000 students across the UK, a huge jump from the initial 15 institutions in 2020, the qualification’s inaugural year.

The BTEC has perhaps managed to succeed where predecessors failed because it approaches esports differently from an educational standpoint.

“There’s no such thing as teaching esports, just as there’s no such thing as teaching sports, because it’s so vast and so big,” explained Gary Tibbett, Education Manager at the British Esports Association, which helps run the BTEC. “What we do is teach transferable skills that allow you to learn while you’re doing something you love.”

One of the major criticisms of existing efforts to educationalise esports is that the sector is too wide and too general to be taught in one course. Key to the success of the BTEC, Tibbett explained, is using esports as a medium to teach other skills, rather than teaching ‘esports’ as a subject.

“It’s not about teaching esports in the narrowest sense,” Tibbett told Esports Insider. “It’s about using esports as the hook, the passion, the trojan horse, to sneak in there — and then what you do is you unload everything that you actually want to teach them on top of it,” Tibbett laughed, only half joking.

Much of the value of esports’ place in education comes from its role as a conduit for valuable skills that students can utilise both inside and outside the sector.

Esports can help drive learner engagement and outcomes, while imparting valuable digital and STEAM skills to prepare students for future career paths, argued Brian Horsburgh, Education Sales Director for Dell Technologies, during a press event announcing the survey results.

Horsburgh said esports comes equipped with transferable soft skills like teamwork, public speaking and communication strategies — assets one hopes to develop from school regardless of subject choice.

But at the most fundamental level, it’s an excuse to turn up, he explained. Since esports is their passion, students keep coming back because they’re doing what they love — meaning attendance implicitly increases and dropout rates decrease.

“We’ve seen attendance and retention on our programme double just purely based on the fact that we’ve introduced esports into our curriculum,” said Camilla Maurice, Curriculum Manager at MidKent College, at the press event.

“If we’re able to provide something that is different from the norm, that’s innovative, that’s that’s fresh for them to engage in, that they love, they’re going to rock up every day and they’re going to enjoy being in the classroom.”

While parents are opening up to the idea of esports in schools, only 32 percent would be happy for their child to have a career in esports, according to the Dell & Intel study. The study points to the fact that parents may be unaware of the breadth of career options available — though reliable career opportunities have always been a concern for impassioned youths eager to enter full-time jobs in the industry.

The skills-focused approach of the Esports BTEC looks to avoid this problem. Unlike higher education courses laser-focused on specific esports skills or knowledge — which some see as tying students into a path-dependency in esports — the BTEC is designed to offer more generalisable skills.

“Pearson has designed these qualifications to support the development of broader transferable skills that are vital to succeeding in the future workplace, as well as esports-specific skills,” Donna Ford-Clarke, a Director of Vocational Qualifications & Training for Pearson, told Esports Insider. “Learners also have opportunities to develop a range of skills from other disciplines, such as psychology, games design, marketing or computer networking.”

Ford-Clarke said learners develop interdisciplinary and personal skills, from entrepreneurship to marketing to business management. These can be utilised across growth sectors and open up choices for their next steps, whether that path leads to esports or elsewhere.

Students do not have to go into esports just because they did the Esports BTEC, Tibbett said. It’s not meant to simply be a feeder system for the esports industry — and that’s what makes it so valuable.

RELATED: IESF partners with NASEF and appoints Chair of World Esports Education Commission

“This qualification isn’t just to get a job or internship or university spot for esports,” he continued. “We’re not teaching esports as the core, with a bit of production on the side — it’s the other way around.”

This more versatile form of incorporating esports into education doesn’t tie students down to a specific career in the still-young-still-risky esports industry. It doesn’t limit options to a field where fairly paid job positions are highly competitive even amongst the most qualified candidates — right down to entry-level positions.

Instead, some 2000 students are looking to graduate with a qualification that treats esports more as a prism than a subject. As esports becomes a hotter and hotter commodity in the world of education, these students aren’t learning to play — they’re playing to learn.