I never imagined I would be writing this when everyone first got word of a new Need for Speed game in development. Initially revealed in the summer of 2020 with a shot of two cars, said game would not get an official title until October of this year.

Months after leaks and rumours told us a lot of what EA wasn’t interested in sharing itself, and Need for Speed Unbound was revealed, with all excitement reserved for racing games that aren’t Forza.

I find it hard to believe that anyone could say they were truly looking forward to Unbound, beyond the general excitement one might have for a new major release. I have long since given up hope that Need for Speed would even so much as plot a return to form, and everyone I know has either moved on to more realistic racers – or has stuck with Forza for their driving fix.

EA’s actions, too, reinforced a narrative that not even Unbound’s publisher has any hopes for it, deftly demonstrating a lack of confidence in the game… even before it was revealed.

The game wasn’t shown to press – or even easily excitable influencers – at any point. The short window between announcement and release, especially given the early December date, painted it as an unwanted child; something the company needed to put out there sooner rather than later to cut its losses and move on.

Intentionally or not, EA has sort of carved that dire niche for itself. Mass Effect Andromeda, Anthem, and more recently Battlefield 2042 were all knowingly put out in unacceptable shape. Some were lucky to get support afterwards, while most got the mercy bullet instead.

All of that really makes the quality of Need for Speed Unbound all the more surprising. The fact that I spent roughly 10 hours with it (and look forward to playing more rather than uninstalling) should really tell you everything you need to know. Starting with Rivals in 2013, all the way until 2019’s Heat – there isn’t one Need for Speed game in that period I enjoyed.

The handling always felt off, and being forced to compete with Forza filled those games with pointless, hollow open worlds that failed to justify their existence. EA’s awful Frostbite engine mandate was the killing blow; an engine made for shooters that everyone else had to struggle with just to get acceptable results affected Need for Speed most of all.

Unbound is the first Need for Speed in years with an identity. It borrows from Forza, sure, but only where it makes sense for what it’s trying to be. It’s set in an open world, there are collectibles you can grab, speed zones, and drift zones to run through.

But it also has the – Criterion classic – billboards for you to smash through, and the level design of a game made to be a playground for racing: wide streets, destructible objects, smoothed off entries, and shortcuts around every corner to help you shave a few precious seconds off your route (or simply hide in when you want to avoid the cops).

Cop chases, of course, have always been one of Need for Speed’s most compelling mechanics. But just like Criterion took a page or two from Forza, it also learned from the series’ own past successes. As much as I tried, I couldn’t get into Need for Speed Heat, but even I can’t deny the brilliance of its night/day split that rewarded you for taking risks, and added stakes to exploring its bland open world.

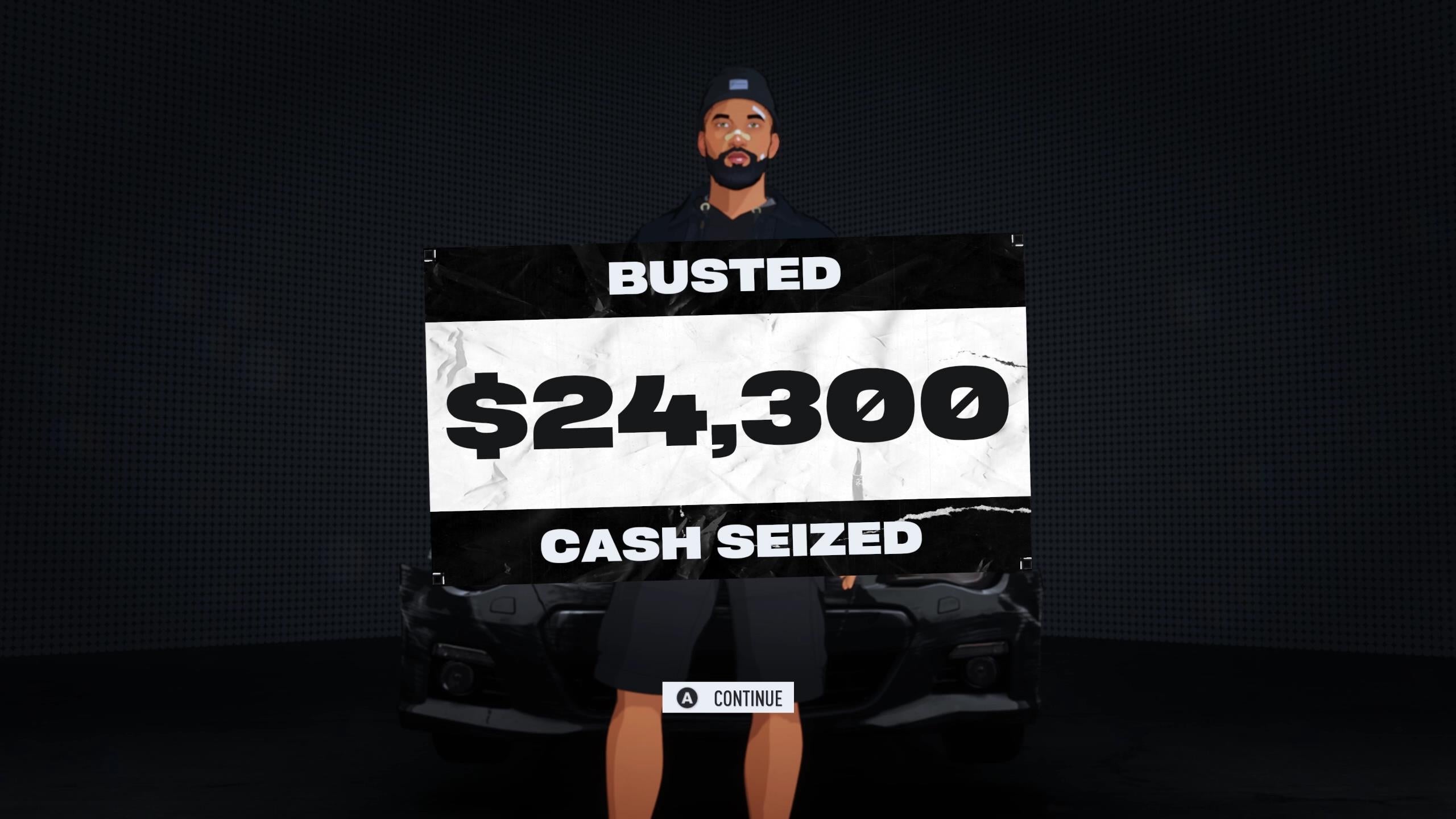

That mechanic has evolved in Unbound. Every activity you take part in raises your heat level making it more dangerous for you as you travel between them, and in the races themselves. The heat doesn’t reset until the next day, meaning hiding at a nearby garage or safehouse only lets you bank your current earnings, and not escape entirely scot-free.

On your next outing, you have two choices: you could skip that entire portion of the day and head back to the garage, ending the day and resetting your heat level. But doing so means you’ll miss out on the day/night’s activities, and any potential earnings you could’ve made. It also means you’ll be less likely to be able to compete in that week’s big tournament, which requires cars for each class to enter.

Every time you leave the garage each day is exciting, and the game will subtly push you to take risks and make bigger bets. Most of the races themselves have a buy-in, and you can even make side bets for more cash.

It’s a satisfying gameplay loop, clearly full of touches that could only come from a developer who knows racing games. But perhaps its most compelling triumph is in finding a reason for Need for Speed to exist.

Unbound shows a path away from Forza’s sticky racing lines, free rewinds, fabricated positivity and car-collecting hunger. This is a game where the races themselves matter, where mistakes are costly. It’s a game that wants you to spend time with a single car, to know its intricacies and upgrade it in a way that makes sense for you, not treat all cars as stepping stones.

Unbound is a not just a reminder of when Need for Speed was good: it’s an argument for why it should remain.