It happens again for the fifth time since I began Starfield: During a conversation with an NPC, my companion, trapped by an airlock or some obscure gnarl in the level architecture, chimes in from a completely different room. During his lines, the camera swivels in the direction of wherever he is on the map. The space where his head usually appears is instead occupied by a blank, expressionless wall.

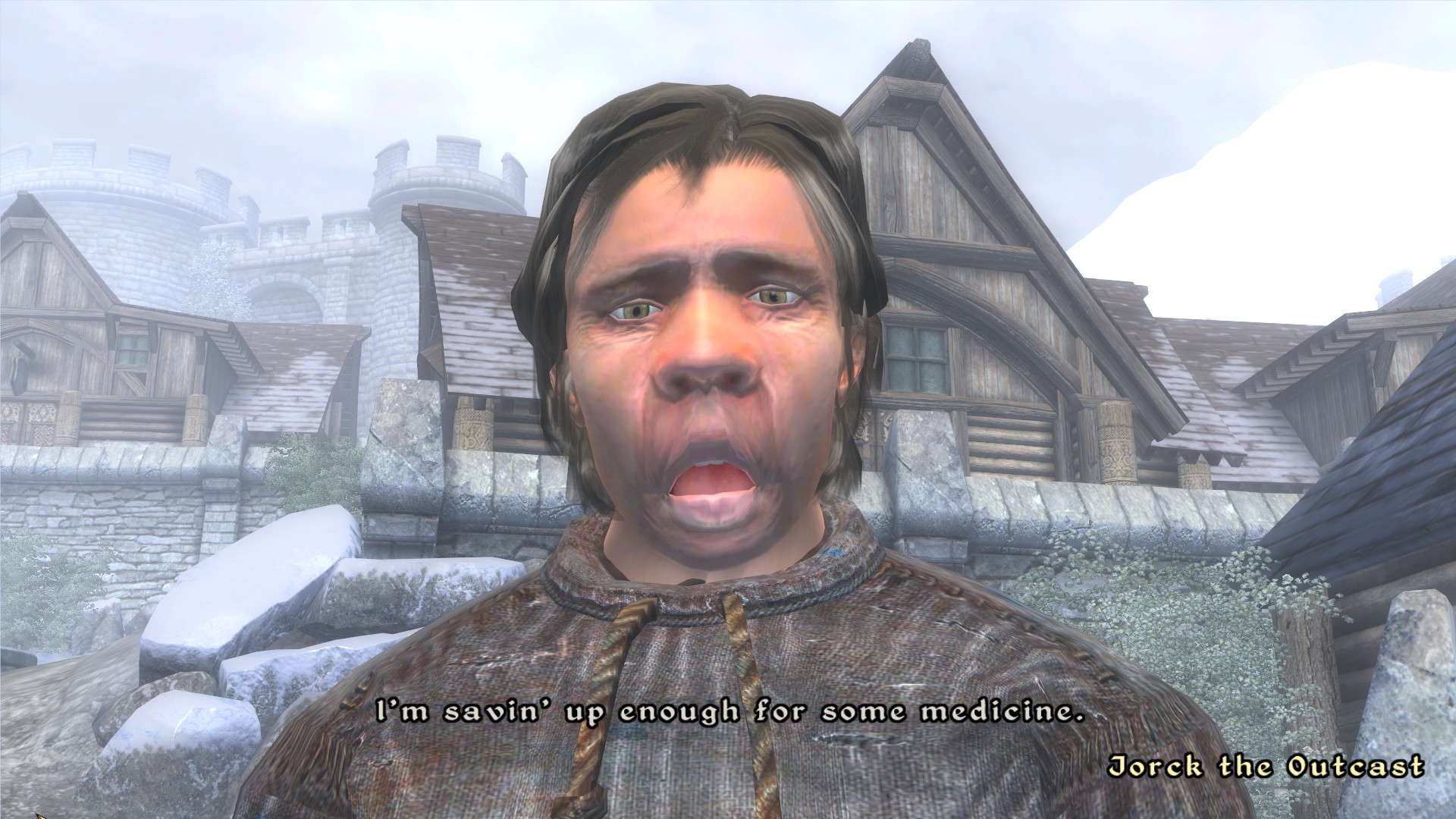

For anyone who has spent hundreds of hours snout-deep in any of Bethesda’s open-world buffets (myself included), this phenomenon is nothing new. Ever since The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, Bethesda’s games have become heavily associated with jank—NPC behavior that produces unintended consequences, defies realism, or otherwise disrupts the flow of the game.

Starfield is no exception. Pass by too many NPCs at once and you might hear the same canned line of dialogue delivered by different, overlapping voice actors. Committing violence anywhere in an indoor urban environment may trigger audio samples of crowd panic even in the absence of other visible NPCs. Failing to pickpocket a cube of synthetic meat from a stranger causes every NPC within a mile of your character to howl and flee in terror. NPCs are liable to begin floating towards the sky without warning, twist their necks at impossible angles, and wander into conversations like lost children.

For some, this is evidence that Starfield has failed to live up to its expectations. The post-release discourse has surfaced numerous unfavorable comparisons to Cyberpunk 2077, No Man’s Sky, and Mass Effect. At the same time, jank has come to define our collective remembrance of Bethesda’s games, becoming something of a comforting presence for anyone who knows parts of Tamriel like the back of their short-haired Khaajit hand.

Jank isn’t a bad thing. Rather than detracting from Bethesda games, jank elevates them, injecting spontaneity and humor into worlds that might otherwise feel barren and lifeless.

An abridged history of NPC jank in Bethesda games

Bethesda has always strived to achieve a feeling of immense scale, leaning on procedural generation in order to populate the towns and dungeons of both 1994’s Arena and 1996’s Daggerfall. 2002’s Morrowind was the first in the series to ditch procedural generation in favor of hand-crafted assets and environments, codifying many of the conventions that would come to define Bethesda’s approach to open-world design.

2006’s Oblivion and 2008’s Fallout 3 introduced full voice acting and AI that allowed NPCs to engage each other in autonomous conversation. You’d wade through cornfields of loot until an NPC emerged from the glade, offering to give you a sidequest or slit your throat for your belongings.

During this generation of Bethesda games, jank felt like a symptom of the studio’s undying open-world aspirations. The procedurally generated, text-based NPC dialogue of Arena and Daggerfall was less vulnerable to awkward pacing, but now that every NPC could talk, players were much more likely to experience jarring tonal shifts as characters reacted to their sudden actions. More detailed NPC models, animations, and behaviors meant a higher risk of witnessing unrealistic collisions between characters and their environment.

I not only overlooked moments of jank—I celebrated them

But I didn’t mind back then. I was so enamored with Fallout 3’s spectacularly bloody V.A.T.S. system that I not only overlooked moments of jank—I celebrated them, relishing every instance a raider’s disembodied spine would refuse the call of gravity, nailed to an invisible wall in midair. I howled with joy whenever one of Oblivion’s guards would pursue me for countless in-game hours only to run, with baby-faced innocence, off of a cliff.

This was Bethesda’s open-world entropy at work, punctuating journeys across Fallout 3’s Wasteland and Oblivion’s Cyrodiil with surreal and unpredictable NPC encounters. The stilted delivery of the games’ voice casts only enhanced these moments. Without jank, actions like pickpocketing or committing random acts of violence might have felt more dull or straightforward.

I wasn’t alone in finding charm in these quirks. This 2007 YouTube sketch is one of the earliest videos to juxtapose Oblivion’s NPC conversations with real life, highlighting the bizarre logic that pervades in-game interactions. Though Oblivion and Fallout 3 occasionally come apart at the seams, this was once considered a small price to pay for access to the vast, open sandboxes Bethesda had created.

Bethesda, please never change

As hardware has evolved so has the demand for seamlessly realistic worlds. Cyberpunk 2077’s notoriously disastrous launch was met with countless criticisms regarding bizarre oddities like nude, T-posing motorcyclists. 2021’s “Definitive Edition” of the GTA trilogy was also given the fail compilation treatment after its buggy release. In the age of ray-tracing, any big-budget simulation of real life invites relentless scrutiny about the ways in which NPCs might disrupt a player’s sense of “immersion.”

It’s the jank that makes Starfield unmistakably Bethesda

Meanwhile, it’s been 17 years since Oblivion, 12 since Skyrim, and seven since Fallout 4. Starfield promises us an experience that previous generations of hardware couldn’t deliver, encompassing spaceship customization, dogfighting, piracy, and interplanetary colonization. Occasionally, it delivers, inspiring awe with its glimpses of lush alien vistas, the depths of its faction-oriented questlines, and yes, the sheer scale of its abyssal vision of outer space.

Yet it’s the jank that makes Starfield unmistakably Bethesda. It warms my heart when I approach an NPC and they address me only to reveal they don’t have a face, or when UC Security proves they’re just as jumpy and prone to sudden acts of brutality as Oblivion’s Imperial Guard. When Starfield’s gameplay loop—fast traveling to distant solar systems, clearing out nests of space bandits, and relieving locker after locker of their aging sandwiches—begins to feel like a slog, it’s jank that lifts my spirits again.