In this piece, Hannes Hase, a Data Scientist at Bayes Esports, breaks down how League of Legends balance patches impact the meta and data surrounding a match.

Disclaimer: This is a sponsored piece from Bayes Esports

In a game as complex as League of Legends, keeping champion strength, item stats and general interactions in balance are key to keep the community around it happy. The struggle here is that whenever new elements are introduced into the game, it is hard to fully estimate their impact, leading to a necessary readjustment afterwards. For this, Riot releases balancing patches every few weeks, trying to amend unwanted and unexpected over-tuned aspects of the game.

As soon as a new patch is announced, players all around the world start looking for new ways of exploiting the potential consequences of the introduced changes. This leads to changes in the meta. Meta, or ‘most effective tactics available’, is a term recurrently used in the gaming world to describe the go-to picks or strategies at a given time. It is not mandatory to follow, and players have had success with off-meta strategies, yet following the meta usually is the safest path to victory.

Meta is fluid and depends on several in-game factors like items, changes to the map, new champions and adjustments to neutral objectives. It is the approach and understanding the player base has of the game at a given space and time. Thus, when following international tournaments, we can see how meta shifts as the tournament progresses and how drafted team compositions are completely different towards the finals when compared to play-in stages.

The most drastic changes are usually introduced by Riot at the start of each year and season. Recent reworks brought the introduction of Elemental Dragons and the Rift Herald, a complete redesign of the jungle or the creation of role-specific items. The current season 11 began with a very ambitious overhaul of the item system, which largely impacted the game and meta.

For amateur League of Legends players everywhere, understanding the meta helps them to climb the ranks in Solo Queue. For professional players, finding and understanding the meta leads to more victories and maybe even championship titles. At Bayes Esports, we need to reach an understanding of the meta to stay ahead of the curve and be able to always deliver the best product possible to our customers. Here is a peek into how we analyse the impact the item system rework had on the understanding of the game across major regions, and how this affected the preferences of professional teams.

For this purpose, back in February, we built a dataset from all Master+ Solo Queue matches from the Riot API for patch 11.1 for the three most relevant regions for the competitive scene: Europe West (EUW), North America (NA) and Korea (KR). (Note: The Riot API does not give access to the Chinese Super Server, so we cannot include this region in this article.)

The intention of this article is to highlight how different regions develop unique play styles and to showcase the reason why a game patch has an impact on a region’s tournament performance — not to analyse current game strategies.

Since this study was conducted we have seen multiple meta-shifts. Recently, jungle changes have given champions like Morgana and Rumble an unexpected priority and Lee Sin has made his comeback to the Rift, but this time as a laner.

Those of you closely following competitive League of Legends, will realise with this article how quickly in-game analysis becomes outdated.

Regional differences in Solo Queue play

To study the main differences of Master+ Solo Queue play across regions, we look into two parameters — champion popularity and champion success. We call champion popularity the number of games where a particular champion was either picked or banned over the total number of games from that region. As a measure of that champion’s success in that region, we use its win rate. To avoid niche picks, we do not consider champions whose joint pick and ban rate are under five percent.

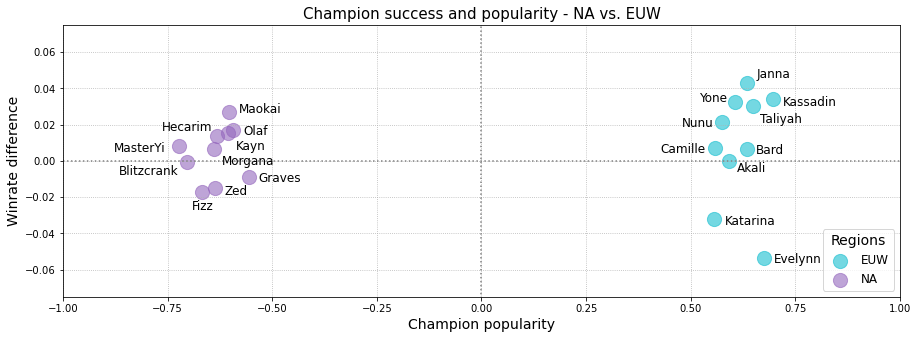

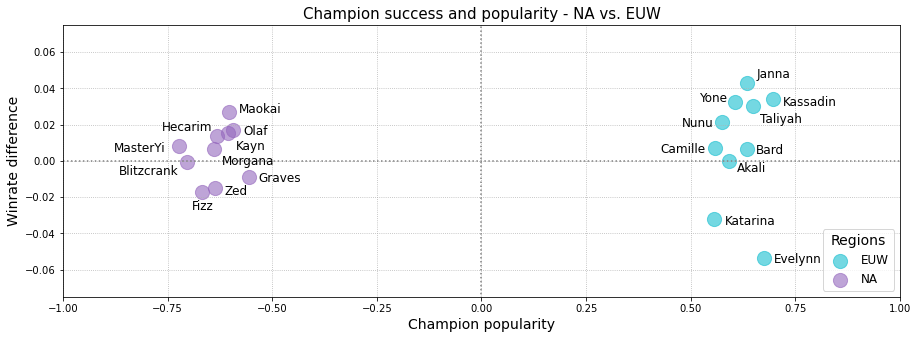

We chose the ten champions for each region that presented the most considerable popularity difference in patch 11.1 for each pair of regions and plotted it in the figures below. Each plot shows the difference between two regions, with the popularity difference on the X-axis the win rate difference and on the Y-axis. When reading the plots, we can say that for example, the champion Khazix was around 85 percent more likely to be picked or banned in Europe than in Korea.

On the same line, we can say that Khazix was more likely to win a game in Europe by slightly more than two percent.

On an overall note, it is interesting that the roles with the highest variance in terms of champion picks were jungle and support. As both these lanes are relevant in making plays happen for the team, it is an initial confirmation that different regions have different approaches to the game.

We see that both EUW and NA had a higher preference for assassins than KR. On the other hand, Korea tended more to like ‘ability power’-based jungle champions and tank supports.

We also find that Korea’s popular champion set repeated itself when comparing it with EUW and NA. From this insight, we can conclude that the Korean playstyle had a very distinct preference when it comes to champion priority.

When looking at the graphs, there appear to be three types of champions. The first type becomes clear when looking at Darius. Darius was more prevalent in NA and EUW than KR, yet he did not appear in the comparison between NA and EUW. This behaviour can be explained by Darius being a strong pick in the meta of western regions, yet not prioritised as highly in KR comparatively speaking. Other champions in a similar situation were Seraphine and Draven.

Hecarim exemplifies the second champion type. This jungle champion appeared to be picked more frequently in EUW than in KR. Yet, when comparing EUW with NA, we find that Hecarim enjoyed even higher priority in NA. This chain implies that Hecarim had a significantly higher priority in NA than KR. We see the same for Taliyah (KR), Evelynn (EUW) or Katarina (EUW).

To describe the third champion type, we look at Pantheon. Pantheon appeared to be prioritised higher in KR than both NA and EUW but did not appear in EUW vs NA. This does not mean that Pantheon was not relevant in EUW and NA, but only that he appeared significantly more in KR during pick and bans. Other champions that fall under this category are Nunu and Yone (EUW).

As already mentioned before, all other preferences from KR repeated themselves compared to EUW and NA. It seems that KR players are less experimental and usually pick champions from a narrower champion pool compared to the other two regions.

We also find champions like Camille, Morgana or Zed, which only appear once across the graphs. This situation indicates no clear overall tendency, but it shows the nuances in meta in different regions.

Lastly, it is essential to comment on high priority champions in patch 11.1, like Kaisa, Jhin, Aatrox or Sett that do not show up in the plots. This does not mean that they were not popular.

In roles like AD carry and top lane, the viable champion pool was very restricted. Consequently, their priority was comparable across regions and the threshold for a local meta shift was higher, leading to less interregional popularity differences on these champions.

Meta in professional League of Legends

In the previous section, we looked into differences in how players approach the game in Solo Queue. Now, to get an idea of how meta is defined in professional League of Legends we contacted Christopher ‘Duffman’ Duff, Head Analyst of G2 Esports, the most successful team for the past few years in western regions.

What is the main difference between Solo Queue and pro-play when it comes to

champion prioritisation?

CD: One of the main differences will be how draft works in Solo Queue vs pro play. In pro play, draft is much more structured. Teams have different priorities on who picks how early, who gets bans for example. In Solo Queue that’s not the case and you generally pick in your given order. This leads to matchups that would never happen in a competitive game as you would either ban them out or you wouldn’t leave yourself in a spot to be counter picked.

From your experience, is there an overlap between the region’s Solo Queue meta and the meta in its professional scene? And if yes, why does this happen?

CD: There is a lot of overlap in terms of champions/items that are fundamentally overtuned/overpowered. When these situations come up, you’ll often see the champion picked and banned in both.

How do you prepare to face these different play styles when going to international tournaments?

CD: When it comes to international events, you mostly try to scout what teams played in their home regions and try to think about how it may adapt and where their play-style interacts with yours. It’s not an exact science because sometimes you have to account for 3-4 different teams and it can be hard to prepare for them all, so I think the main focus is on making yourself most comfortable in your approach while negating ways their play styles can attack yours.

When going to international tournaments, what kind of meta has historically favoured LEC teams?

CD: Historically 1-3-1 split pushing comps where solo lanes want to play on long side-lanes in mid-game favour EU teams. We have seen in 2018 that even when outmatched in bot lane, if you have the right champion pool, you can avoid fighting “stronger” teams on a level playing field by split pushing and this is where Europe has a lot of experience vs other regions.

Champion presence differences in Solo Queue vs. pro play

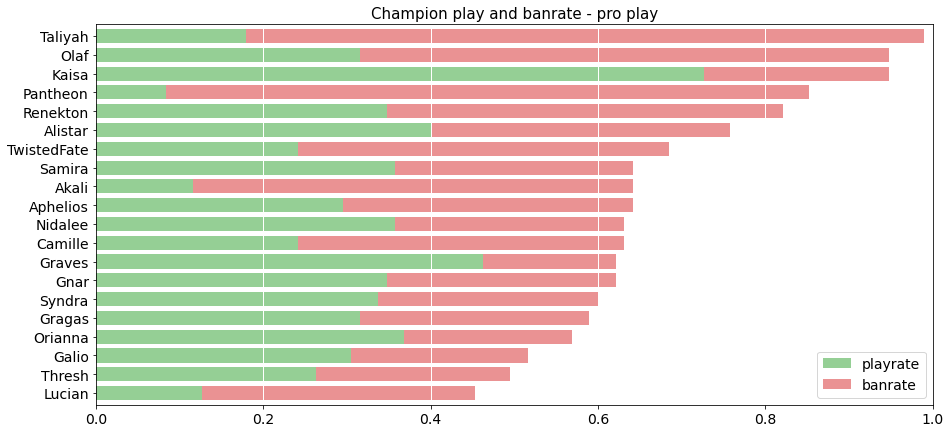

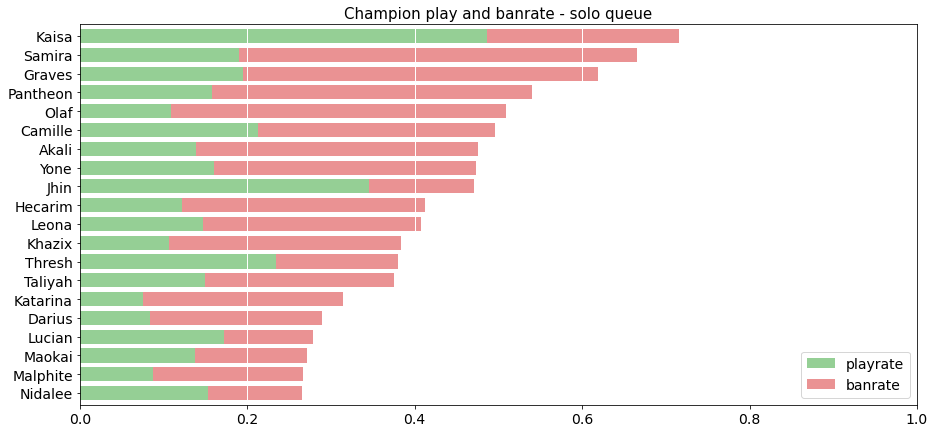

With these insights from the professional analyst scene, we look at the differences between the 20 most present champions in pro-play vs. Master+ Solo Queue games worldwide for patch 11.1.

At a first glance, a few things pop up. First, the difference in the magnitudes of joint pick and ban rate of highly prioritised champions in pro play vs. Solo Queue. Just like Duffman points out, drafting in pro-play has a more coordinated draft phase and it shows.

Another interesting discovery from this comparison is that most of the champions with the highest presence are more likely to be banned than played. This relation hints at over-tuned champions, with little room for counter-play or difficulties in dealing with them if they manage to get ahead in the game. Especially the ban rates of Taliyah, Pantheon, Olaf and Akali in pro-play showcase how these champions could potentially ruin the game plan of one of the teams.

In games where these champions were left open to be played, it is usually because either there were more important bans for the team’s strategy or the team had an answer to that specific pick. In Solo Queue, players usually ban champions depending on what they want to play or what they do not want to play against. Over-tuned champions, like Samira or Yone fell in this last category in patch 11.1.

The champions that had a significantly higher play rate than ban-rate like Kaisa (pro play and Solo Queue) and Jhin (Solo Queue) showcase that players strongly target positions other than AD carries when banning champions. That these two champions were so popular also indicates the current problems in viable champions to be played in the bot lane.

One more thing stands out if we go into which champions appeared only in one of the plots and which repeat themselves. If a champion is present both in pro-play and Solo Queue, it hints at over-tuned stats or item interactions. Among these champions, we encountered the likes of Pantheon, Olaf, Camille or Akali, and those who faced them on Summoners Rift in early 2021 will have experienced the reasons behind their high priority in the patch in question.

It is in the differences where we can appreciate the effects coordinated drafting has on champion priority. When considering champions that showed popularity in Solo Queue games, we see characters like Yone, Darius or Katarina, which had (and still have) the potential of winning games on their own in an uncoordinated setting, yet are vulnerable to targeted counter drafting, rendering them not as impactful in professional games.

Conversely, champions with a huge impact in coordinated team-fights are more likely to appear in pro-play than in Solo Queue, and we can see this in our data. As we would expect, champions such as Gragas, Orianna or Gnar appear more often as their abilities require a level of coordination that is difficult to achieve without efficient communication in the team. On a similar note, we find champions with global abilities like Galio and Twisted Fate. Global abilities are more effective if the whole team is aware of their use, which is why we see these champions prioritised in the professional scene. An extreme case is Taliyah, who has a global ultimate and was popular in both game formats, yet had a significantly higher presence in pro-play, confirming the prioritisation of global abilities.

Conclusions

With the conclusion of MSI, the first half of season 11 has ended. From early 2021, the game has completely changed if compared to the current meta. As the patches from the second half of the season and the new champions are released, the meta will continue changing, regions will find what works best for them, and regional and international tournaments are going to play out in favour of those teams who find the best strategies. In MSI the Asian teams made a statement. Now it is up to the rest of the world to get up to speed.

Will this be the year when Europe finally wins the Worlds trophy again after nine years without luck? Will Solo Queue players continue being one-shot by over-tuned champions on release?

These are mysteries that cannot be answered yet. Riot’s balance team will have an important role to play for both questions. But it is clear that it is this uncertainty and a constantly evolving game that makes League of Legends and eSports as a whole as exciting as it is.

For us at Bayes Esports, the dynamism of the scene is both a blessing and a curse. A blessing, because the constant evolution of the game keeps research interesting and brings lots of opportunities to explore. A curse, because we need to be constantly aware of the effects of in-game changes on our products. But as they say, if it’s easy it’s not worth it, and as a Data Scientist at Bayes, there is little space to get bored.