In the press room at Oviedo, the smiling figure of Santi Cazorla emerges. He has not been part of his team’s come-from-behind win over Eibar due to an injury. “A small thing. Nothing serious.” But he is central to everything at Real Oviedo right now. He is home.

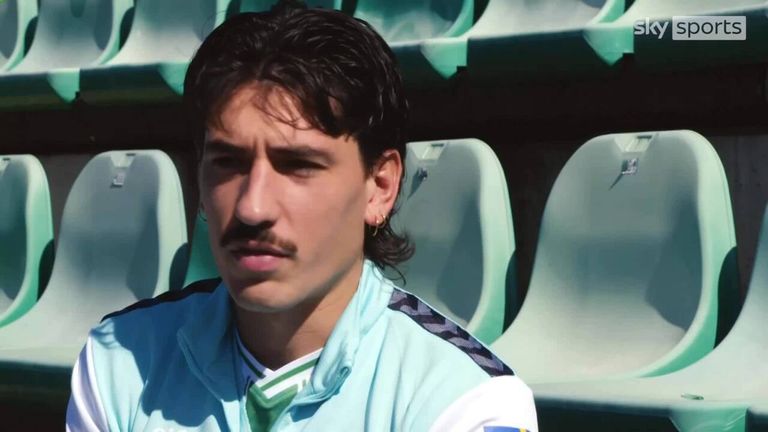

At 38, Cazorla is back at the boyhood club that he was forced to leave as a teenager and he wants everyone to understand just what that means to him. “This is really, really important for me,” Cazorla tells Sky Sports. “It has been everything that I expected.”

Earlier in the afternoon, speaking to club president Martin Pelaez, he revealed the unseen influence of Cazorla on the victory later that day. It was the veteran’s insistence on playing for the minimum permitted salary that freed the club up to make other signings.

“The truth is that he helped us a lot,” Pelaez tells Sky Sports.

“From the first moment, he told us that the economics would not be a problem and that is how it was. This was Santi’s will. He did it out of affection, out of love for his city and his people. The fact that he did it gave us the salary space to bring in Santiago Colombatto.”

Who scored the late winner on Sunday? Colombatto, of course.

That goal sparked celebrations inside the Estadio Municipal Carlos Tartiere in this picturesque city in northern Spain but the feel-good factor here runs deeper than any late winner. It is the sense of pride and identity reinforced by the return of Cazorla in the summer.

“Some repercussions can be measured,” says Pelaez. “The shirt sales, the coverage that Oviedo has received.” Membership has exceeded 20,000 for the first time. “But there are things that cannot be measured such as the impact that this has had on the city.”

Cazorla’s homecoming had been longed for in this part of Asturias. They have celebrated his career, watching from afar as he twice helped Spain become champions of Europe. At Arsenal, he lit up the Premier League with two beautiful feet and one brilliant brain.

But Oviedo was always the club of his heart. “This is a special place for me,” says Cazorla. “I played here many, many years ago when I was only young.” It is the club where he had once been a ballboy, the city that he had never fallen out of love with.

But a financial crisis, a double relegation, led to the scrapping of the B team and effectively left this teenage talent without anywhere to play. And yet, almost a decade on, it was those same financial difficulties that inadvertently deepened his connection to the club.

In 2012, with Oviedo on the brink, the club was saved by a global campaign that raised €2m inside two weeks. Oviedo now has shareholders in 125 different countries. Cazorla, along with fellow former players Juan Mata and Michu, was a significant contributor.

For Agustin Lleida, Oviedo’s general manager, this feels symbolic.

“It takes us back a little bit to football’s origins,” he tells Sky Sports.

“I think that is important because nowadays football has become very commercial, sometimes even artificial. That there are still players who love the shirt, who are fans of a team, even in such an artificial and commercialised industry, I think that is beautiful.”

As well as playing for the minimum wage possible, Cazorla has handed over his image rights and insisted that 10 per cent of his shirt sales are reinvested in the academy of which he was once part. Significant when 40 per cent of all shirt sales bear his name.

“The young players, the academy, that is really important for the club,” says Cazorla. “I just want to help all of them. They are the future.” And that future is brighter because of his presence. Lleida does not underestimate the impact of his influence.

“For the youngsters who are coming up from the academy, he is a very positive example. I am sure he is going to transmit a lot of values during this year that the kids moving up the first team can learn from. In the end, they will copy what the greats do.”

That impact on others extends to the management. Everyone knew Cazorla’s reputation as an affable and humble presence, but there is both surprise and relief that he has exceeded expectations. “He is a great human being,” says Pelaez. “Always laughing.”

Laura Gonzalez-Manjoya Peon, the suddenly overworked head of communications at Oviedo, has been amazed. “He is a joy to work with on a day-to-day basis. Even if he doesn’t play, I ask him to do an interview or speak to the sponsors and it is always a yes.”

Lleida adds: “Everyone was waiting to see how he would be. Even though he touched the sky as a player, his feet are on the ground.”

He jokes that he recently asked the players who the most famous contact that they had in their phone was. One answer came back.

Given this adoration felt by team-mates and colleagues, let alone the public, it is easy to see this as a zero-risk move by Cazorla.

Speak to those close to him and a slightly different picture emerges. Some were concerned. He has nothing to prove, that is true. But this is the city where his children go to school, where he hopes to grow old. A fear was that playing on risked diminishing his legacy.

Cazorla’s modesty means that one can detect this thought in him, that maybe all this is a little too much for someone who has never sought the spotlight. “I want to say thank you very much to all the people here,” he says. “Because they love me too much.”

Everyone has a favourite Cazorla moment so far. For Pelaez, the president, his are understandable. “The first moment was on that telephone call when he said yes. The second was the presentation in the stadium. That was big.” Oviedo sold 3,000 tickets for that.

For Gonzalez-Manjoya Peon, it has been the appearances away from Oviedo. “They applaud if he takes a corner,” she says. “The management applauds if he comes off the bench. The fans of that stadium applaud. It is something super special. It is recognition.”

Something similar was reserved for Andres Iniesta after his World Cup-winning goal in 2010 but, as a Barcelona player, even Iniesta was central to the country’s biggest sporting rivalry. Cazorla played for Villarreal in the east and Malaga in the south before returning north.

He is embraced by all.

Lleida agrees. “When he came off against Zaragoza, a field with a lot of history, La Romareda, a World Cup stadium in 1982, the whole stadium stood up. It is something that represents what he has achieved. And I think it is only fair for him to be recognised.”

The hope is that the best moments are ahead. That first goal in an Oviedo shirt? Cazorla has been waiting most of his life for that one. With the team now into the top half of the table, promotion remains a possibility. “I want to try to help the club go up,” he says.

But this story is not really about that.

“We have not brought Santi in because we were looking for him to make a big difference on the field,” concedes Lleida. “Santi doesn’t have the physical capacity of a decade ago. But on a technical and tactical level, he has not lost that and he has contributed already.”

Pelaez puts it more succinctly.

“I would have signed him if he were 45.”

The important thing is that he is back.

“Our idea and his idea is that he stays at Oviedo. I don’t know if he will be a coach or go in another direction but he will surely continue to be involved in football and there will be an open door here. This is his home. His impact here will be permanent.

“And for us, as professionals, we have the distinction, the fortune and the honour of being part of this important moment.

“The return of the prodigal son.”