Given that Civilization creator Sid Meier famously defined a game as a series of interesting decisions, it’s ironic that the most interesting decision one ever makes in Civ comes before you start playing: which civ will you pick?

Humankind’s biggest idea, though it has many, is to ask this question whenever you enter a new era, which you’ll do six times over the course of a game. This takes nothing away from the weight of each choice; as in Civ, every ‘culture’ has a unique unit, city district, and trait, all of which nudge you into a particular playstyle. It’s a big deal every time.

Indeed, Humankind’s genius is that this decision only gets more interesting as the game unfolds and your circumstances come to bear. The Egyptians are one of my favourite picks in the Ancient era because their pyramids give a huge boost to industry, but prioritising their construction can leave me low on food. Since I need that in order to make people – an important component of any civilisation – I like to opt for the agrarian Celts in the Classical era.

But that’s considering the question in the abstract. Circumstances are everything. Have my scouts discovered a neighbour with violent tendencies? Better pick a militarist culture to defend myself. Or have they found a large tract of uncontested land? An aesthete culture can produce the influence I need to claim it. Strategy games are all about solving problems, and to accurately assess my current challenges, pick a culture to conquer them, and then see the plan play out is deliciously satisfying. I flood my empire with the Celts’ food-producing Nemeton districts, my population starts booming, and I all but cackle with glee.

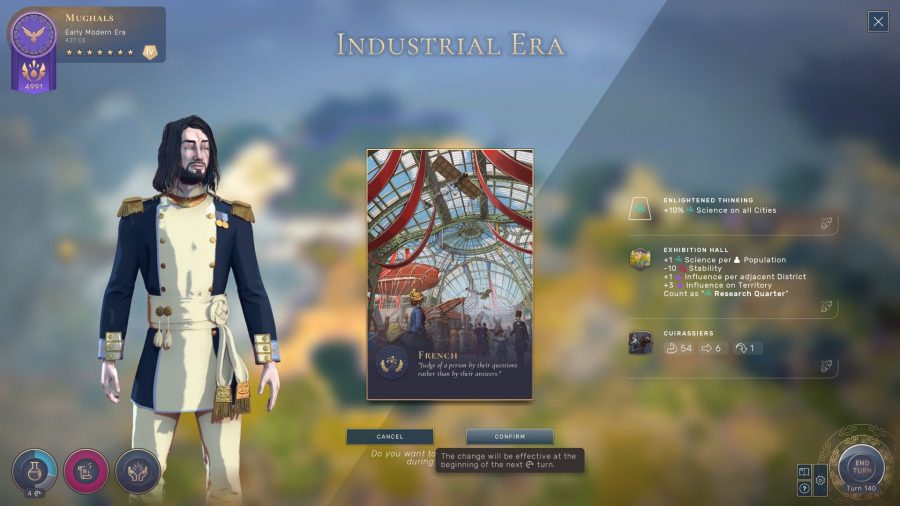

Each game is a series of these eureka moments. I spam France’s Exhibition Halls in the Industrial era, and even though the following Contemporary era has the most expensive techs, I’m delighted to find I can research most of them in just a couple of turns with no further science investment. With each game I finish, I can’t wait to start another and make more discoveries.

You do you

In another of Humankind’s bright new ideas, you can create your own avatar and even decide how it will behave when the AI plays as it, creating its personality by assigning traits and buffs that you’ll unlock via in-game achievements. You can then share this avatar with your friends to use in their games.

This process is the core of Humankind, and because the circumstances are so variable, so is the process. Though some cultures’ bonuses are more niche than others, and some (like the Celts or the French) are pretty overpowered in theory, your in-game needs will ensure the decision is always as interesting as Sid would wish. Experimenting with new cultures creates tremendous replayability, and because you’re doing so under the pressure of events, there are stakes which just don’t exist in Civilization.

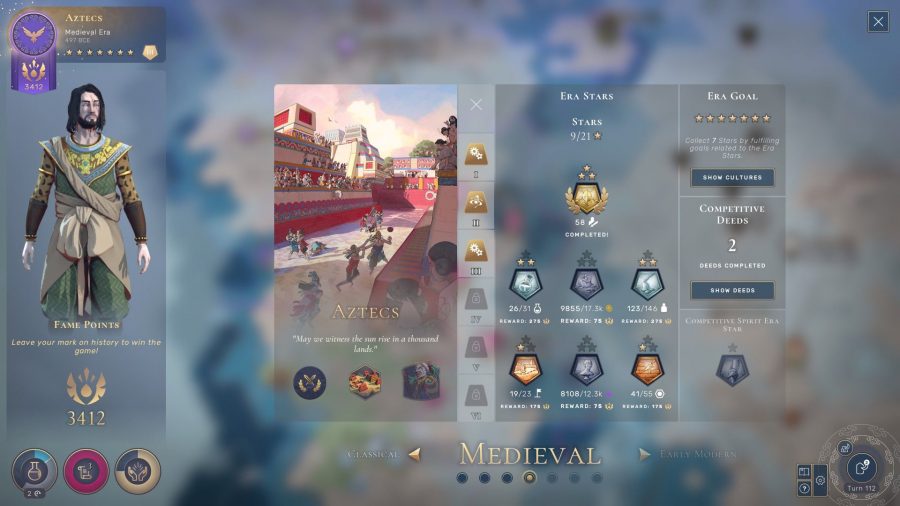

Your goal is to accrue ‘fame’, an objective as flexible as your adaptive civilisation. In Civ, most civs’ traits commit you to one or two of its particular victory conditions, but in Humankind you’re awarded ‘stars’ of fame for your progress in seven paths of endeavour – building things, making money, killing enemies, and so on. While each culture has an affinity for one of these paths, they’re all open to you at all times.

This does have its drawbacks. Civilization’s intricate victory conditions are part of how it achieves its own variety; supplying a world-conquering military looks very different from winning votes in the World Congress or filling your empire with art, to say nothing of its take on how religions compete. Flitting between seven much shallower forms of activity doesn’t require the same level of planning. But this is probably a matter of taste: play Civ if you want to follow a long-term strategy, play Humankind if you fancy reorienting that strategy at regular beats.

Each game is a series of eureka moments; I can’t wait to start another and make more discoveries

This can lead games of Humankind to follow similar rhythms. During its ‘OpenDev’ betas and press demos, I would have a massive scrap with the nearest AI whenever we ran out of unclaimed territory and started eyeing up one another’s, which usually happened in the Classical or Medieval eras. After winning these showdowns, I would snowball to total dominance, depriving the rest of the game of much challenge.

This phenomenon has improved. There’s still some tension when land runs out, which is appropriate, but if your neighbours are friendly it doesn’t have to lead to war. Independent tribes are also much more active now, and will claim territories left vacant for too long, throwing a spanner in everyone’s plans. They can be conquered, or charmed, traded with, and eventually assimilated more peacefully into one’s empire. If you have the ‘New World’ option enabled in setup, you’ll find a whole continent untouched by major powers, but with a number of these independent peoples for you to meet – a recreation of the circumstances encountered by European powers in real life. How you interact with them is, of course, entirely up to you.

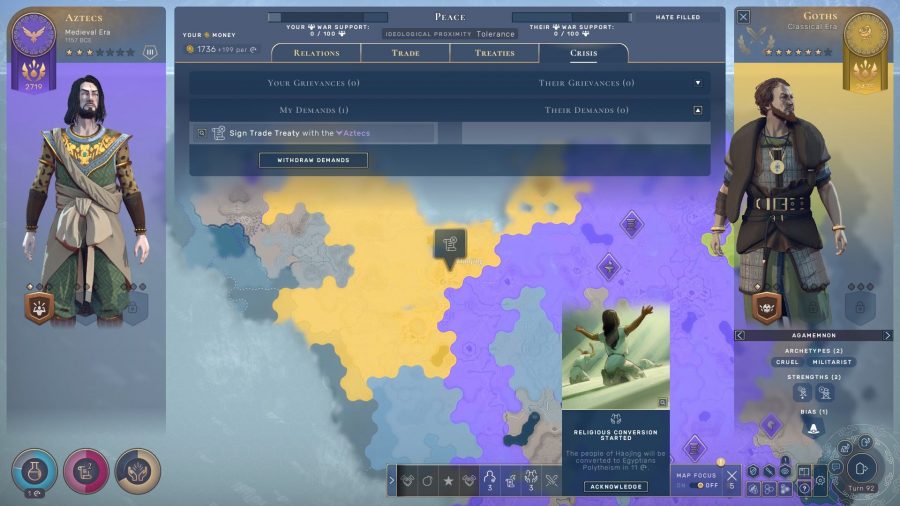

Relations with the AI feel similarly dynamic. Diplomacy is fueled by behaviour in the world; you can demand compensation for transgressions or let them slide, and in the latest version of the game you can make a fuss over almost anything – even if the AI so much as declines a treaty proposition. But because you can also forgive these slights, you have many more options for generating and dissolving tension, which keeps AI relations at an exciting simmer.

I’d still like more methods of interaction in diplomacy, such as exchanging territory or money, so that I can solve more disputes without force. But I’d really like the AI to recognise some of the nuances of third-party interactions. In my second game I was allied with most of the world until the Persians suddenly betrayed me, so I called on my allies to back me up. Not many of them did – which is fine, honestly – but they came to regard me as the warmonger simply for making a demand out of their inaction and for defending myself, which felt unfair.

You can throw further curveballs into your game at the setup stage. It’s possible to tweak tendencies of topography and climate, and frequency of islands, rivers, continents, and more to a good level of detail, and the effect these variables have on your encounters with the AI can be dramatic. A warmonger looks much less scary from the other side of an ocean, obviously, but even mountains and hills matter a great deal in Humankind because of its brilliant combat system.

When it comes to battle, your armies will unstack and spread across the map. You’ll need to consider the terrain – high ground, rivers, choke points, city defences and so on – when deploying and moving your troops, and larger battles can take multiple game turns to resolve, so you can also bring reinforcements into the fight in the meantime. Think of the Prussians bailing out Wellington at Waterloo, or the Spartans funnelling Xerxes’ armies into the Hot Gates at Thermopylae. Now think of the role that legendary upsets like these have played in the history of warfare, and it feels a bit shameful that Civilization doesn’t have a system to replicate them. In Humankind, you can prevail against two-to-one odds through clever use of terrain and reinforcements, and it feels both brilliant and historically accurate to pull off.

It doesn’t always work. Certain unit abilities, or tricks like specifying a particular tile from which to attack an enemy, aren’t obvious and are poorly signposted. I can’t besiege cities that cover whole islands with either ships or land units embarked on ships, which means I can’t take them at all, ever, which is a big problem on maritime maps. And that’s Humankind in microcosm, really: ingenious, game-changing new ideas that are occasionally marred by bugs, wrinkles in implementation, or feel just a tad underdeveloped.

Religion is a good example of the latter. Without making any effort to do so, I always get the chance to develop a religion, and provided I build the odd religious monument when the mood strikes me I can usually spread it widely and level it up. I don’t want Civ VI’s bizarre carpets of priests shooting lightning at one another – I really don’t – but Humankind’s alternative is currently rather threadbare.

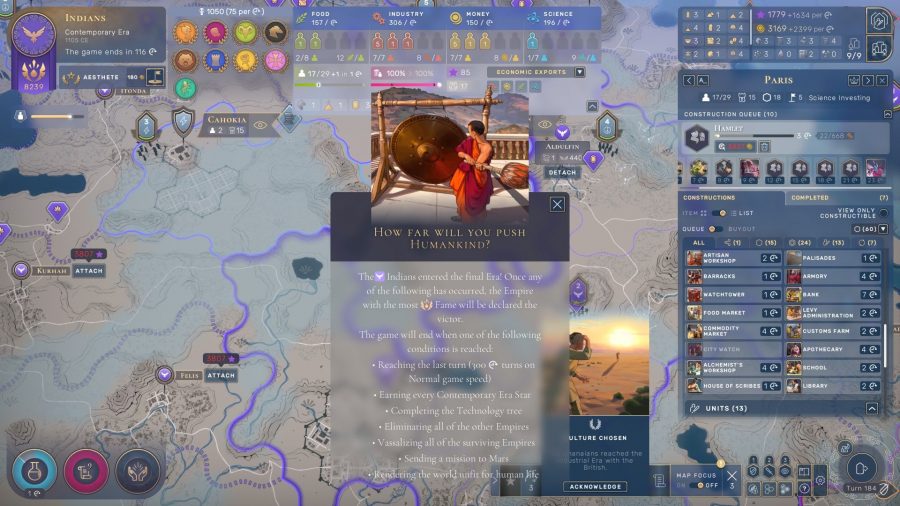

As for imbalances, several events can ‘end’ a standard game, at which point your fame score is taken and a winner declared. One of these events is completing the tech tree, and it’s the only one that I’ve seen in three games – none of the others come close to happening first, even when I’m not chasing science. I’m yet to see the mildest impact of pollution, or to build a nuke, since the game is so stingy in seeding the strategic resources required. These seem like variables that would be good to be able to adjust in setup. Fortunately you can adjust the ending triggers, and you can choose to keep playing even after a winner has been declared.

A few notable bugs and other oddities: I’ve seen unit models disappear from the map, an AI unable to resolve its siege of an independent city for an entire game, and my income plummet from +20k per turn to -127k per turn overnight. One AI seems able to build reputation with every independent city on the planet from the start of the game despite never having met them, meaning they can assimilate them and take a chunk of territory in my back yard whenever they want. And for some reason, there’s a limit on the number of save files I’m allowed.

A few ripples of frustration, then, most of which can and probably will be fixed at some point. There’s only one area where, for me, Humankind falls short of the competition in a way that probably won’t change: charm. It’s beautiful and charismatic – its artwork is gorgeous, with a lovely pastel palette, and it boasts a honey-voiced narrator who will make gently whimsical observations about your journey at regular intervals. Nonetheless, something about it leaves me a little cold.

Maybe I’m used to Civ VI’s initially divisive art style at this point, but I miss the personality of its AI leaders, the warmth of its colours, and the pop of its in-game models. Humankind’s cities look less distinctive, and I predict with confidence that none of my rivals will inspire memes like Alexander the Great’s portrayal as an annoying warmonger jock, or “would you be interested in a trade agreement with Eng-land?”, or, of course, nuke-happy Gandhi. These fluffy things are a bit subjective, but they do matter when it comes to emergent storytelling. I was annoyed when the pink lady betrayed me and none of the other Power Rangers came to help. But I hated Alexander from the moment I saw his smug little grin.

That aside, however, Humankind is mostly brilliant. I’ve been making a lot of Civilization comparisons in this review, but that’s inevitable considering the similarities, and the fact that Humankind fares so well against the grand daddy of this genre is a major accomplishment. It’s an easy recommendation if you like 4X games, and well worth checking out even if you don’t. But it doesn’t feel like it’s reached its final form just yet.

{“schema”:{“page”:{“content”:{“headline”:”Humankind review – does Civilization’s challenger measure up?”,”type”:”review”,”hardware”:”Razer, Razer Tartarus V2 Mecha-Membrane Gaming Keypad”,”category”:”humankind”},”user”:{“loginstatus”:false},”game”:{“publisher”:”Sega”,”genre”:”Strategy Gamer”,”title”:”Humankind”,”genres”:[“Strategy Gamer”]}}}}