The following blog post, unless otherwise noted, was written by a member of Gamasutras community.

The thoughts and opinions expressed are those of the writer and not Gamasutra or its parent company.

This was originally posted to my personal blog, if you want to read it in its original location.

I feel like hard counters get a bad rap in RTS games. There are a lot of arguments out there both for and against such systems, but I’ve been thinking about them a lot lately and I honestly wanted to try to lay out a clear case for why I think they’re an affirmative good in real time strategy games, at least from my perspective. As per usual, I think nuance is going to get in the way of things a little bit, but let’s give it a try.

As always, I’m going to start by defining my terms. In an RTS, a ‘hard counter’ is an interaction where it is practically or actually impossible for one unit or army composition to defeat another unit or army composition. I want to mostly talk about unit hard counters rather than army or strategy hard counters, but the two are related.

So, just as an example: in an hypothetical real-time strategy game, we might have 2 units: one is a ground-based infantry unit which can only attack ground targets. The other is a flying unit which can attack ground units but not other air units. In this situation, whether or not the flying unit is designed to effectively kill infantry units, the air unit is a hard counter to the ground unit in this example. The ground unit cannot hurt the air unit in any way, and the air unit can hurt the ground unit. This relationship is based on innate and immutable differences between the two unit types.

There is no situation in C&C 3 where Riflemen beat Flame Tanks, thanks to damage bonuses and penalties on both sides

As a second example: let’s take a look at the Flame Tank and Rifleman Squad from Command and Conquer 3. The Flame Tank deals bonus damage to the Rifleman squad, which in turn deals drastically reduced damage to the Flame Tank. Practically, the Flame Tank will melt almost any number of Riflemen while the Riflemen will never kill the flame tank in a reasonable amount of time. This is another hard counter. In this case, of course, the relationship relies on damage bonuses and penalties instead of innate unit attributes, as the previous example. We’ll look into damage bonus and penalty systems later on in this piece.

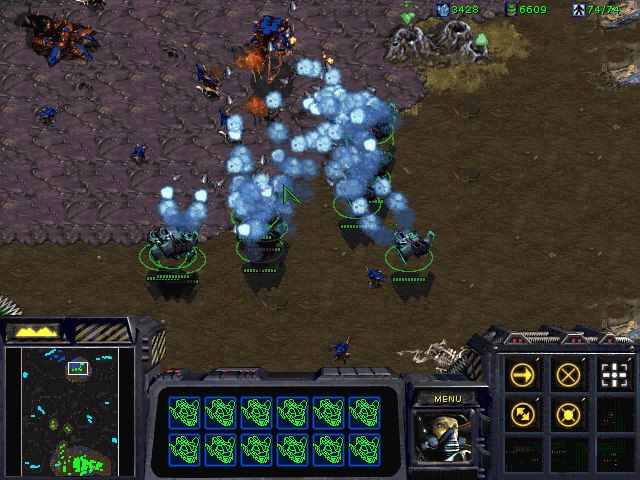

To be super clear: a hard counter is a practical evaluation of the relative capabilities of the two things being compared. Damage bonuses and penalties alone don’t make a ‘hard counter’ system. For instance, the relationship between the Baneling and Marine from StarCraft 2 is sometimes considered a ‘hard counter’ – Banelings will always kill Marines instantly when they hit them. But practically, Marines and Banelings are a ‘soft counter’ to each other, since Marines can and do come out on top in this relationship based on the player’s control over their units. A more true ‘hard counter’ relationship between the Baneling and Marine might be if the Marine couldn’t damage the Baneling effectively, or if the Baneling’s explosion radius were much larger and it had more health.

Another way to look at hard counters is the amount of resources required to overcome the health reserves and damage output of the opponent’s unit(s). In the Marine/Baneling relationship, it’s pretty easy for either unit to come out on top in terms of making the player’s opponent trade badly in terms of cost efficiency. In the relationship between the Flame Tank and Riflemen, the Flame Tank can take out its own cost in Riflemen many times over, requiring the opponent to choose another tool to deal with the Flame Tank.

The harder the counter, the more cost efficient the trade will always be between 2 participants in combat. As with the air unit example above: that 1 air unit cannot be killed by any number of those ground units. Now, of course, the ideal situation would be if the air unit in question was designed to kill infantry. A combat scenario where you have an air unit that can’t adequately damage its target on one side, and a ground unit that cannot hit the air unit at all on the other side is just flat out boring. Technically by my definition it counts as a hard counter, but that particular gameplay outcome would be a problem since on both sides you have an uninteresting and unsatisfying engagement.

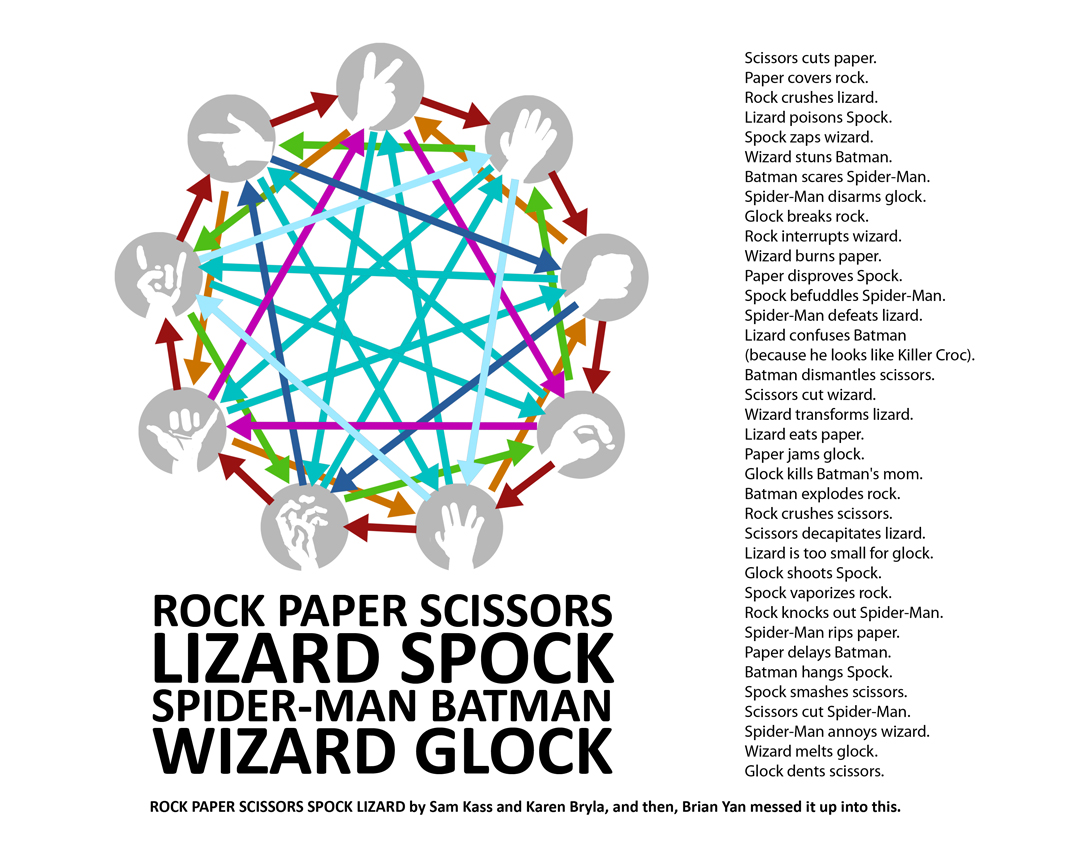

So, in the classic kids’ game “Rock, Paper, Scissors” you have these 3 binary relationships you’re dealing with. I won’t go into it because I assume that’s common knowledge and if it isn’t, Google it I suppose? Often, hard counter systems are called “Rock, Paper, Scissors” or RPS systems. I have a bit of a quibble with this.

In practical terms, in RTS games you’re almost never going to have a “rock” unit that will instantly and immediately invalidate the entire presence of “scissors” units from the game in a binary way. There may be relationships where the “rock” unit invalidates the presence of all nearby “scissors” units but even in small scale RTS like Company of Heroes, having powerful anti-infantry options on the field doesn’t mean that infantry are all of a sudden useless. They might be better suited elsewhere on the map, or used to lure the anti-infantry vehicle into a trap, but they still have a role in the game.

To me this is one of my key frustrations with regards to talking about hard counters vs soft counters. There seems to be this assumption baked in that hard counters existing means that things are going to rapidly become pointless to make and impossible to use just because their counter is on the field.

Which, in some worst case scenarios, might technically happen? To to pick up our Command and Conquer 3 example of the Flame Tank and Riflemen again: if I have an army of nothing but Riflemen squads for some reason, and my opponent creates a couple of Flame Tanks, and for some reason there’s nothing else I can produce then I’m probably screwed. But, realistically, this scenario isn’t going to happen. In fact even in the above example I’d want to keep my Riflemen alive as much as possible for potential use in other situations.

In a practical sense, one way to think about hard counters that I find very helpful is to think of them not in terms of “this unit is very good at killing that target type” but more in terms of “this unit is very bad at killing that target type.” To me, the unique element of hard counter systems not that some units get instantly deleted from the game if you have a certain unit type on the field; it’s that ground unit that cannot attack that air unit, or that Rifleman that will just never do enough damage to take down a tank.

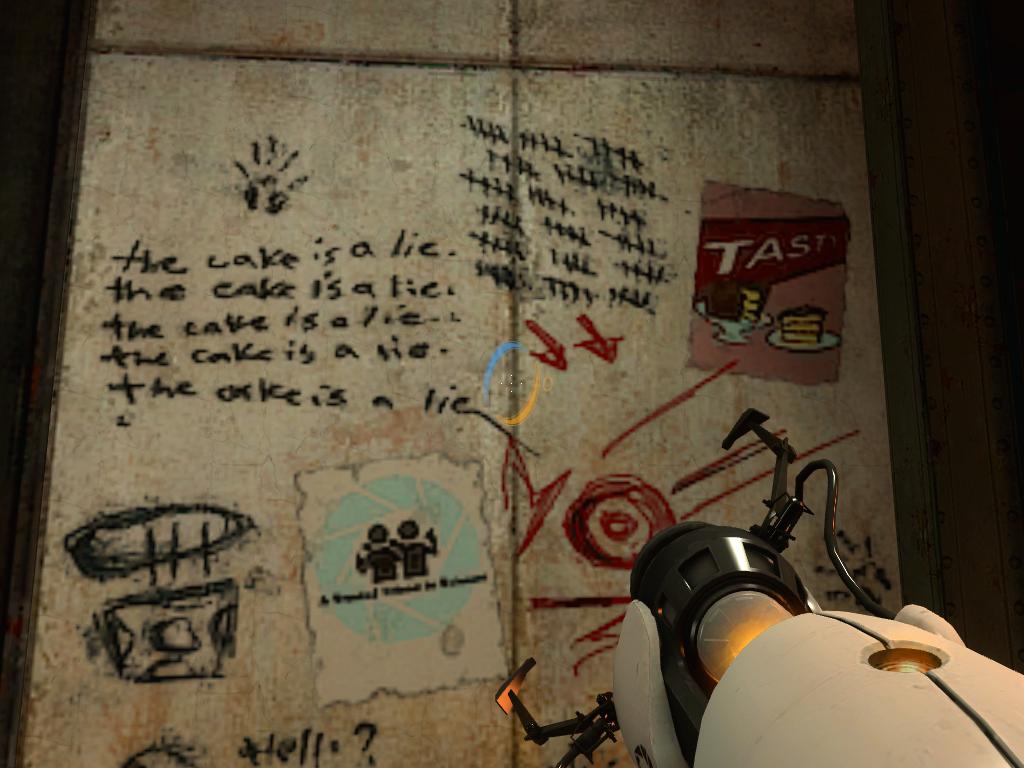

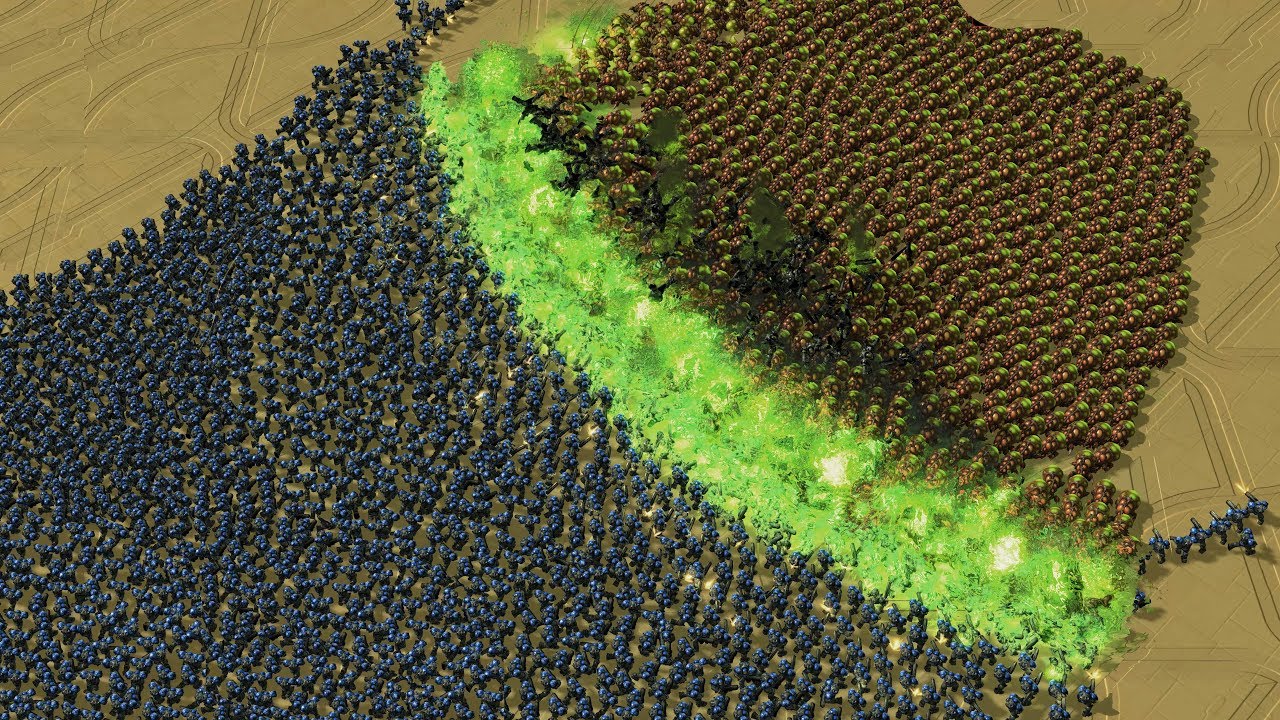

OK: I’m having a bit of fun with the above image. Soft counters aren’t a “lie” of course. But in my years as a student of RTS design, I have found that it’s fairly common for things to not have the effect on a game that players or designers might have desired or anticipated when they set out to create (or play) a particular game.

In my experience, what happens in games with a lot of focus on ‘soft counters’ tends to break down a bit, especially with large numbers of units in play, towards a place where whichever side has the most overall health and damage in the combat will just win.

Since we defined ‘hard counter’s let’s take a second to talk about soft counters and how I’m defining these. If the ‘hardness’ of a counter (as defined above) is the pure cost efficiency of a tradeoff: “I put $2,000 of something on the field it can wipe out $20,000 of something else.” Then a soft counter would be much lower than this, less than something like a 2:1 cost efficiency ratio for an encounter.

Now remember, we’re talking about gameplay outcomes here. So in terms of gameplay outcomes, the baseline assumption is that if cost efficiency is more equal between units, then other things like positioning and micro can come more into play, and the player who controls their units better will win. Right?

Well, maybe? That might represent a best case scenario for soft counter systems. I think though in conversations about counter systems, one bad baseline assumption that’s made is looking at best-case scenarios for soft counter relationships and worst-case scenarios for hard counter relationships.

I view the overall goal of RTS combat to be focused around players utilizing positioning, micro, and unit abilities to come out on top in an out-and-out battle, as well as harassing the opponent’s structures and economy where possible. But, as I said above, it feels like with ‘softer counter’ systems, the big baseline are the total health and DPS of the units in a battle.

In games with a higher prevalence of harder counters, at the very least the potential pool of effective HP is divided between the various counter types. For example: if the counters are infantry, vehicles, and air units, your effective pools of health reside with those 3 separate categories of damage types (with the possible caveat of damage types which might be effective against more than 1 of the above). In softer counters, sheer effective DPS and HP in one area can be enough to win a fight.

Due to this, it’s common for players in games with softer counters to rely heavily on high powered generalist DPS and AOE units where possible, due to the high efficiency in cost and target opportunities. Actually the same thing tends to happen in games that have harder counter systems, as well: reliable generalist DPS (like the Terran Marine in StarCraft 2 or the Tengu in Red Alert 3) is often a constant thorn in the side of players and gameplay designers alike.

In several Command and Conquer games, I believe this was referred to as the ‘medium tank problem’ – faction’s mainline battle tanks were cost efficient and well rounded to the point that many games came down to whomever was best at building and preserving their tank ball. Now, of course, this isn’t all down to ‘counters’ of course: units can overperform roles just fine without blaming it on something like a game’s ingrained counter system. But units which are too useful and too well rounded in general are a definite problem in many RTS games, and cut down on the depth and fun of these games. And in my mind, this is harder to achieve in games with effective hard counter systems.

To me, both hard counter and soft counter systems can result in the sorts of highly dynamic combat scenarios I was talking about above, but each has its own tradeoffs. You need look no further than a game like Red Alert 3 for an example of a really deep and fun game with a hard(er) counter system, and to StarCraft 2 for a depth and fun with a softer counter system.

For games with a larger number of hard counters, there are a couple of potential issues that typically come up: two unit types which aren’t designed to counter each other fighting each other is one of the worst ones. As with the “air unit that doesn’t do good damage against infantry units, fighting an infantry unit that can’t attack air” above: this is the “rock vs rock” in Rock, Paper, Scissors: not much happens. Actually, of course, a true “Rock vs Rock” situation would be where you have 2 units and neither can attack, block, or impede the other unit in any way. To me, as much as this is an issue in the first place (I don’t really see it as an inherent problem with RTS design) it can affect any sort of RTS.

In fact I’d go so far as to say that an RTS without “rock vs rock” interactions is one that you wouldn’t really want to play in the first place. Do you really want something like the Firebat to be able to attack the Valkyrie, after all? Or Valkyries to be able to attack workers? We already know there are combat relationships we don’t want to see, and there are ‘rock paper scissors’ interactions built into most RTS.

But, I’m digressing a little bit. I’m supposed to be talking about the weaknesses in both soft and hard counter systems.

I already talked a bit above about how, with softer counters, pure HP and DPS values tend to become more dominant, since (at the least) harder counter systems tend to divide the effective HP and DPS pools of a player’s forces into more ‘buckets’ or categories.

On the flip side, with harder counter systems, the biggest thing you get in terms of downsides are a larger percentage of unit matchups that can feel one sided or bad to a player. This is contrasted with the “Firebat vs Valkyrie” situation I mentioned above, which is another interaction that wouldn’t feel good. But being on the losing end of the “Flame Tank vs Riflemen” scenario I keep coming back to also feels pretty bad.

Generally, earlier in the game is when harder counter systems tend to feel worse. Later in the game, larger armies give the system more room to resolve into fun encounters with sufficient depth, control, and interest. This could be a case for hard counter games to include softer counters in the early game phase and ramp up the severity of the counter system with later game units?

With harder counter systems, it’s smaller combat situations that tend to feel the worst. In the early game, when you have very few units available, is when hard counter systems tend to feel the worst.

Another danger of harder counter systems is that units have a propensity to be reduced to a damage type and unit type. This can lead to really boring unit design where “shoots X gun” and “is Y unit type” becomes a lot of the core design of the unit. Games like C&C Generals and especially Red Alert 3 prove this isn’t necessary, however.

To me, the ideal design of a unit is that it performs some unique function for the player, which the player can exploit or use skillfully in order to help overcome their opponent’s units and abilities (there’s a whole can of worms there I can’t wait to address at some point in the future)

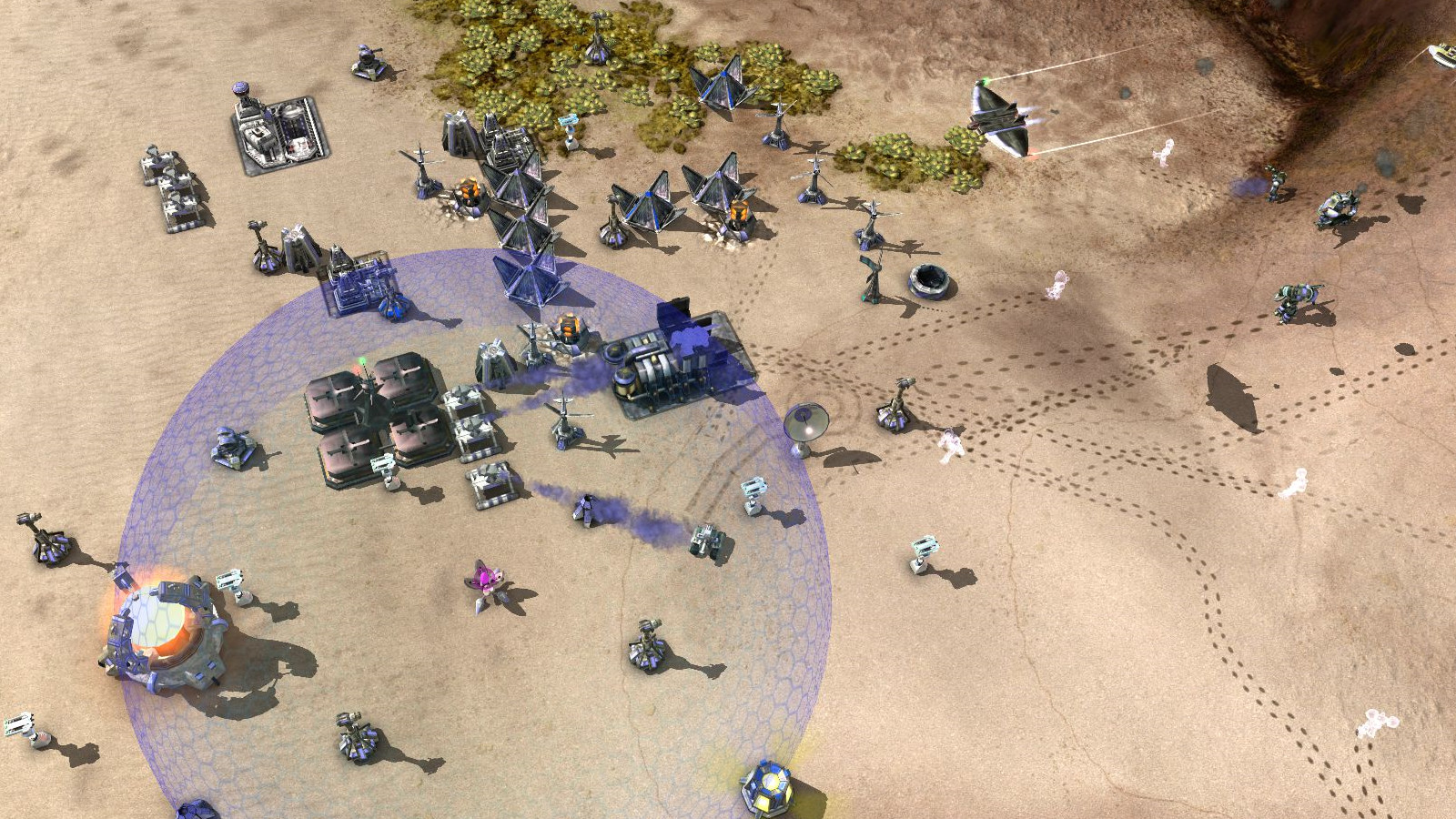

Free RTS Zero-K utilizes an attribute-based counter system, where Red Alert 3 is a good example of a hard bonus-and-penalty counter system.

When most people think about ‘hard counter’ systems, they seem to think about what are commonly called “RPS” or “Rock, Paper, Scissors” damage systems. I talked about that a bit above, but I feel like this is a bit of a misnaming. Basically, these systems assign “unit types” and “weapon types” to units, and provide various bonuses and penalties to unit damage based on the target and weapon type.

These bonuses and penalties are found in both softer and harder counter games. For instance: Warcraft 3 uses such a system, as does StarCraft 2, and as do Battle Realms and Command and Conquer: Red Alert 3. However, in Battle Realms and RA3, the damage bonuses and penalties tend to be a lot more emphasized, with 75% or more damage reductions on some matchups and 300% damage bonuses on other matchups.

We’ve already talked about Attribute design as well, using more immutable design attributes such as: this unit cannot target air units. Or, this melee unit cannot catch up to that fast ranged unit in order to attack it. Or, this unit has a high damage, slow attack, which makes it good for taking out high HP targets but bad at taking out numerous low-HP targets due to its low rate-of-fire and overkill per shot. That sort of thing.

These two systems are of course not mutually exclusive and are actually used together fairly often. And, as I said, such systems are often seen together in many games. Zero-K is one of the premier games that uses attribute-based counters, an Red Alert 3 is one of the better examples of bonus-and-penalty based counter systems.

Combat in Battle Realms is particularly unintuitive thanks to its dense counter system

The tough thing about bonus-and-penalty counters is that they’re often unintuitive. While it does make sense that a regular troop with an automatic rifle is not going to be able to take out a tank, it is somewhat less believable that a tank shell would glance off of a regular solider without blasting him to smithereens. In Command and Conquer 3, I believe, tank shots actually have a visual of missing their target, which helps ‘sell’ the counter relationship a lot better.

Warcraft 3 and to a greater extent Battle Realms have particularly dense counter relationships. I’ve played both games for years and it’s still frustrating to me that it’s impossible in many cases to tell the counter relationship between unit types without just memorizing them. Which units do piercing damage vs which units do bludgeoning damage is often possible to determine (Battle Realms’ Lotus clan units sometimes make this difficult though: does acid spit do piercing or does it do some other kind of damage?) but armor types can sometimes be really unclear. Why one unit takes triple damage from a sword versus the unit next to it taking 25% damage from the same sword is a matter of memorizing tables and playing over and over – there’s no good visual indicator for the player to use. This, along with the terrible feeling when you run up against something that just flat out deletes your army, are some of the worse feelings brought on by harder counter systems.

There are, of course, other damage systems: in Grey Goo, each unit has an Armor rating and an Armor Piercing rating, and the relationship is pretty much what you’d expect: Armor Piercing ignores that much of an enemy’s Armor value per attack. Possibly more understandable than unit types and weapon types? But it can still be a bit confusing since it’s sometimes not obvious what might have Armor and what might be good at hitting a target with an Armor value.

Anyway, in a counter system, the big differentiator isn’t in the specific system used, but in the impact that system has on the gameplay. Generally, bigger bonuses and penalties lead to harder counter scenarios, of course.

This is where things get a little tricky: “hard counter” games actually themselves often contain a ton of soft counter relationships. In RA3, for instance, when Allied Peacekeepers meet with Soviet Conscripts, or when Soviet Flak Troopers have a run-in with an enemy Sickle. There’s a situation where both units have kind of an equal chance of coming out on top. This is great actually, in my book: soft counters are fine to me (despite my joke above about them being a ‘lie’) and definitely have a place in any RTS. Just, keeping in mind that the game being reduced to whoever has the bigger pool of HP and DPS, is a really bad outcome.

The really important thing in a game with hard counters is, uh, the actual availability and prevalence of hard counter relationships. That tank that’s good against infantry is a ‘soft counter’ to anti-tank infantry units, but the fact that it’s there to scare off or take out anti-air or anti-infantry is an important relationship. Weirdly, Command and Conquer: Rivals is almost a perfect stripped-down example of what I’m talking about here.

In C&C Rivals, the player always wants to pair off a unit with what that unit kills best (while keeping it away from things that are good at killing it). This leads to a surprisingly tense dance of counters being moved next to the thing they want to attack while keeping away from things that want to attack them. For such a simple and small scale game it’s got surprisingly deep combat with attributes as simple as “if X dies near my unit, Y happens” or “This unit performs that action when it’s stationary” or “this unit has a passive element that applies around itself while it’s attacking.”

In my experience, weirdly, games with a lot of hard counters tend to (when the game is reasonably well balanced, anyway) average out into combat scenarios where the hard counter relationships smooth out the gameplay. If you have tanks, units that are good against tanks, air and units that are good against air, and infantry and units that are good against infantry, you don’t have a series of “Rock, Paper, Scissors” binary deletion interactions, but a dance of players trying to find good angles of attack and trying to preserve their units in order to deter or destroy or drive off pieces of the enemy army.

As usual, I’ve written over 3000 words without feeling like I’ve more than scratched the surface of this topic. While I addressed (briefly) the idea of attribute-based counters, there’s a whole unexplored terrain there that I didn’t really feel like I had time to go into: non-damage based counters, like units which can prevent other units from attacking, or the simple act of deterring a unit or army with another unit or army. Time-based advantages are one of my favorite systems in RTS, after all.

Thanks for reading. Looking forward to comments, as usual, and I hope you’ll return in the future to read more of my ramblings about competitive RTS design.