What does the future hold for transfers? Which leagues will produce the next global superstars and what will the world-record fee look like in 2050?

As part of the Future of Football series, Sky Sports investigates the past and present, and make predictions for the future, based on data and projections from leading experts…

Transfer spending then and now: How high will fees rise?

Premier League clubs splashed a record-breaking £2.9bn on transfers last season, which marks an exponential leap from the previous record of £1.9bn set in 2017/18.

All of the top 20 most expensive signings during the Premier League era date since 2016/17, which was when Paul Pogba broke the world-record transfer fee after joining Manchester United from Juventus for £93.25m.

Before 2016/17, only three deals appear in the top 40: Angel Di Maria (£61m to Manchester United in 2014/15), Kevin De Bruyne (£55m to Manchester City in 2015/16) and Fernando Torres (£50m to Chelsea in 2010/11).

World-record fees have come a long way since Aston Villa paved the way when they splashed £100 on Willie Groves in 1893.

The six-digit figure wasn’t smashed until the 1960s, when Luis Suarez – not the former Liverpool striker – joined Inter Milan for £152,000.

Italian clubs repeatedly broke the world record from the early 1950s until the early 1990s, before La Liga muscled into pole position and dominated into the 2000s with Real Madrid’s Galacticos era.

Premier League clubs spent merely £40m on new signings in 1992/93. Across world football, that was the year Jean-Pierre Papin broke the world-record fee at £10m, days before Gianluca Vialli (£12m) and, then, Gianluigi Lentini (£13m) secured record transfers.

Compare that with 2022/23, when Premier League clubs splashed £2.9bn – 72 times the expenditure spent 31 years ago. Meanwhile, Neymar’s £198m move to Paris Saint-Germain from Barcelona in 2017 remains the world-record fee for a sixth year running and represents a 20-fold increase on Papin’s fee from 1992.

So, has inflation affected the exponential rise in fees? Not really. The British pound inflated 97 per cent between 1992 and 2017. Meanwhile, the record transfer fee soared 1,880 per cent during that period – 18 times above the GBP inflation rate.

Fees surge in women’s football

As attendances in the women’s game are soaring exponentially, a similar trend emerges with transfer expenditure: only £500,000 was spent on players worldwide in 2018, but that figure rose to £2.6m in 2022.

Manchester City smashed their club-record fee only last month, signing Jill Roord from Wolfsburg for £300,000 on a three-year deal – a new British record.

Only 22 players in the women’s game moved clubs for a transfer fee worldwide in 2018 – but that figure leapt to 98 last year, while the overall number of transfers has followed an almost identical trajectory, rising from 694 in 2018 to 1,555 in 2022.

However, disparities exist. UEFA clubs made up £2.2m of the £2.6m spent worldwide last year.

Rising revenues to bring rising transfer fees?

Speaking at the Opta Forum 2023, Stats Perform chief product officer Nancy Hensley summarised it best: “Women’s sports viewing in the UK has increased 131 per cent in the last year.

“Fifty million viewers worldwide tuned in to watch the Lionesses beat Germany, which was three times more than the previous women’s Euros; 14.3m Americans tuned in to watch the women’s football team win the World Cup in 2019 – compared with 11.4m for the men’s in 2018. So, the women’s football team viewership beat the men’s in the US.

“Attendance for the WSL is up by 300 per cent; 91,553 people packed the stadium to watch Barcelona versus Wolfsburg. The Women’s World Cup in 2019 ended up doubling the estimated advertising revenue.

“So this is a sport that is always underestimated but has tremendous momentum… The reality is that women’s sports here in the UK still only accounts for a seventh of [overall sport] coverage, so we still have work to do.”

The huge scope for growth, coupled with demand, suggests women’s football will expand its fanbase rapidly, receive more coverage, attract bigger audiences and generate more revenue. That growth is likely to drive transfer fees worldwide, albeit at differing rates.

Move over strikers! Which positions will cost the most?

A glance at the list of world-record fees in the What about record fees? section above underlines how strikers have typically been prized assets throughout history.

However, things have been changing domestically. Pep Guardiola jettisoned Joe Hart for a ball-playing goalkeeper when he joined Manchester CIty in 2016 and signed technical midfielders Bernardo Silva and Ilkay Gundogan, before spending over £100m on new full-backs the following summer.

Meanwhile, the two most expensive players in the history of the division are defensive midfielders: Enzo Fernandez (£106.8m) and Declan Rice (£105m) – with both deals completed in the past year.

Rampaging full-backs, who could endure running the length of the pitch and fulfil both defensive and attacking duties for 90 minutes became en-vogue – triggering a need for competent defensive midfielders who could drop, cover and counter-press to prevent dangerous counters in transition.

Forwards, in the form of inverted wingers, were prime estate for some time – arguably peaking when Mohamed Salah and Heung-Min Son shared the Golden Boot as recently as 2021/22 – often excelling most when playing alongside central strikers who drop deeper.

Currently, inverted full-backs, defensive midfielders who can destroy, pass and drive, ball-playing defenders and goalkeepers are in demand, as are left-footed players – to eke out every ounce of resource on the pitch.

However, Manchester City switched from deploying a false 9 to favouring a traditional No 9 in Erling Haaland last season – tasked with bullying and exploiting this new breed of defender and other top teams are hunting for equivalents.

We could be going full cycle.

Data-mining stars

The video game Football Manager has helped nurture generations of football-data fans. Over the years, clubs have accessed increasingly advanced databases to achieve exactly the same thing: scouring the globe for statistical gems.

Brighton are just one club harnessing data to build success: World Cup winner Alexis Mac Allister, who left the club to join Liverpool in a £55m deal in June, told Sky Sports last winter: “Brighton spoke with me and my agent and said I was one of the best U21 players with the best numbers – because Brighton work a lot with numbers and statistics.” The Seagulls registered £48m profit upon his departure – having signed the midfielder for £7m from Argentinos Juniors in 2019.

But that is just one example: data analysis is becoming an essential process across the sport – for squad performance, fitness, tactics and recruitment. Deloitte predicts data is now set to play an increasingly important role in maximising revenue streams.

Stats Perform, widely referred to as Opta, is just one company offering data-driven recruitment software, merging event and tracking data with video – allowing clubs to search player profiles from around the world.

Senior vice-president of innovation at Stats Perform Brad Griffiths told Sky Sports: “I think there are two foundational things when it comes to recruitment with data: you need scale and consistency. The scale enables you to look in a very broad market and the consistency is absolutely key. The game looks very different in different competitions: the way teams shape up, the tempo of a game and things like that. You can then rank the leagues against each other and build that into some of the AI modelling to benchmark players.

“You can then create a profile for a player you’re looking at and [load] all players in the world that match it. You might not know lots of these players – particularly from smaller leagues you haven’t been monitoring. As you move through the football pyramid, what teams are really interested in is value and affordability and getting players at a younger age when they have high potential and things like that. So these tools are really powerful – enabling you to get through that global football database and hone in on some players that may be of interest, which you can then take into the rest of your recruitment process.”

What to expect: Predictive data the future?

Nothing stands still as tactics and recruitment evolve. For example, the current demand for ball-playing goalkeepers and fielding players with a specific favoured foot in advantageous positions both point towards eking out advantages for passing options and avenues to shoot on goal – and data plays a huge part.

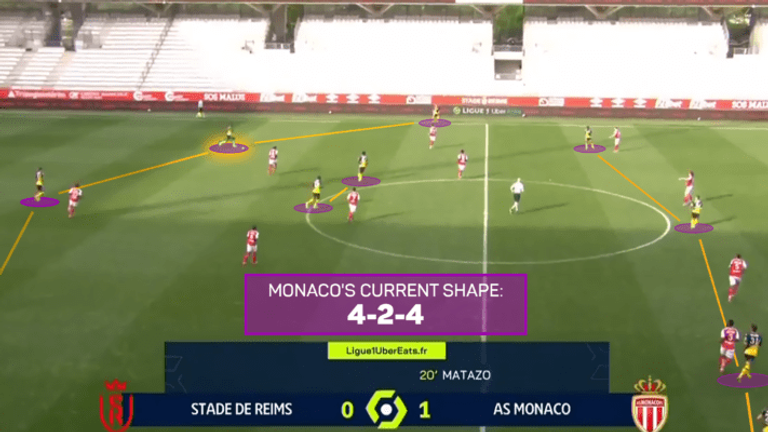

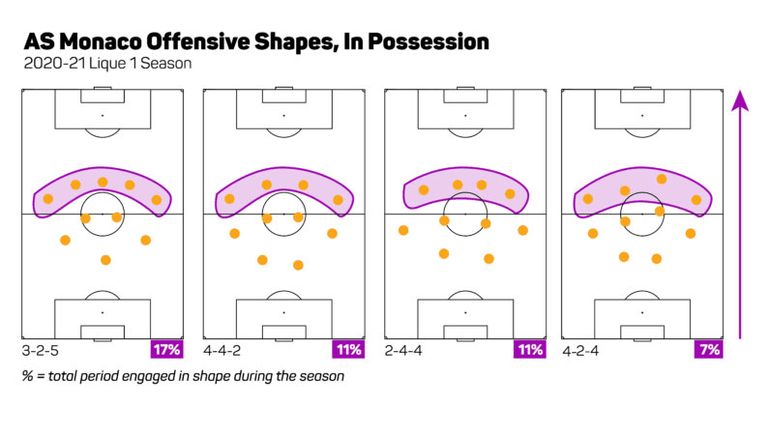

Predictive data is coming to the fore. Opta’s software presents team shapes in and out of possession – but it can also reveal where players should be positioned during phases of play, layered over where they are actually positioned. It can also quantify how different players combine and affect efficiency.

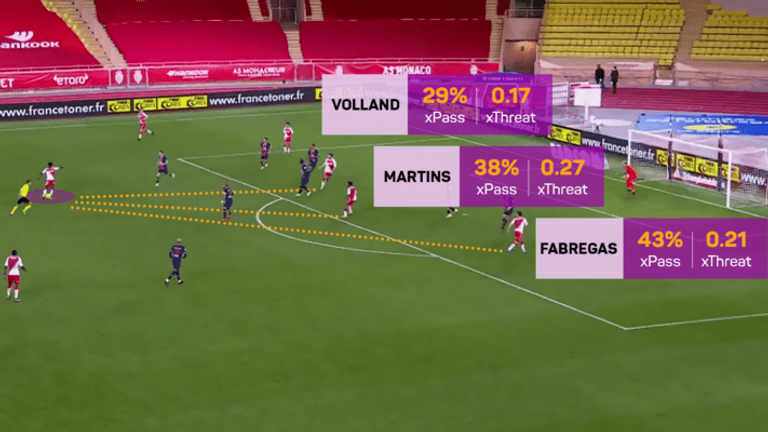

The data can already predict the likelihood of completing a pass to any team-mate at any given point and the potential attacking threat from each of those options. With these new datapoints, analysts can quantify a player’s decision-making by measuring what a player did, but also what they could and should have done. It can also reveal the proportion of time players assume different roles throughout a game.

With this level of analysis – available instantly and at scale – it appears only a matter of time before predictive data plays a huge part during games and for both pre-match and post-match analysis. As a result, players would be evaluated on how they fare against these predictive models.

Meanwhile, management teams will increasingly study how different player combinations affect overall team chemistry, both broadly and against specific opponents.

Real Analytics is another company using artificial intelligence to predict how players would perform at clubs, based on their profiles and prospective team-mates, calculating the precise impact of every conceivable starting XI against a specific opponent and on a team’s success after buying or selling a player – in terms of points and league position.

The dawn of predictive analysis appears to be under way as clubs strive and tussle to implement increasingly superior recruitment strategies.

Will contracts keep getting longer?

Arsene Wenger predicted it back in 2017. “You will see more and more players going into the final year of the contract because no club will want to pay the amount demanded,” he said. “In the next 10 years, it will become usual.”

Wenger was speaking at a time when Alexis Sanchez had merely one year left on his contract and eventually ended up moving to Manchester United in the January window with six months left on his deal.

Fast forward six years and we appear to be seeing more star players leaving clubs as free agents. Just this season, Lionel Messi, Karim Benzema, Ilkay Gundogan, Roberto Firmino and Youri Tielemans were among those who saw out their deals.

So, does signing players on longer contracts make more sense – to avoid losing the investment entirely?

Chelsea made headlines last season after their record-breaking spree included signing 18 players, with many on deals lasting seven years or more.

The strategy appears to be primarily designed to legally navigate Financial Fair Play rules, spreading transfer fees over contract terms for annual accounting purposes – a process known as ‘amortisation’.

However, UEFA is enforcing new regulations from this summer to curtail the amortisation loophole – with future fees set to be calculated over a maximum of five years. Contracts exceeding five years would still be permitted under national association rules, but the transfer fee could not be amortised beyond the first five years.

Emerging markets and disruptors

The Saudi Pro League has become the latest cash-laden playground.

Cristiano Ronaldo paved the way for elite footballers when he joined Al Nassr in December last year. Since then, players such as Karim Benzema, Jordan Henderson, Sadio Mane, Ruben Neves and Jota have moved to Saudi – with the latter pair still in their mid-twenties.

In addition to attracting Premier League stars, the Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund (PIF) has invested heavily worldwide, across diverse projects, with a bid to buy Newcastle United from Mike Ashley approved in October 2021.

The expansion into mainstream sport continued the very same month when PIF established LIV Golf, which challenged the long-established dominance of the PGA Tour.

“Oil-rich countries must diversify to become resilient to the changes in energy markets: the [shift towards greener fuels] makes economic transformation imperative,” read a bold statement published in a report by the International Monetary Fund in 2021 – and Saudi Arabia appears to be doing exactly that.

A cautionary tale?

There are lessons to be learned from previous iterations. Just five years ago the likes of Oscar, Ramires, Hulk, Mousa Dembele, Carlos Tevez and Marouane Fellaini made lucrative moves to the Chinese Super League – while Gareth Bale wanted a move there only three years ago.

The promise of bumper salaries lured players, while huge fees tempted Premier League clubs to sell. Chelsea received a club-record £60m for Oscar, who, like Neves and Jota, was in his mid-twenties at the time. In terms of the wages, Tevez was reportedly earning £615,000 a week.

But the big-money moves dried up. The big names began to leave China. Why?

The Chinese Football Association (CFA) enforced restrictions on foreign players, allowing a maximum of three permitted to play in a game. The following year, the number of foreigners permitted in a squad was reduced from five to four.

Then, a new tax was enforced, stipulating that any club buying an overseas player for £5m or more would be forced to make the same payment to the CFA. Profits, investment and, ultimately, attendances dropped.

India building sustainable growth?

The Indian Super League was founded in 2009 and has also attracted former Premier League stars such as John Arne Riise, Nicolas Anelka, Robert Pires, Freddie Ljungberg, Elano, Luis Garcia, Florent Malouda, Diego Forlan, Adrian Mutu, Eidur Gudjohnsen and Dimitar Berbatov.

In terms of head coaches, Teddy Sheringham, Robbie Keane, Robbie Fowler, David James, Anelka, David Platt, Roberto Carlos are among the travelling contingent to date. Seasoned managers such as Owen Coyle, Steve Coppell, Aidy Boothroyd, Peter Taylor, Peter Reid and Avram Grant have also taken charge at clubs in the division.

The league continues to grow and provide opportunities for overseas players and managers to ply their trade in Asia – but has refrained from the levels of spending adopted by the Saudi or Chinese leagues to date.

What about North America?

The 1994 World Cup was hosted in the USA and the first Major League Soccer (MLS) season kicked off two years later. Despite initial financial struggles, MLS has since thrived with high-profile ambassadors and signings driving engagement and attendances.

Over the years, superstars such as David Beckham, Kaka, David Villa, Frank Lampard, Gareth Bale, Thierry Henry, Wayne Rooney and Zlatan Ibrahimovic have graced the league.

Beckham launched his own MLS club – Inter Miami – after hanging up his boots with LA Galaxy. This summer, Lionel Messi joined Beckham’s side – a move which will draw even more fans, investment and attendances.

Where does the money go?

In terms of financial outlay on players from foreign leagues, Premier League clubs have typically drafted close to home in Europe’s other top-four leagues. Between 1992 and the January window this year, clubs splashed £2.52bn on players from Spanish teams, followed by France (£2.5bn), Italy (£1.8bn) and Germany (£1.7bn). Portugal, the Netherlands and Belgium have also been prominent suppliers.

Further afield, Brazil and Russia both feature in the top 10, with Argentina, Turkey and Mexico making the top 20. Interestingly, the USA ranks at No 21 with a total spend of £85.8bn to date – despite Major League Soccer being in its infancy during the majority of this period.

Excluding Europe, the majority of cash has flown to South American leagues – with nearly twice the total expenditure than Russian, Turkish and Georgian leagues combined, while North America already ranks above Asia, Africa and Australasia.

Regarding the accumulative flow of that capital, South America has remained fairly consistent, while flows to Russia, Turkey and Georgia – three countries which span Europe and Asia – appear to be in decline.

Meanwhile, fees paid to North American clubs have slowly taken a greater share of the market since the millennium, but Asia appears to have flatlined since the mid-2000s – despite the huge flows of investment into China, India and Saudi Arabia in recent years – with clubs in those nations typically buying players rather than selling them.