NEED TO KNOW

What is it? A city builder and society sim set in a frozen world

Expect to pay: $44.99/£37.99

Developer: 11 bit studios

Publisher: 11 bit studios

Reviewed on: Intel i7-9700K, RTX 4070 Ti, 16GB RAM

Steam Deck: Not Verified

Multiplayer? No

Link: Official site

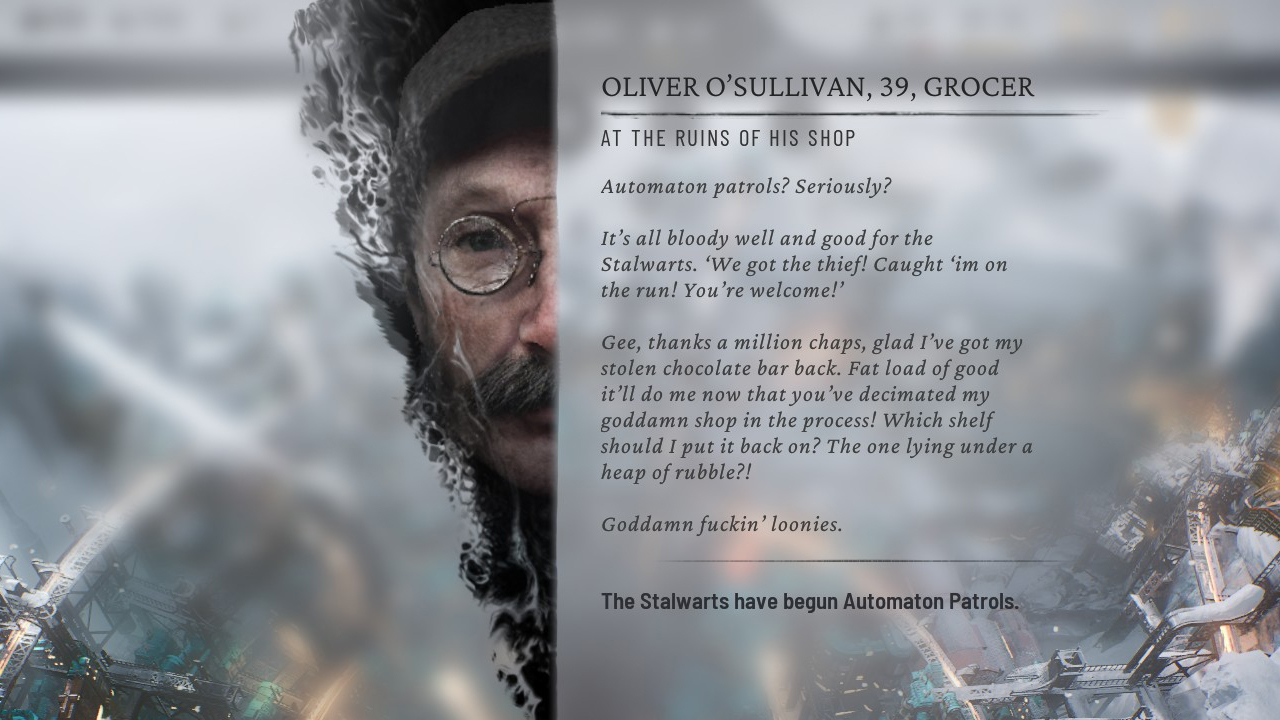

Citizens of New London: As you prepare to banish me from our city forever, I hope you understand that I always had good intentions. I never meant to run out of food, let hundreds of you perish from cold, or have the streets patrolled by giant fascist robots who stomp entire buildings flat while trying to prevent a single starving child from stealing a chocolate bar. Things just… got outta hand.

But before I step out onto the frozen tundra to die despised and alone, I would like to point out that a lot of what went wrong is, from my perspective, entirely your fault. If you could agree on a school curriculum our city wouldn’t have roving gangs of knife-wielding children. If you’d let me harvest dead citizens for spare parts you might have replacements for those eyes you lost due to working double shifts in my horribly squalid factories.

And frankly, if you hadn’t kept sabotaging my efforts to bring new technology to our city I wouldn’t have had to use quite so much new technology—like my merciless mechanized police robots—to brutally punish you. Farewell! I hate you all.

Chilly builder

30 years after the events of the original Frostpunk, the world is still freezing cold and society is still a hot mess. Frostpunk 2 is much bigger than the first game—in Frostpunk you finish the campaign with a city of maybe 800 citizens, whereas now you start out with a population 10 times that. This increase in scale isn’t entirely successful: as a city builder, Frostpunk 2 is far more abstract than the original, and I never felt much of a connection to, or interest in, my city as a physical place. As a society management simulation, however, Frostpunk 2 is just as effective as the original. It’s packed wall-to-wall with torturous choices, agonizing consequences, and a sliding scale of morality that’s slippery as ice.

Once again you’re in charge of New London, decades after it was founded and built in the original game. The breaking news isn’t great: coal, which has kept the city’s generator burning for 30 years, is dwindling. It’s time to expand the borders and harvest more materials from the frozen ground outside the city, while restlessly searching the distant frigid wastelands for entirely new resources, like oil, to keep your people alive and warm.

In Frostpunk 2 you longer place roads, houses, or single factories in your city as you expand, but lay out massive districts that can support thousands of people. Instead of a timescale of hours or days, entire weeks rush by in a matter of seconds. This transformation from the small settlements of the original game to a massive metropolis is exciting, especially visually, but it loses something in the process.

My city looks gorgeous, a sprawling network of dieselpunk pipelines, busy roadways, and fume-belching factories, but even at its slowest speed it’s like looking at a city in timelapse, which makes it feel all the more artificial. Even after hours of construction and planning, my city never felt like a place I actually built. You can zoom in on one building per district for a closer look and see a little vignette of citizens at work, but it never feels like you’re peering into a living, breathing place.

There’s still some degree of micromanagement and strategy. Harvesting the tundra means deploying “frostbreakers” to smash the ice and expose the resources beneath, which then can be harvested by building an extraction district on top. There are bonuses and penalties from certain layouts—housing does well next to sources of heat, but suffers from pollution when they’re too close to industrial areas. You no longer assign workers to buildings, but you can adjust the output of districts, which dictates what percentage of workers it will employ, letting you underclock districts if you need their workforce elsewhere.

Still, fine-tuning my districts doesn’t quite capture my interest the way most city builders do when they have a more street-level granularity to their systems. Most of the depth of Frostpunk 2 is reserved for the most challenging element of the city: dealing with the people who live in it.

[Everyone disliked that]

Influencing every action you take in Frostpunk 2 are New London’s factions and communities. You begin the game with only two or three factions in your city, but as the months and years pass the choices you make, or don’t make, will give rise to more. During times of unrest or sweeping change, smaller factions may splinter off the main groups, and while they only represent a small percentage of your population, they can still create big problems.

My city’s biggest faction was the Stalwarts: law-and-order fanatics who pretty quickly started suggesting disturbing ideas like “thought control” programs and human experimentation on prisoners—even before I’d built a prison. I also had more moderate groups like the Frostlanders, who had tried (and failed) to establish their own city outside the walls, and New Londoners who were dedicated to keeping the central generator running.

Pilgrims loathe technology so much they want me to shut off the giant generator that’s kept humanity alive for the past 30 years.

But my choice to research and implement new tech saw the rise of a group called Pilgrims, who loathe technology so much they want me to shut off the giant generator that’s kept humanity alive for the past 30 years. Hardcore survivalists called the Icebloods also appeared, extreme badasses who walk around shirtless in the cold and wrestle bears—like, for real, bears—but also think city guards should be immune from prosecution. They worry me. They all worry me.

Factions don’t just beef with you but with each other. As the Pilgrims were getting more and more annoyed with my insistence on providing heat to my citizens, they requested that I let a bunch of them leave the city to explore the frozen world outside. That was 100% fine with me—the fewer Pilgrims on my streets, the better, right? But while they were off chanting in the snow (or whatever cold-loving zealots do), the Stalwarts saw their chance to grow in power. They visited the Pilgrims’ unattended kids and indoctrinated them into their “youth program.” That made the Pilgrims even more unhappy, and I wasn’t crazy about the idea of the Stalwarts boosting their numbers with brainwashed kids, either.

Frozen gears

Getting laws passed among these conflicting factions almost always requires making deals: a group can be persuaded to vote against their interests in exchange for some consideration later, like agreeing to research a branch of technology they favor, or letting them set the agenda for the next vote. Break a promise you made, and their approval of you will plunge, sometimes so much they’ll become actively hostile and begin holding anti-you rallies, which can shut down your districts until you either start giving them what they want or send in a stronger faction to run them off. There’s a dilemma for you: should I squash the zealot community by empowering the fascist community? Spoiler: I did.

Compromising with myself was sometimes easier than compromising with factions.

That was just one of many steps I took down a darker path. Despite my semi-good intentions I slowly found myself worn down by the endless political give and take and the occasional major crisis, and soon I was making decisions not because they felt right but because they would give me what I wanted with the least resistance. Compromising with myself was sometimes easier than compromising with factions. “Okay, it’s gonna make the zealots even angrier if I pass an organ donation law, so I’ll let them have religious funerals instead. And if people need transplants… well, I’ll deal with that later. Somehow.”

Once I started betraying my own values it was pretty easy to keep on doing it. At first I scoffed at the idea of robot patrols, but then crime went through the roof and passing reasonable laws would have taken far too long and cost me more political capital than I could spend. And there was my city’s biggest and most favorable faction essentially elbowing me and pointing at a button labeled “activate giant robot cops.” Crime went down. That makes it worth it, right?

Cold logic

Other choices feel doomed from the start. Mandatory schooling for kids seems logical (especially because if you don’t put kids in school they begin knife-fighting in the streets) but what agenda should be taught? Survival classes on how to endure the cold and kill seals for meat makes sense, but don’t we as a society want to progress beyond mere day-to-day survival?

Well, how about a mixed curriculum, with some time spent on math and science and theoretical tech, and some spent on practical knowledge. Well, no, because while trying to take a balanced approach you’ve instantly made every single faction unhappy. They don’t see it as you giving them some of what they want, they see it as you denying them most of what they want. This is what you’re dealing with in Frostpunk 2. An unreasonable, angry mob that won’t meet you halfway and, quite frankly, deserves to feel the wrath of giant terror-bots at every turn.

Thankfully, I could take a break from my massive toxic city on the brink of disaster by poking my head up and exploring the world around me. The wasteland is dotted with resource nodes to harvest, frozen settlements to plunder, and tidbits of lore about what’s happened in the decades since the events of the first game. Best of all, there are larger locations in the world you can turn into proper colonies. Peel off a couple thousand citizens, send them there, and begin building housing and mining operations just like at home, though on a much smaller scale than New London.

There are huge benefits to colonization—connect your colonies and main city with trails and skylines and you can ship resources like oil, food, and manpower between them, which saved New London from outright disaster on more than one occasion. The only downside is handling the needs of one city is already a lot, and each colony is like adding another hand grenade to your juggling act. I sent those pesky Pilgrims to go colonize a new location, and they immediately began sabotaging it. God, I hate them. Maybe those thought control programs aren’t a bad idea.

Not so shockingly, on more than one occasion my “trust” meter—the constantly shrinking line at the bottom of my screen—went completely dark. Pass enough unpopular laws, break enough promises, run out of food because you were too busy tinkering with a colony instead of minding the shop, and your competing factions will finally agree on something: kicking you out of office and into the snow to die. On the plus side there are lots of ways to start over: in addition to the New London campaign, there’s a sandbox mode with seven different starting locations, different win-states to choose from, and other modifiers to play with.

As a city builder, Frostpunk 2 is a bit of a step down from the original due to the increase in scale, which unfortunately keeps the city at arm’s length. As a society sim, however, it’s every bit as engrossing as the first Frostpunk. Like a tiny snowball rolling down the side of a mountain and eventually becoming an avalanche, even the smallest choices can have major consequences.