The determination to run 1993’s seminal shooter Doom on absolutely everything is one of humanity’s finest features. From tractors to pregnancy tests, if the technology exists, someone’s trying to install Doom on it. And you know what else is technically technology? Living organisms. Yes, as prophesied in the Holy Texts, someone’s trying to get the iconic FPS running on human bacteria.

That someone is hero Lauren “Ren” Ramlan (thanks PC Gamer), a first-year PhD bioengineering student and “bioartist,” currently at MIT. On December 8 last year, Ramlan publicly posted a paper entitled “1-Bit Pixels Encoded in E. Coli for the Display of Interactive Digital Media.” In this, she laid out the history of Doom’s being run on peculiar technology, cites those who have attempted to teach cells to play Doom, and then details how she set out to use cells themselves as a pixel-like display.

Using 1,536-well plates, Ramlan set out to grow cells in specific wells, much as a digital display would light up specific pixels in order to create an image. She describes this as a “programmable display screen,” building what’s essentially a not-not gate. Using a plasmid (part of a cell) that can glow fluorescent green via a protein when not inhibited by another chemical expressed by the plasmid, and then inhibiting that inhibitor, you can—basically—tell it when to glow. This is done using screeds of differential equations that we won’t even pretend to comprehend, which was then crafted into a Python code.

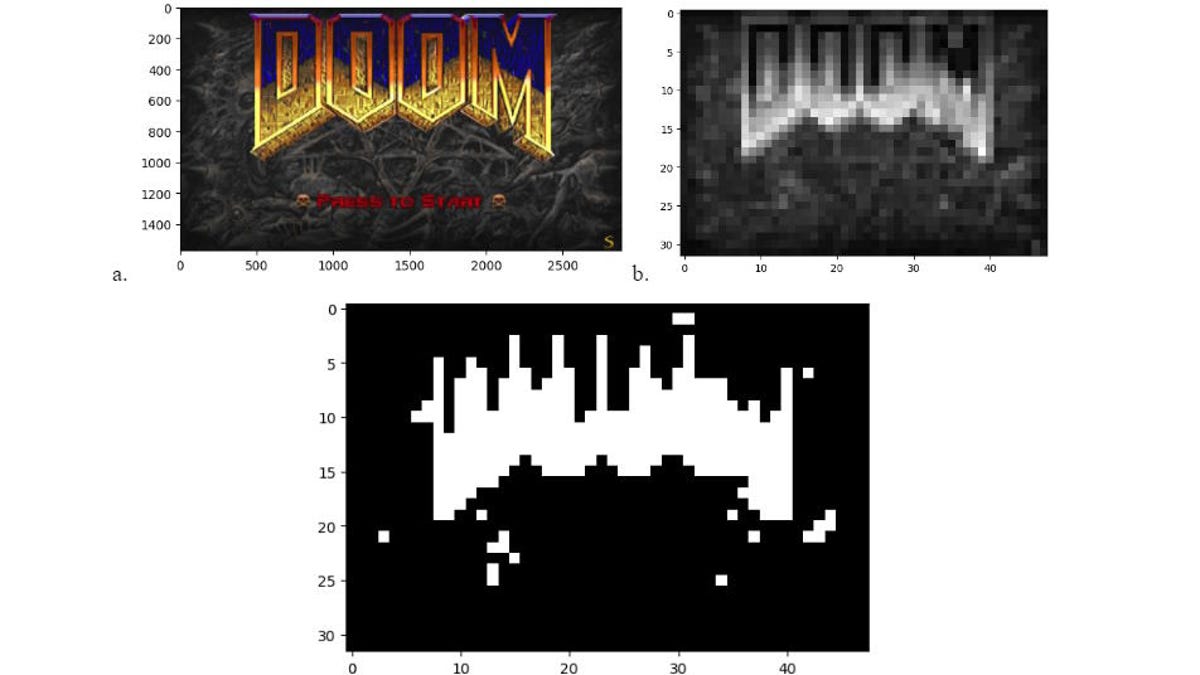

Taking Doom screenshots, Ramlan compressed them to 32 by 48 pixels, to match the cell plates, and combining the two with Science, created a system that instructs which wells to light up their cells. This is a process that takes 70 minutes to reach “peak image display,” followed by another eight hours and 20 minutes for the cells to return to their “off state.” Which is to say (by my math—please correct me if I’m wrong) a refresh rate of 0.0000292 FPS.

Lauren Ramlan concludes that running an entire game of Doom on cells would take approximately 599 years, based on its original refresh rate of 35 FPS and the game lasting five hours, which she suggests means we’re only generations away from “the peak of human engineering.”

Admittedly, right now she’s got the game’s logo to sort of vaguely appear, if you squint, and so to claim the game is actually running is a bit of a reach. However, technically, yup—it’s possible, and it kinda happened. As Ramlan points out, the design needs some improvements, especially a “memory and prediction system” that would mean pixels that would remain lit need not be switched on and off between frames.

Beat that, everyone else.