On Sept. 13, 2022, CD Projekt Red, Studio Trigger, and Netflix released Cyberpunk: Edgerunners, an anime series based in the same world as CDPR’s 2020 video game Cyberpunk 2077. The rough initial state of 2077 left potential Edgerunners viewers cautious, and the trailers seemed to promise an edgy, ultraviolent action anime with more in common with Ninja Scroll than Perfect Blue.

A year out, it’s almost silly to think about anyone having been cautious about the show. It’s 100% fresh on Rotten Tomatoes, was an Annie Award nominee (a relative rarity for anime), and outright won Anime of the Year in Crunchyroll’s Anime Awards. It is, by all accounts, a masterpiece. Not only that, but it ended up being a pitch-black, razor-sharp satire of the dark future we’re hurtling toward, and an especially important one to revisit with the release of Cyberpunk 2077: Phantom Liberty.

One could be forgiven for thinking the show’s satire would be shallow, given how heavy-handed the show’s parallels of current issues are early on. We first meet David Martinez, the protagonist, when he’s informed by his washing machine that he can’t wash his school uniform unless he pays a fee. His mother, Gloria, is exhausted by a night-shift job that leaves her and David with barely enough to survive, in a dirty, cramped apartment. David’s school is a privatized, megacorp-run charter school that gives him seemingly AI-generated lessons. And, near the end of the first episode, David finds himself trapped in an overturned car, watching his mother bleed out on the asphalt as paramedics walk right past her; she’s uninsured, so the “medical care” she does receive kills her.

[Ed. note: The rest of this post contains spoilers for Cyberpunk: Edgerunners.]

When David bursts into the local ripperdoc’s office holding a stolen piece of blood-drenched cyberware from a crime scene, shouting “high time I chrome the fuck up,” viewers might be primed to expect a series about him rising up and fighting the system. The Hunger Games (soon to receive a new film installment itself) isn’t a story of Katniss Everdeen getting crunched into dust. Same with Divergent or The Maze Runner, or the original Star Wars trilogy and nearly everything that copies its template.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24016192/Edgerunners_001.jpg)

Image: Studio Trigger/Netflix

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24016181/Cyberpunk_Edgerunners_Season1_Episode3_00_11_24_03.jpg)

Image: Studio Trigger/Netflix

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24019402/Edgerunners_006.jpg)

Image: Studio Trigger/Netflix

The typical format for these stories is a Campbellian hero’s journey against a corrupt power structure, and Edgerunners doesn’t do much to disrupt that in its first third. The characters in Maine’s gang fit into the usual archetypes: Maine and Dorio settle into the roles of David’s mentors; Lucy becomes his love interest; Rebecca, Pilar, and Kiwi are the “cool ones.” There’s an initial job with them to get David acquainted, and then a montage of David getting stronger and more familiar and competent, as is typical. Astute viewers may notice foreshadowing even this early on, however — David’s Sandevistan, his cybernetic edge, is depicted as something deeply harmful to him (and the process of getting more cybernetics is shown as a horrific surgical meat grinder).

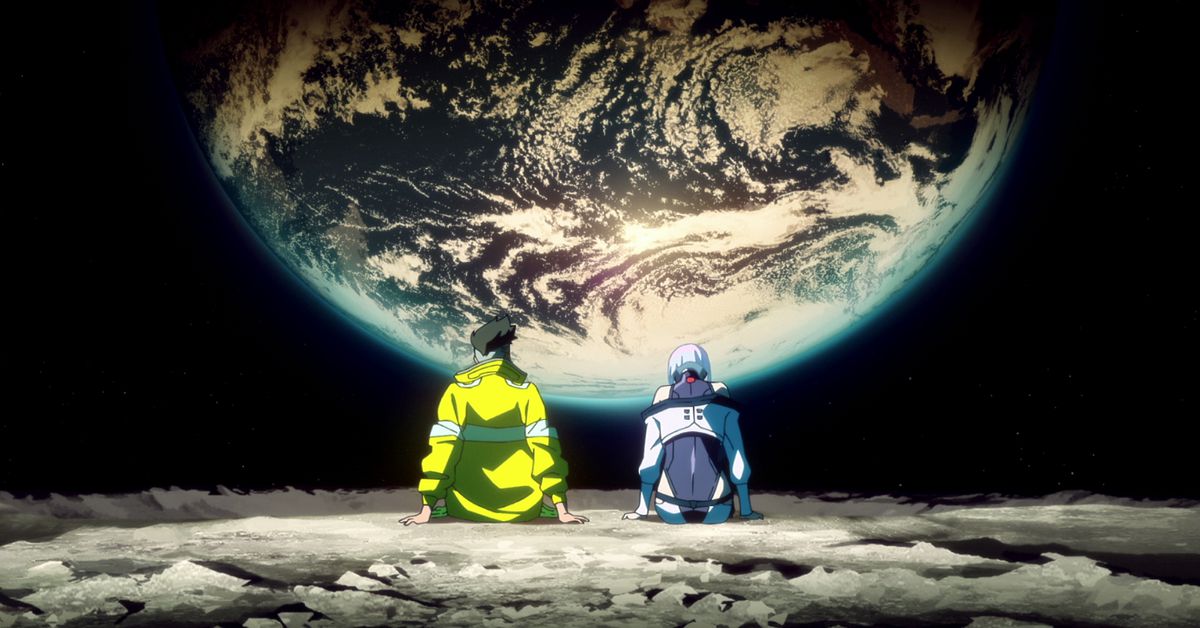

In the second half of episode 4, however, things take a decisive turn. Pilar harasses a man urinating off the edge of a cargo container and unceremoniously gets his head blown off; the gang isn’t even given time to grieve until after a brutal fight. Rebecca, Pilar’s sister, mourns by unloading yet more ammunition into the corpse. The scene cuts to David and Lucy going for their nightly run, stopping on a rooftop and having a heartfelt conversation where Lucy directly tells David, “You don’t make a name for yourself as a cyberpunk by how you live; you make a name by how you die.” David affirms that he wants to be one, regardless, just to be with her. They kiss, a rocket launching behind them in the frame, as Dawid Podsiadło’s “Little Stranger” crescendoes.

It’s a beautiful moment. One of the most beautiful in the series, in fact; the show’s visuals trend toward the hyperactive and nightmarish, in keeping with the setting, but it pulls back and allows moments to breathe when David and Lucy are together. One of Edgerunners’ key strengths is its ability to let its visuals tell the story; prior to this, one might notice that the opening credits end with a shot of a silhouetted man standing over a dead David, holding a smoking gun, images of the city visible through him. While that stands as the show’s most basic thesis statement, the end of episode 4 is where it starts to get blunt: This is not a story that’ll end happily.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24017381/Edgerunners_048.jpg)

Image: Studio Trigger/Netflix

Things continue uneasily for the show’s middle act. A braindance editor captures David and asks him, directly, what makes him any different from the many and sundry cyberpunks he’s seen (and filmed) dying horribly; David’s answer, that he’s simply built different, isn’t a satisfying one. The long-term job they’re on, a kidnapping of an Arasaka employee named Tanaka, wobbles, as Maine loses control of himself. Then, in episode 6, Maine and Dorio die, leaving David in control of the gang.

The first act of the show establishes the setting, and the second act hammers in, as much as possible, that this is not going to go well for anybody. And so the death spiral begins: Over the course of the remaining four episodes, David is slowly torn apart by his cyberware, and the crew begins to splinter and fracture. Kiwi turns on them, selling them out to Arasaka. David’s quest doesn’t end with him taking down Arasaka and making a better world; it ends with his mind completely shattered by an experimental “cyberskeleton” he’s used as a test subject for, and a hole blown through his head after that experimental tech gets destroyed (plus witnessing the death of nearly every member of his crew).

The show’s message is clear: The people who look at politics in terms of Harry Potter or Star Wars or The Hunger Games are fundamentally wrongheaded. There will not be a Luke Skywalker or Katniss Everdeen rising up to stop fascism and heroically save us all from the encroaching destruction of human civilization. Mike Pondsmith, the creator of the Cyberpunk tabletop role-playing game, isn’t interested in stories of heroes and happy revolutions like that; instead, he’s guiding us through the Inferno we’re heading toward, and Edgerunners is the most accessible and faithful representation of his 35-year-running Divine Comedy yet. If things actually get to the kind of dystopia depicted here, the best humanity will be able to do is a David Martinez, and he’s more likely to end up bleeding out on the asphalt than saving us all. The franchise leaves what to do and how as an exercise for the viewer, but what’s clearly visible in Edgerunners is this: We need to fight for something better now, not later.