In its 28th year of showcasing films at the Chicago International Film Festival, the Black Perspectives Program has put archival classics back on the big screen, giving them the ability to impact new audiences in new ways. With the power of 4K restorative technology, meaning the visual and audio of a film are remastered and significantly enhanced, movies receive a second life and sometimes a second run in theaters. For works by Black filmmakers, restorations and digitizations mean permanence in the archive and inclusion and proper recognition within the broader moviemaking canon.

The restored “Compensation” is overflowing with romance, poeticism, innocence, and heartache. Director Zeinabu irene Davis proudly boasts that the restoration of her 1999 film is actually a “rejuvenation,” with additional accessibility elements such as closed captions and enhanced sound. As the revitalized film recirculates, there is also regenerative representation for non-hearing individuals. The Black community to independent filmmakers to those battling autoimmune illnesses will all be able to resonate with reflections of themselves on screen.

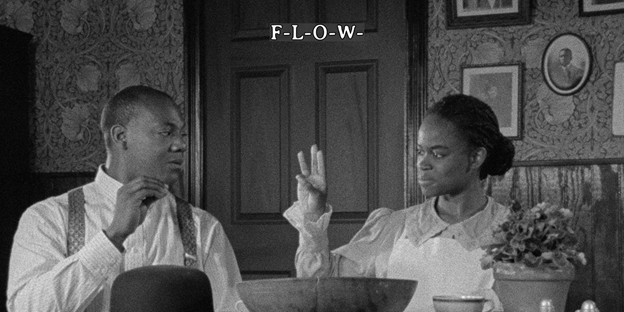

Originally shot on 16mm black and white film, the restoration manages to keep all of the warmth that comes with celluloid. As the film oscillates between the tale of two lovers in the 1900s and the 1990s, there are key connective points in each plotline: a trip to the movies, laughter in learning, and sweet nothings whispered in American Sign Language on the shores of Lake Michigan. Davis and crew strategically utilize archival photos sourced from the Chicago History Society to transport the audience to progressive-era Chicago. Costume design and title cards are the cherry on top for making the period piece sequences of “Compensation” immersible and believable.

Titled after and inspired by the Paul Laurence Dunbar poem of the same name, which also appears throughout the film in songs and love letters, Davis, alongside the film’s composer, ragtime pianist Reginald R. Robinson, screenwriters, and the cast, create an exceptional independent picture about commonly taboo topics. Interconnected issues of race and gender are explicitly evident, but “Compensation” embraces the theme of ability and ableism with a copious amount of care while also enacting its motif of the power of education.

Based on Sam Greenlee’s 1969 novel, “The Spook Who Sat by the Door” is an explorative, calculated adaptation. The Chicago-set story, directed by Ivan Dixon, is amplified by a clever, witty, inspirational script, suave ’70s fashion, and tactful action-forward sequences. At the onset of the film, we witness the superficial efforts of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to become more diverse after a politician runs on the basis that the CIA is exclusionary to boost the Black vote in his favor. As the CIA attempts to avert these claims, they enlist just one Black agent. From the onset of the film, it’s unequivocally clear that those in power care only about the optics; there are no true allies on the inside.

Gil Scott-Heron’s song “Whitey on the Moon” kept running through my mind throughout the CIA training process and as the protagonist, Dan Freeman, phenomenally played by Lawrence Cook, returns home to train guerilla troops. “You cannot cage an animal and expect it to not fight back one day,” Freeman states as one of the many reasons he returned radicalized with purpose and a plan. At the time of its debut, “The Spook Who Sat by the Door” was easily pigeon-holed by Hollywood as another “Blaxploitation” film; with this rerelease, it has the opportunity to rectify its place in the archive as a sophisticated, call-to-action drama that leaves the audiences questioning who gets to live the American Dream versus the American Nightmare.

Read more about “The Spook Who Sat by the Door” in this feature by Robert Daniels.

“It happened in Chicago, but it could’ve been anywhere.” Stan Lathan’s 1973 film, “Save the Children,” documents Reverand Jesse Jackson Jr.’s 1972 Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity) and the PUSH EXPO, where the Black community gathered and rejoiced in their contributions to history and culture while also setting their sights on what it will take to be successful in the future. The exposition built around the theme of “save the children” brought together Black businesses, artists, musicians, community constituents, and leaders. Despite exhibiting multiple industries, focusing on providing educational tools to the Black community, the “Save the Children” documentary, now available on Netflix, only showcases the powerhouse musical performances and the occasional speech from Rev. Jackson.

In its 99-minute runtime, contemporary audiences can experience intimate performances from Marvin Gaye, Bill Withers, the Jackon 5, Curtis Mayfield, The Temptations, Roberta Flack, and many more. The film’s brief voice-over introduction is the only informational crutch that supports audiences’ understanding of the symposium’s diversity and purpose. PUSH EXPO was a full five days of programming on Chicago’s South Side; to be classified as a concert film is a disservice to the array of activations to uplift the Black community. However, joy and excitement are abundant as the camera pans to the crowd, singing, swaying, and smiling. To the filmmakers’ credit, one must acknowledge that “Save the Children” was saved from extinction; sourcing the original footage and audio was quite the feat, hence the focus on including the best performances and speeches. There are also balancing moments captured as the camera rolls through the streets, shining a light on both the beauty and hardships that the community faces. In these moments, the viewer is reminded that this is not simply a music movie; it is the footage that keeps a legacy alive.

Like “The Spook Who Sat by the Door,” the authentic, psychedelic fashion of Black folk in the 70s saturates the screen with immense color that matches the vibrancy of the music we hear. As the film concludes with a sermon from Rev. Jackson, the crowd is left with a feeling of empowerment, yet the film’s audience is left wondering: what happened to PUSH EXPO?