Need to know

What is it? A dream-diving visual novel where you solve a murder mystery in near-future Tokyo.

Release date: Out now

Expect to pay: £50/$60

Developer: Spike Chunsoft

Publisher: Spike Chunsoft

Reviewed on: Intel Core i7-10750H, 16GB RAM, GeForce RTX 2060

Multiplayer? No

Link: bit.ly/SomNirvana

Jin Furue has been murdered. Someone has sliced the CEO in two and left one half at a TV studio, where a quiz show is being recorded live. The other half of Jin won’t show up until six years later, having seemingly died just a few hours earlier. That’s the baffling setup for AI: The Somnium Files – nirvanA Initiative, an out-there anime visual novel, but with a compelling murder mystery at its core.

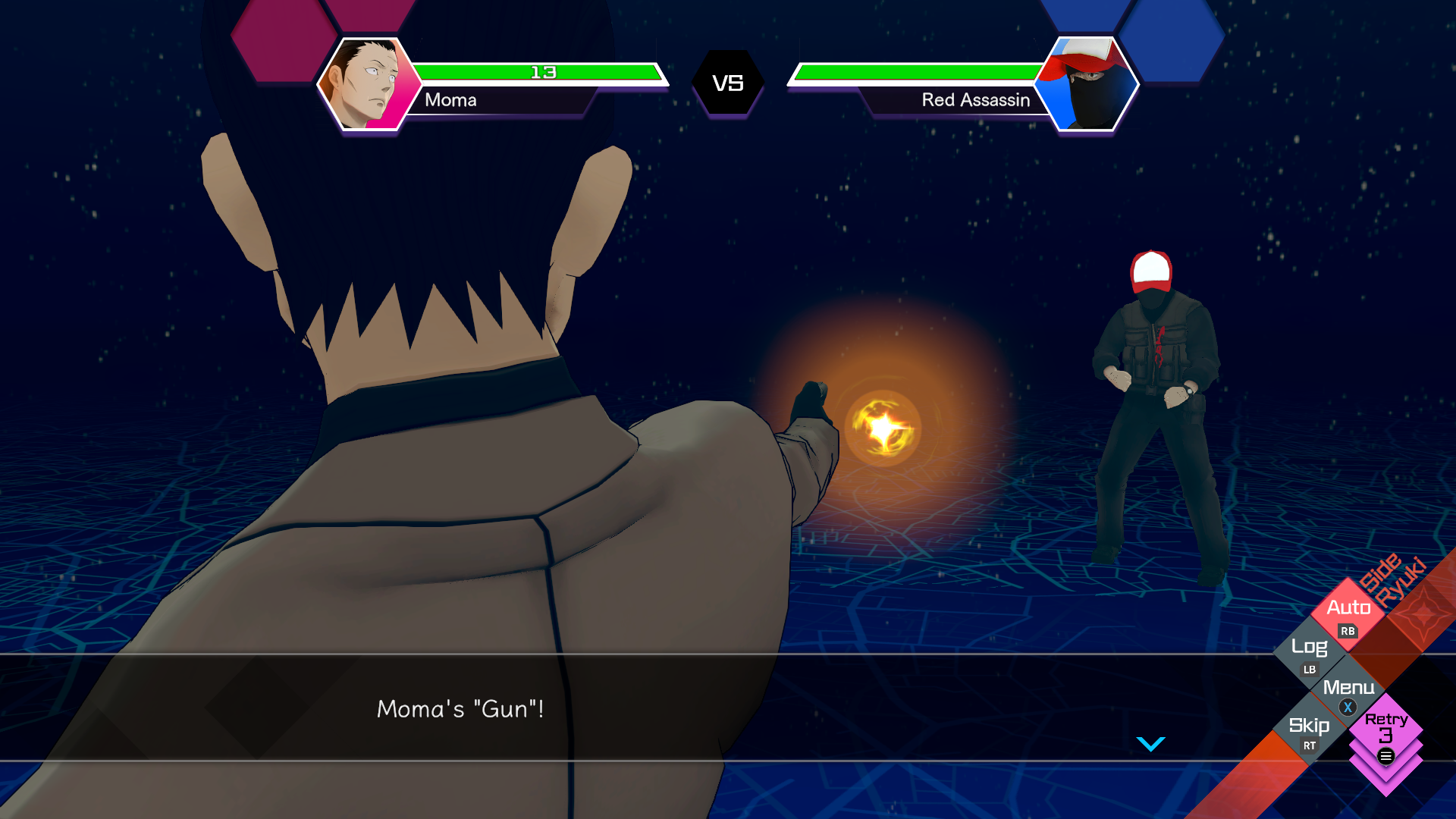

You’d be forgiven for thinking otherwise, given how bonkers this sci-fi adventure can get. Your constant companion—at least for half of the game—is a smutty artificial intelligence who lives in a fake eyeball where your left eye should be. With her help, you’ll solve the mystery of the Half Body Serial Killings while swatting off conspiracy theories, creepy viral videos, and a cult that believes the world is a mere simulation. That is, when you’re not battling faceless goons to quick-time prompts in one of a handful of preposterous action scenes.

Like its predecessor, Nirvana Initiative is a sprawling mystery that touches on multiple genres, mixing visual novel conversation with the aforementioned action bits, and more interactive scenes of puzzle-solving and investigation. Somehow, it all gels together—this generic fusion and the conspiratorial sci-fi—because it doesn’t take itself entirely seriously. You’d be surprised by a Pokémon minigame in the latest Frogwares Sherlock Holmes adventure; here, it’s just another day at the office.

Set in a near-future Tokyo, the Somnium Files games concern a department of elite, high-tech cops who use those aforementioned eyeball AIs to help them solve perplexing mysteries, with their real eyeball being surgically extracted. But this shuddering act of mutilation does come with an upside: with the AI ensconced in their ocular void, the agent is able to view stuff in X-Ray or thermal vision, and walk around in nifty VR recreations of crime scenes.

For the first half of the game, you play as the mentally unstable special agent Riyuki, whose mind unravels as the case takes its toll on him. After he fails to find the culprit, the story jumps forward by six years and into the shoes of a superpowered high-schooler named Mizuki, who is put onto the case after Jin’s left half mysteriously reappears.

Both agents—thanks to those AI-balls—can not only use X-Ray vision to see under a suspect’s skin, they can also ‘psync’ with their unconscious minds: a horrible contraction of a word, but one that at least has the decency of a silent P. Psyncing is essentially entering dreams, a la Inception. You can do a quick ‘wink psync’ when interviewing suspects, snatching a brief glimpse of their minds when the game allows. But the tent-poles of the game are full-fledged psyncs performed back at the lab, where both detective and subject are hooked up to a special machine.

Psync or pswim

While much of the game plays out as a traditional, dialogue-heavy visual novel—or a light adventure game as you examine scenes—psyncs are more reminiscent of JRPG dungeons. Controlling your character in third-person, you’ll explore environments drawn from the subject’s subconscious, with their innermost thoughts and feelings manifesting themselves. One character’s dream takes the form of a twisted quiz show, for example, while another is a fun and vibrant Pokémon parody. In effect, they’re pretty similar to Persona 5’s mental dungeons, but with a focus on puzzles and a strict time limit, which ticks down with every action you take.

You’re trying to open mental locks to ultimately reveal a hidden truth and hopefully a clue related to the murder case. However, every action, even walking, consumes precious seconds. Standing still effectively pauses time, giving you a moment to think and to weigh up your options. How will hurling this briefcase, or slapping the subject, or putting a shoe in this box open the next mental lock? But as random as the actions sometimes seem, the game justifies their connection to the subject’s mind. Take a moment to think things through, or risk wasting so much time that you have to restart from a previous checkpoint—and on the default difficulty setting, you’re only given three retry attempts.

I enjoyed the tension during psyncing, but there are ways around it if time limits bother you. You can tinker with the difficulty, or just reload from a manual save when you run out of time. Still, I’d urge you to give it a go as is, as it’s a clever way of asking the player to actually think about the puzzles, rather than barging their way to the solution through repetitive trial-and-error, as I do in pretty much every adventure game.

These mind-exploring dungeons might be the focal points of Nirvana Initiative, but my favourite parts of the game are more understated. After each new murder—and there are quite a few of them—you’re plopped down in a swishy VR version of the crime scene. It’s here where you feel most like a proper detective, running up to the evidence and examining it directly (your X-Ray/thermal vision helps) while chatting theories with the AI nestled in your eye-hole.

Those might be the best bits of traditional murder mysteries: the moments when the sidekick posits fanciful theories—theories the readers themselves will doubtless be thinking—before the great detective shoots them down with an arched eyebrow. Well, Nirvana’s VR crime scenes are where those moments are recreated here, with the player taking the role of the sidekick, and the great detective being played by the AI.

But as happy as I was investigating the crime scenes, they’re fairly limited in scope, being both small and annoyingly inflexible in their conclusions. You’re quizzed at the end about what you’ve learned from each scene—basically about what the AI has hinted to you—and you can’t progress, or do anything else at all, until you supply your AI pal with the correct answers. I know this is a (largely linear) visual novel, and not a more freeform detective game where you’re allowed to come to incorrect conclusions, but it’s still an irritating way to present puzzles.

Friendly fire

Not that I’m knocking the visual novel sections—these were the moments that gradually sucked me into the game, acclimating me with its outlandish cast. Nirvana Initiative treats its suspects very differently from traditional murder mysteries, which typically keep their shifty casts at a remove. After all, Poirot is an unwelcome outsider in whatever country house he is currently investigating—as a detective, it’s his duty to ruffle feathers and shake hornets’ nests. By contrast, here you’re one of the gang. Many of the suspects come to be friends over the course of your investigation, if they’re not already at the start of the game, and detectives Riyuki and Mizuki are the glue holding them all together. The interviews don’t feel like interrogations, most of the time, but more like friends hanging out and chatting about the case.

Rather than suspects, they feel like party members in a JRPG—memorable characters brought to life with a sharp script and excellent voice acting. I wouldn’t say I like most of them—around half of the cast is annoying or creepy (although at least the script acknowledges this), and I remain frustrated by one character’s inexplicably cube-shaped head. But, as the hours passed, I came to enjoy being in their company.

Now, that might be Stockholm Syndrome talking, but I think it’s due to the quality of the writing, which walks a fine line between smutty and straight-faced, silly and emotional. As much as that cube-headed fella frustrated me, the subplot with his introverted son is beautifully told.

Sometimes you forget you’re playing a murder mystery—a meaner word for that might be ‘padding’—but there are benefits to making you care about this cast of suspects. These emotional subplots only make it more effective when the killer does come knocking again.

I said that the game was largely linear, and that’s because of the multiple endings, which branch off from infrequent diversions made while psyncing. There aren’t that many branches, but they’re used in fascinating ways, bringing certain subplots to a close without you determining the identity of the killer.

In any other game those would be the bad endings, but they can be weirdly happy here, providing NPCs with satisfying endings at the expense of the overarching mystery. Return to a previous chapter, in order to diverge down the ‘true’ path, and those touching conclusions may never happen. Sure, as a result you’ve solved the mystery of the Half Body Serial Killings—but at what cost?

With its branching paths, and its two time periods, the game does feel drawn-out, however. I ultimately came to groan whenever I knew a psync was coming, as that would be another half-hour added for no good reason. Oh, there are flimsy excuses given for the subjects’ refusal to share information, but this is a story that sometimes feels baggy and overlong.

I didn’t mind that too much though, in a game that mixes genres with aplomb, and that holds onto its central mystery even as it indulges in conspiracy theories and dream-state weirdness. It’s a philosophical sci-fi story, but with clear limits to its future tech, and ultimately reasonable explanations for its impossible crimes. Above all, this is a game that respects the art of the detective story, and that does a decent job of presenting its own.