NEED TO KNOW

What is it? You are Judero, a warrior-Druid putting right what has gone wrong in Scotland.

Release date September 16, 2024

Expect to pay $18

Developer Talha and Jack Co.

Publisher Talha and Jack Co.

Reviewed on Steam Deck

Multiplayer None

Steam Deck Unverified (but works well)

Link Steam

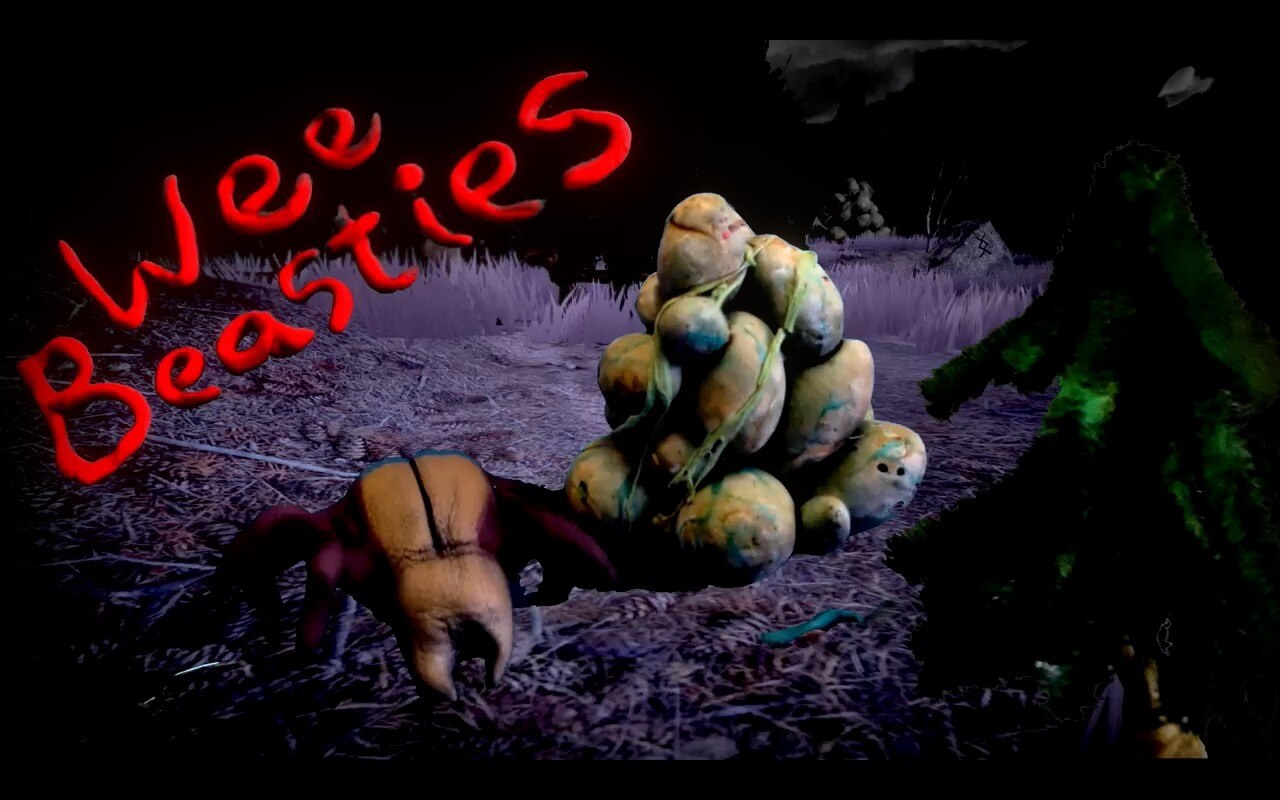

Strangeness and eccentricity can often feel like an affectation, so I cherish it when a game is genuinely one-of-a-kind. Judero could have only been made by Talha Kaya and Jack King-Spooner, two independent developers who crafted a vision of the Scottish Borders entirely out of action figures and modeling clay, a game with the kind of rough edges and pleasant surprises that could only come from a genuine artistic vision.

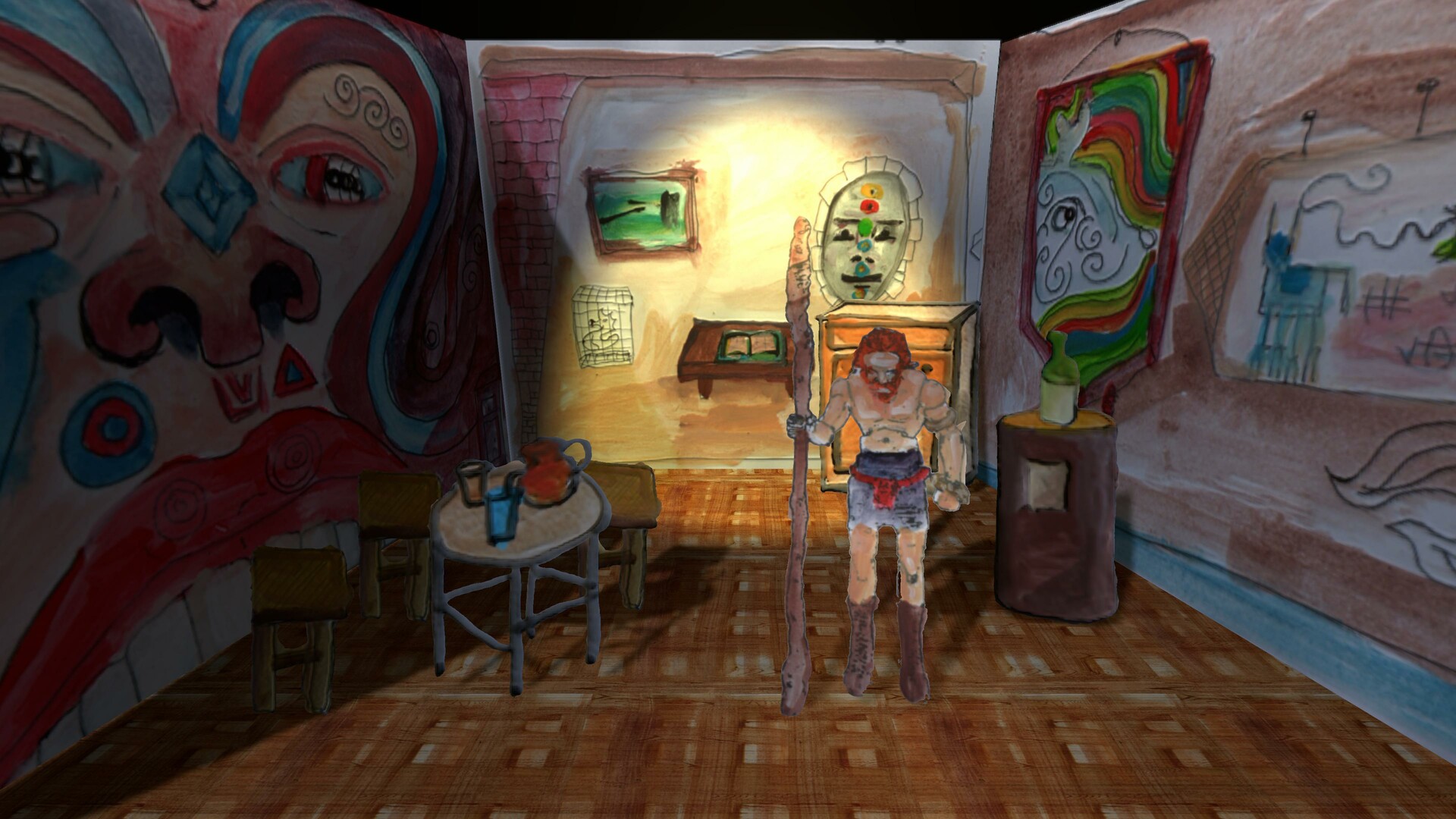

Judero casts you as the titular Judero: a rough-hewn warrior-priest clearly made out of Milliput and an old GI Joe action figure. He cuts an imposing figure, but he’s actually a very thoughtful, open-minded guy: One defining early moment of the game begins with the jumpscare-adjacent, discordant introduction of a clearly evil witch, then cuts to her and Judero having tea and discussing the townsfolk’s mistaken impression of her.

Judero is an indie’s indie game, made by two guys with most of the rest of the credits taken up by their family, friends, and Kickstarter backers. Like this year’s Harold Halibut, Judero uses real, physical models for its digital assets, with full-on stop motion in its cutscenes while the gameplay uses sprites in full-3D environments like the original Doom. The music is also a real treat: acoustic guitar-driven folk tunes that set a nostalgic mood and dovetail with Judero’s pagan, earthy influences.

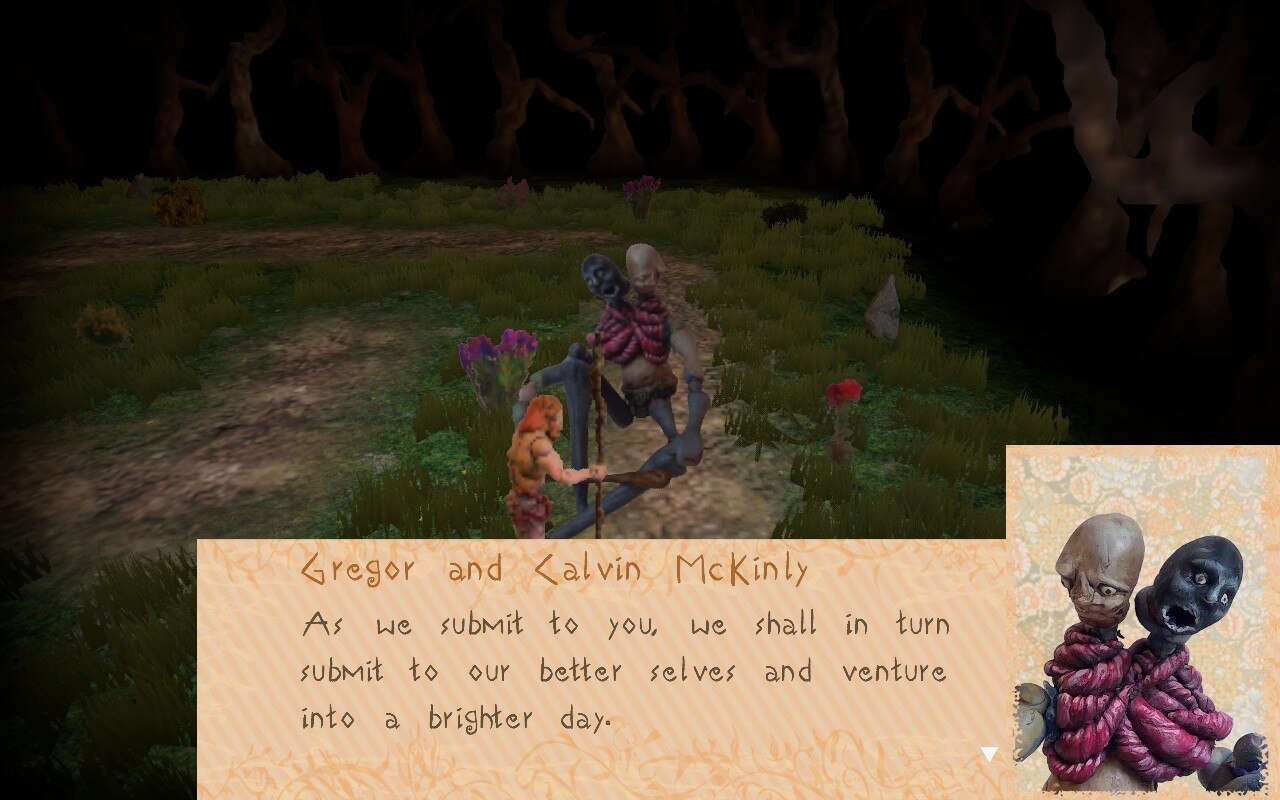

The result of Judero’s unique building blocks looks like the Last Voyage of Sinbad but even more deliberately uncanny: The characters are all misshapen and rough-cut, with bulging eyes and cratered flesh, but it’s somehow not a horror show. Like so many classics of stop motion animation, Judero’s characters are unsettling but not unpleasant, ugly-cute and moving in that off-putting, jerky claymation way. That charm is bolstered by Judero’s writing: Co-creator Talha Kaya wrote that the duo “hid a bit of humanity around every corner” and I absolutely felt that while playing.

Friend-shaped

Late in the game, one of those goggle-eyed clay NPCs I love so much recalls a strange saga wherein they forbid their lover from entering a locked wing of their shared home—not to protect a secret, but in a desperate attempt to seem like the sort of person who might be interesting enough to have secrets. Every townsperson in Judero will wax poetic about their strange, surreal, or tragic lives in beautiful, moving prose, and one of my favorite parts of the game was just wandering through each village, speaking to every single NPC. There’s no “I hear the Fighter’s Guild is recruiting again” filler to be had: Everyone has something to say, usually in multiple parts.

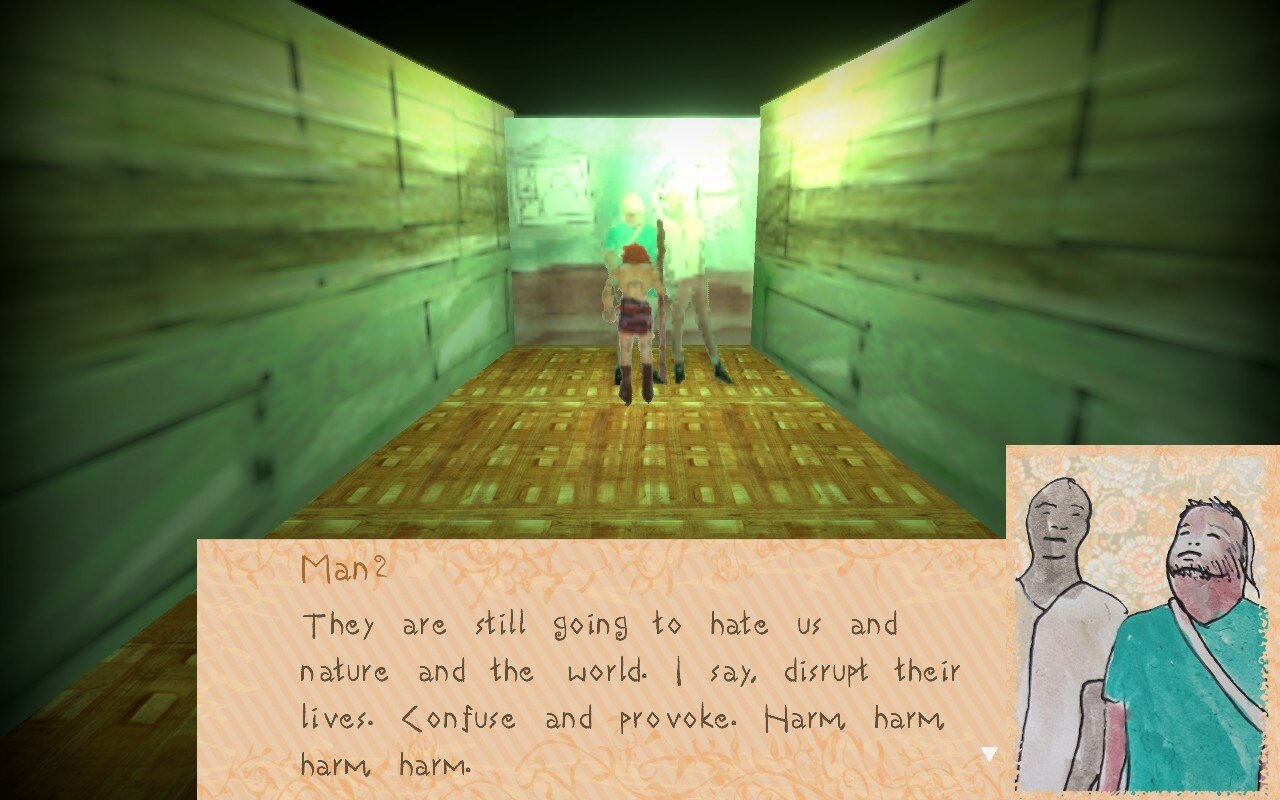

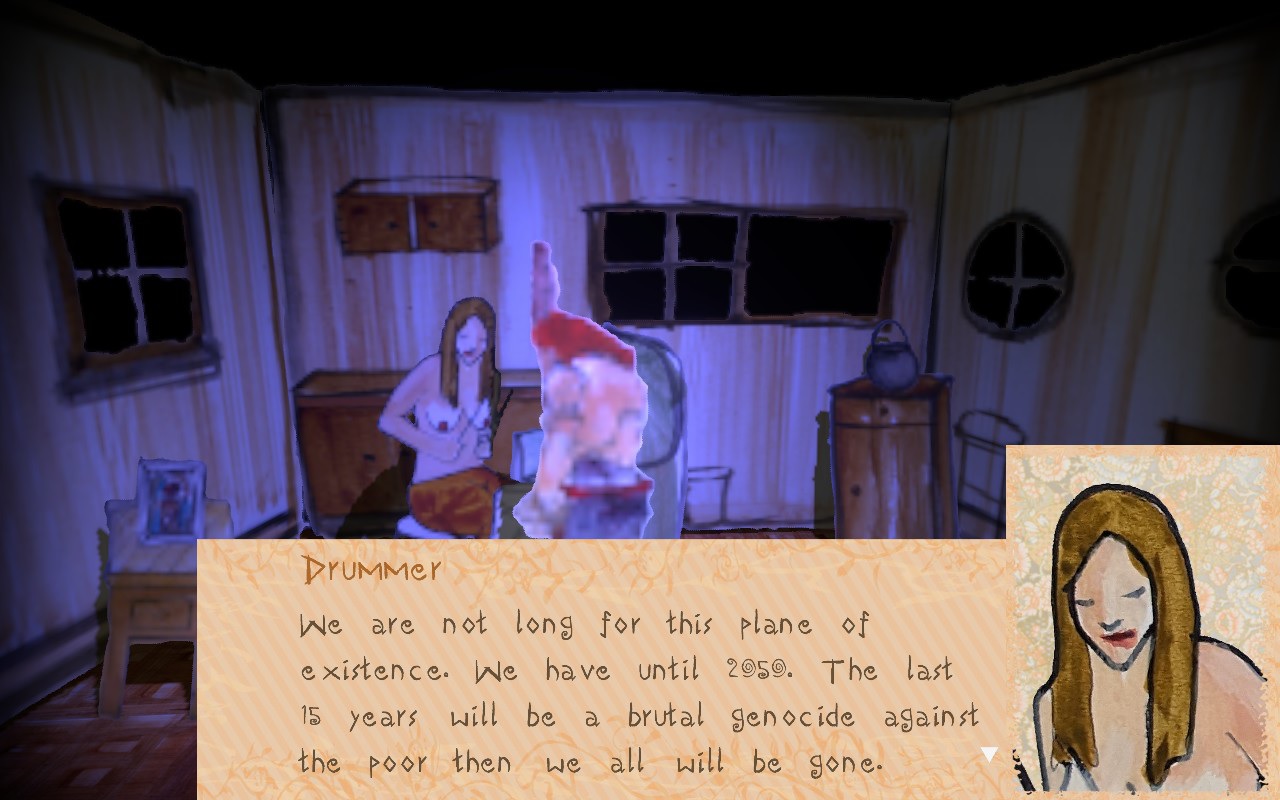

When you enter houses in the towns, the art style shifts to dreamy, vibrant watercolors, with even Judero replaced with an impressionistic stand-in, and the residents inside often seem unstuck in time. In the second village, a pair of lads in T-shirts and shorts ruminate on the merits of ecoterrorism in a world sleepwalking toward destruction: “We aren’t trying to get those people to love us. We have learned a sad lesson, that nobody loves this world.” In a neighboring building, a shirtless drummer extols the virtues of the divine feminine and predicts that the world will end in 2050: “The last 15 years will be a brutal genocide against the poor then we will all be gone.”

Despite the sharp political cast of some of its digressions, Judero never felt ham-fisted or polemical—the anachronisms hit me like a stiff breeze or splash of cold water, showing up with no introduction or explanation and making me do a double-take. Judero presents its big ideas thoughtfully, wrapped in the general surrealism of the whole experience, often in optional nooks and crannies. Its philosophical musings and open-ended side stories are going to stick with me for a long time.

Lest that sound too boring or high-handed, I can vouch that this is also a very funny game: While most enemies are mythological abominations, partway through the game, Judero finds himself fighting “Men from Carlisle” (an English city bordering Scotland) who inexplicably shout “Carlisle!” over and over like Pokémon. Towards the end of Judero, one Simpsonsesque heater of a line had me laughing so hard my girlfriend came over from the other end of our apartment to see what the commotion was: “The hallucinations are getting more vivid,” Judero muses while lost at sea. “Thankfully my talking ape friend has been keeping me sane.”

Staff and sandals

Gameplay-wise Judero is an odd mix, with its digressions into different styles and perspectives reminding me of the NieR games. It also has the same core as NieR: hack n’ slash brawling and bullet hell projectile dodging.

That melee combat is easily the weakest part of the experience: It has poor feedback in general, with hits on enemies feeling weightless, the perspective often making it a chore to line up attacks, and many enemies having aggravating, multi-part attacks that can stunlock Judero and eat through his health bar. At its best, the brawling is adequate connective tissue: Another thing to do while you wander over hill and dale.

What’s frustrating is that every other aspect of Judero’s gameplay is much stronger, particularly its bosses and their screen-filling projectile attack patterns. One late-game fight in particular really scratched the same itch 2016’s excellent Furi did for me: A duel with a forest goddess and her lover in the skies above a magical island. Instead of bashing them with Judero’s walking stick in between attacks, you have to dash around activating magic sigils on a timer. Fights like this could be thrilling, and I wonder if Judero would have been better-served embracing twin stick shooting instead of melee combat, or otherwise excising the attack option entirely in favor of dodging and puzzle solving.

Judero’s possession mechanic might have helped fill the gap. Judero can use his druidic magic to possess enemies and bypass obstacles, sort of like the enemy stealing in Mario Odyssey. The mechanic has moments of real brilliance, like a boss fight where you have to possess an insect and climb down the monster’s throat, reaching crucial viscera at the end of a nasty, faux-3D tunnel run and eating the thing from the inside. Most of the possession puzzles throughout the game are a bit simplistic, but then there’s a rush of more challenging, intricate ones right at the end. I found myself wishing those brain ticklers had been better spread throughout the game—squashed together all at once as they are, they turn into a bit of a slog.

Even with those complaints, Judero has a real capacity for surprise and whimsy in its mechanics, catching me off-guard in a similar way to its conversations. One of the highlights is the setup of its third act: An open-ended archipelago you can sail around and explore in any order, complete with optional dialogue and a positively delightful poetry reading from your passenger, that talking ape friend I mentioned earlier. I activated act three’s point of no return a bit early and probably left some exploration on the table, but the whole thing’s a delight, full of oddly-shaped and completely optional islands to explore, as well as more of those NPC conversations I love.

Performance-wise, Judero’s about as lightweight as they come and even runs fine on Steam Deck, though installing it to my SD card instead of the hard drive resulted in some pretty sluggish load times, particularly in that open ended sailing section. That’s something to keep in mind if you’re considering this for Deck or are still rocking an HDD for storage on your desktop.

Judero is the kind of indie game that’s really worth celebrating. It’s funky and has some rough edges, but that comes with the territory for such a unique labor of love. Judero isn’t a transcendent action game or a next-level puzzler, but those aspects are good enough to support its real draw: a thoughtful, strange world and incredible aesthetics.