I was just young and naive enough when The Blair Witch Project came out to be suckered in by the premise that it was real—that someone had found this real life footage after the fact, or that it was just a movie but one based on real events. Even now when you Google it, the first “People also ask” result is: Was Blair Witch based off a true story? After 20 years of horror movies aping that gimmick, the Google doc that accompanies Doom mod Myhouse doesn’t really have a chance of tricking anyone into thinking it’s a true story about a modder trying to finish their dead friend’s project and slowly descending into madness. But it doesn’t have to.

Personal Pick

In addition to our main Game of the Year Awards 2023, each member of the PC Gamer team is shining a spotlight on a game they loved this year. We’ll post new personal picks, alongside our main awards, throughout the rest of the month.

Myhouse is freaky enough all on its own that it kept me on edge for hours, shifting under my feet so seamlessly that I still ended up questioning what was real by the time I “finished” it—at which point I’d actually only seen a fraction of what this endlessly messed up mod was waiting to spring on me.

The journal that accompanies Myhouse is one of many meta layers to its story, hiding several seemingly innocent details that tie into the artifacts you’ll find scattered throughout the house as reality starts to fracture around you. My favorite bit of it is how it plays with the form of modern Doom modding, hinting at the difference between the 3.5MB Myhouse.wad and 65MB Myhouse.pk3:

“I tried to delete myhouse.pk3 but I keep getting a ‘file in use’ error. I don’t think the map will let me. I’m going to post it on Doomworld tonight, but I don’t want anyone playing anything other than the original vanilla release—whatever this map is doing to me, I can’t let it do the same to others.”

In other words: Map’s haunted.

Seriously, this house isn’t just haunted. It’s “The Scooby Gang would bail after 30 minutes” haunted. It’s “I reflexively blurted out the word NO at my monitor at 10 pm” haunted.

There was no way out, just a way to go further in, which is when Myhouse.pk3 really began.

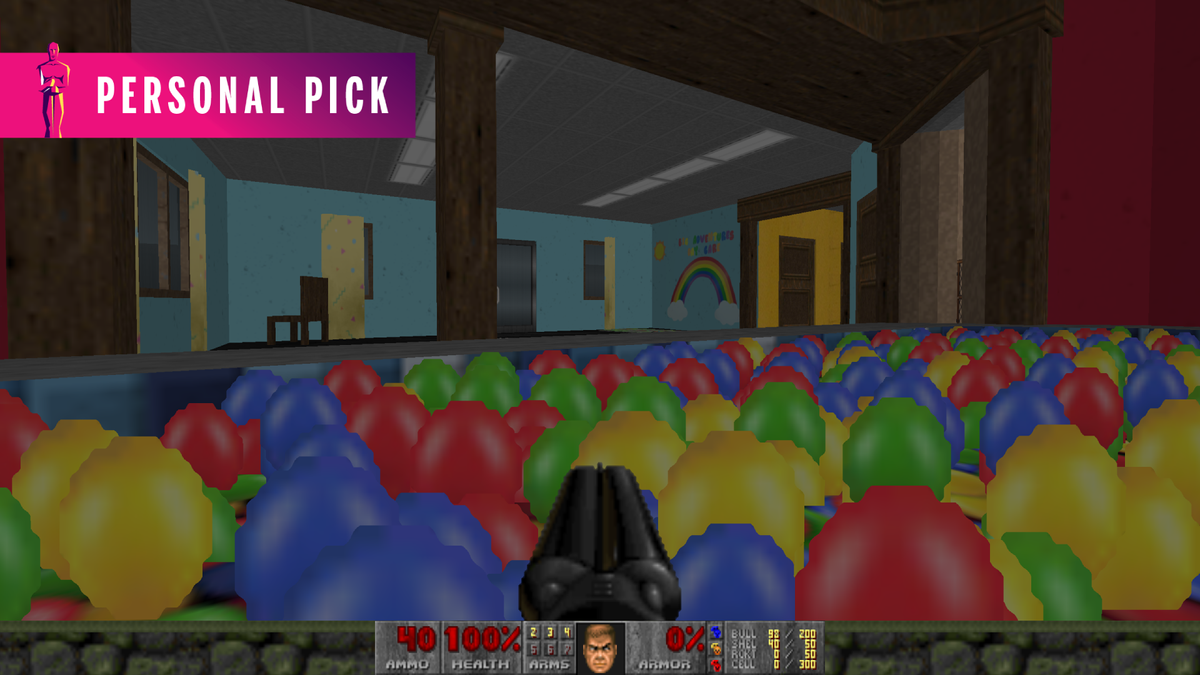

It starts small, playing tricks on you that briefly make you question your own memory. I shotgunned my way through the house’s oddly arranged bedrooms, cleared out the den downstairs, and then headed out into the yard for a power-up that taunted me through a window. Outside I peered through the windows befuddled: the enemies were alive again. And that power-up was gone. So I went inside to do it all again, and… wait a second. That hallway wasn’t shaped like that before, was it? No, that door’s definitely new—but the angles of the house are so bizarre, it’s easy to think you just didn’t see it the first time through.

When I found the final key to make my way to the exit, a blank wall was sitting where the front door used to be. There was no way out, just a way to go further in, which is when Myhouse.pk3 really began.

Or maybe it began the moment I opened a door and discovered a stark black-and-white modern room had appeared out of nowhere in the middle of the cozy wood paneled house like an invasive species. Or maybe it began after I did find my way to the exit and GZDoom dutifully booted up Doom 2’s second episode, Underhalls. The level offered the relief of a few minutes of straightforward shooting… but it dumped me back into Myhouse as soon as I finished it. It took me dying partway through one of a seemingly impossible number of layers to fully grasp how wildly inventive this mod is.

A few videogames have successfully played with meta storytelling and breaking the fourth wall as effectively as Myhouse, like Undertale or The Beginner’s Guide. But I think there’s a distinct difference here—in those games, you can feel the author reaching through the screen, speaking directly to you, the player. They surprise you and subvert your expectations by acknowledging that this is a game, and the game knows it’s a game, and the person behind the game has thoughts about how you’re playing it.

Myhouse doesn’t care about any of that. It just wants to feel unknowable.

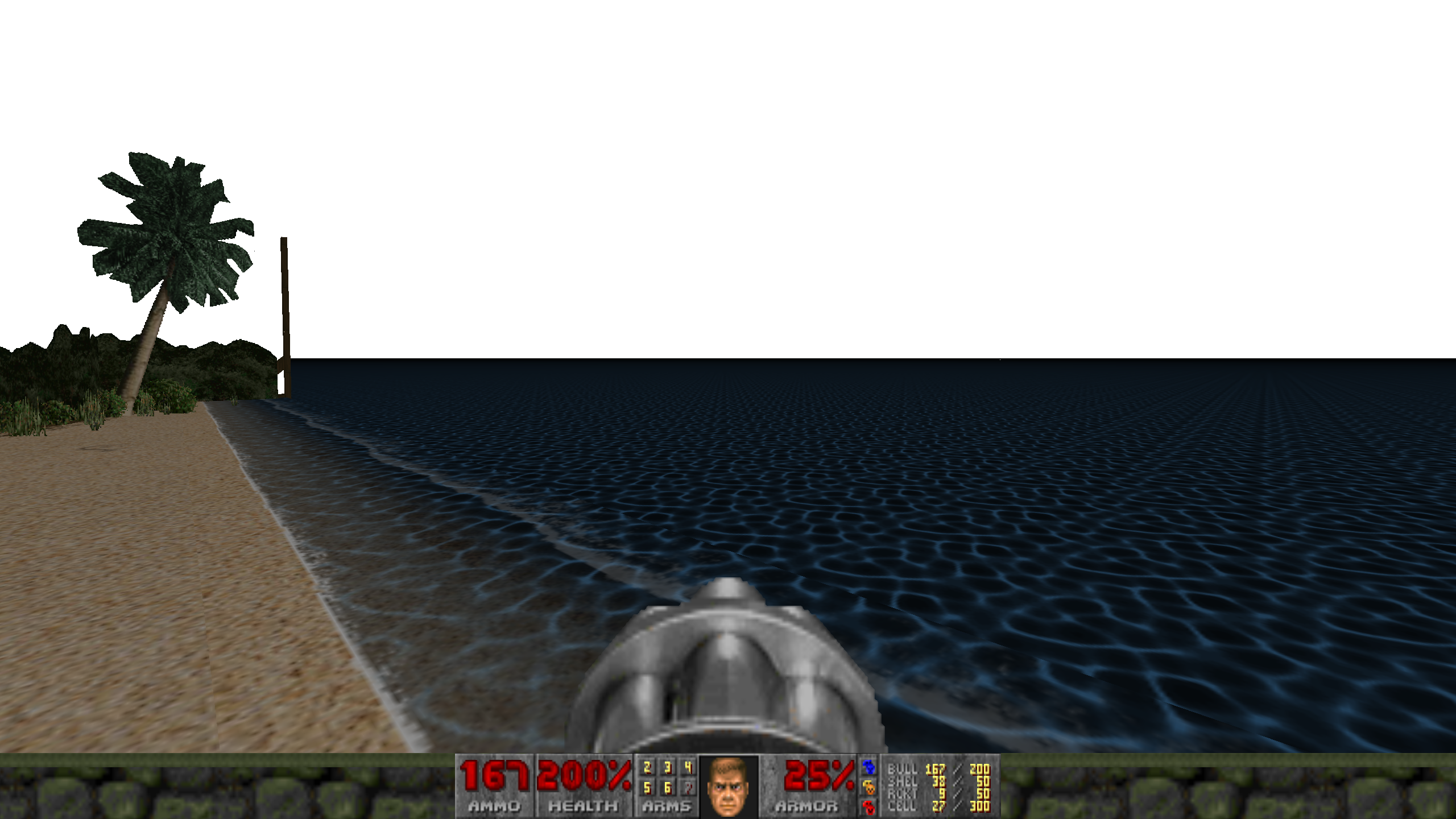

The best found footage film can make you suspend your disbelief, but a found .wad—which might be a genre of just this one game?—can actually be cursed. It weaponizes how you expect a game to behave against you, unfurling into a mystery that could easily keep you occupied for several hours. What makes Myhouse really great is that there’s thought and meaning behind all of it, the significance of its jarring liminal spaces tying back to that simple Google doc. Nothing here is just wacky randomness, but in the moment it does still feel disorienting and completely unpredictable.

Doom is 30 years old, and yet someone still used it as the vessel to build one of the smartest, most intricate games of the year. What a legacy! Play it once without looking up where to go or what to do—just explore. When you think you’ve seen what there is to see, look up a guide and figure out just how much more this house is hiding.