Thinking back on the time I spent forming my Victoria 3 impressions with a preview build of Paradox’s forthcoming grand strategy game about the 19th century, there are some definite highlights: enacting some early voting rights legislation in Sweden, reforming the Brazilian tax code, and abolishing slavery in the United States without triggering a bloody civil war. You set out in Victoria 3 with grand ambitions, but what I found was that in the moment-to-moment play, what I spent most of my time doing was building things.

There’s always something that needs building. I want trains to reach my iron-rich provinces, I need more universities to produce more qualified applicants for technical jobs, more ports to handle my trading routes that bring in materials I can’t produce and ship out the goods I’m selling abroad to make up for my constantly ballooning construction budget. I need more logging camps, more barracks, more tool shops, more farms.

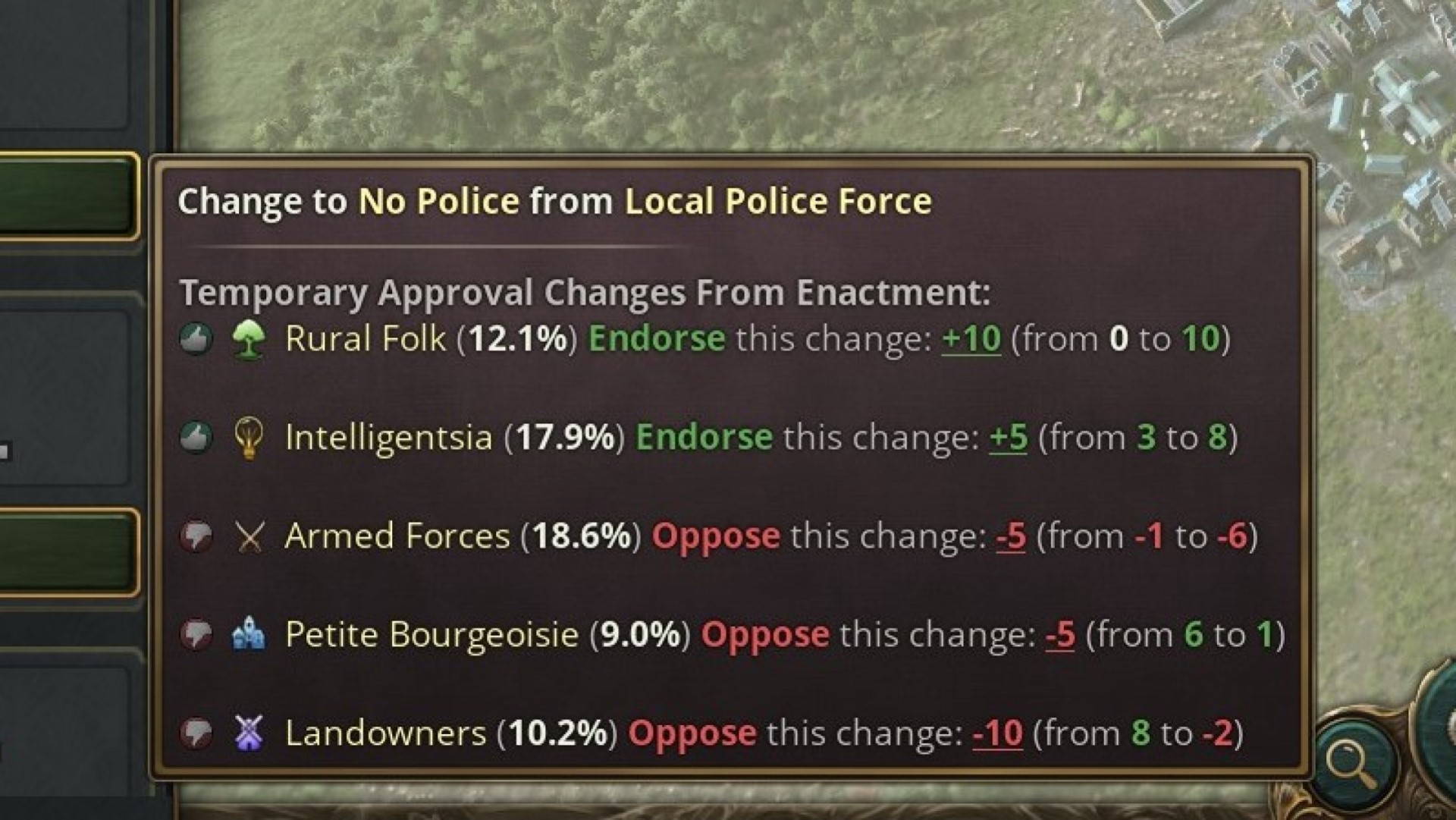

Victoria 3 is not simply a building game, however. As game director Martin Anward explains to me, it’s a game about agency. No matter which nation you choose to lead in Victoria 3, it’s going to be full of different kinds of people, each with their own goals, abilities, and checks on your own exercise of supreme power. As circumstances in your country change, these groups will by turns find common cause with one another or find themselves at cross purposes. Figuring out how much power you have, and how much you’ll need to cooperate with those groups, is at the heart of Victoria 3.

An example may be helpful here. Perhaps I want to switch to a more efficient filing process for my government workers, expanding its taxation capacity and generally making things more efficient. To do that, I’ll need more bureaucrats and clerks – but my education system is non-existent and more than half the country is illiterate. One answer to this dilemma is public schools – but the aristocrats and clergy, both powerful and influential groups in my country, are dead-set against it, making passage of a public schools bill next to impossible for the foreseeable future.

To create a public education system, I’ll need to look around for groups that already support this idea. Trade unionists are all for it, but in the 1840s, they’re marginalised and have no political power whatsoever. If I can change that, and get them represented in the government the next time we have an election, the future of public schools might get a bit rosier. Simultaneously, I’ll need to look around for opportunities to undercut the aristocracy and the church – but that will likely cost me valuable revenues later on, and risk radicalising those interest groups.

There’s a lot of information to sift through in Victoria 3, and the developers have made some smart choices in putting it at your fingertips. The new lens system provides shortcuts to much of this, allowing you to pull up the appropriate panels and map mode for trade, military, politics, and more.

Paradox has also made some great leaps forward with its approach to tutorials in Victoria 3. When you begin a new game, Victoria 3 prompts you to choose a goal. You can pick economic dominance, military supremacy, or egalitarian society. You can also choose to learn how to play. You can select from four suggested start nations, or choose your own – either way, Victoria 3’s helpful journal system will provide a constant supply of tasks to complete. When playing with the learn to play objective active, the journal will also tell you exactly how to perform each task, and provide the rationale for it – but only if you ask for it. Early objectives include buttons reading “show me how” and “tell me why,” along with one that lets you skip a particular lesson entirely.

Anward tells me Victoria 3’s tutorial design is an attempt to solve a couple perennial problems with Paradox’s approach to date. The team wanted to avoid players feeling like they’re being “railroaded” through a heavily guided experience, and to allow players to pick the nation they want rather than forcing them to start out somewhere specific, like Ireland or Italy or Spain, for instance. Using a journal system that works with any nation also alleviates the need to completely rewrite the tutorial every time there’s a significant update, making it less of a persistent issue down the road.

It works in conjunction with the nested tooltip system introduced in Crusader Kings 3 to make learning Victoria 3 – the latest in what may be Paradox’s most notoriously obtuse grand strategy games – the smoothest process it’s ever been, although you will naturally be at an advantage if you’ve already put some time into Hearts of Iron IV or Crusader Kings 3. For those of us in that camp, having the option available to skip over some of the basics means the ‘tutorial’ mode in Victoria 3 is still well worth playing a couple times, and you can get right to the parts that deal with new ideas.

During my preview of Victoria 3, I never found myself involved in a major war, and so I don’t yet have a fully formed set of impressions on the diplomatic play system and combat. While I’m excited by Victoria 3’s novel approaches in both these spheres conceptually, in practice they felt a bit flat during my campaigns. Diplomatic plays that cropped up almost always seemed to function as countdown timers to war rather than opportunities to solve a crisis in another way – but this may be down to the limited circumstances in which they arose in my specific games.

As Paradox has explained, you don’t have any direct control over combat units in Victoria 3, and this is certain to be a controversial move. In Brazil I fought back the Ragamuffin revolt across two fronts, but my role in it was simply to appoint generals and assign them to fronts where troops were most urgently needed. It’s a system that makes sense thematically – presidents and prime ministers aren’t concerned with operational command of individual brigades and divisions, after all – but practically speaking it left me with little to do beyond building new arms manufacturing plants and looking up the best overseas deals on cannons and warships.

The wars I fought were also small enough that I never felt any real economic sting from them, although Paradox has said that making war costly has been a major design goal for Victoria 3. I’ll be eager to see how larger, longer conflicts impact my economy when I finally get my hands on the release build, but in the localised border wars I fought, the cost – both in terms of treasure and lives – was easily manageable.

Veterans of Victoria II will no doubt be a bit shocked at how much more abstract trade has become here. Trade routes between nations are either open or they’re not, you don’t have to concern yourself with the amount of the goods you’re importing or exporting – the respective market conditions will determine the quantities you wind up shipping. This strikes me as another smart move – it’s one less thing to /do/, but it simplifies the decision-making process and simultaneously produces a more believable simulation of an import/export economy.

There are things I still wish were easier to find in Victoria 3 – for instance, a concise list of my open trade routes, or a way to quickly open the information panel for a country when I’m zoomed in looking at one of its component states. I wish the building queue would appear even when I select a state where no construction is going on. These are quibbles that are offset many times over by the number of smart design decisions that combine to make playing Victoria 3 a shockingly pleasant experience.

Delighted as I was by the beautiful paper map and painterly landscapes of Crusader Kings 3, Victoria 3 is Paradox’s most gorgeous game to date, hands down. You can almost feel the zephyrs of ocean breeze as you zoom in to look at your coastal cities like Stockholm and Boston. The autumn leaves swirl as the train leaves Brussels on its way to Luxembourg, and pulling back reveals another gorgeous illustrated paper map, with up-to-the-moment cartographic details labelled in a stately surveyor’s font. The presentation, from the map to the UI, is a visual feast of pleasant semiotics.

It’s still early days, though. The Victoria 3 release date is October 25, and the preview build we played still had some admittedly rough edges: coding strings in place of explanatory text in a few spots, and some text tagged with “the player should never see this.”

Still, the preview was encouraging. The Victoria 3 dev diaries over the past year have painted a wildly ambitious picture of a kind of gestalt grand strategy game, a Leviathan built out of mutually dependent systems that are all part of a unified whole. Based on the time I’ve spent with it, I’ve got to say that it seems like they’ve managed to pull it off – or at least come damn close.

“We wanted a game where the economics feeds into the politics, and the politics feeds into the economics,” Anward tells me after the preview period wraps up. As he explains, Victoria 3’s big idea is giving its little people true agency to shape their own futures. “How ideologies were shaped, and how people came to want or not want the things they want or don’t want in the game is one of the areas where I think Victoria 3 really shines, and where it’s a very different game from most.”