Crusader Kings 3 had always surprised me with its deviancy, but I did not expect to be operating the most incestuous bloodline in the Sahara. My queen, of central African nobility—who had deftly altered the laws of succession to ensure that our ancestral titles would prioritize women instead of men—was decades into an illustrious reign when one of her ne’er-do-well sons confronted her in the ballroom. Did he desire a promotion? A new plot of land? No, far worse; he simply wanted to sleep with his biological mother.

I knew the middle ages were lousy with corrupted DNA, but that was a bridge too far. I rebuffed her prodigal heir, who thankfully never raised the issue again.

My queen shook off her mortal coil a few years later. She drank herself to death, which seemed fitting given the depravity of her brood. I’d be depressed too! The kingdom passed to one of her sons, (not that one), who was dimmer and more gullible than his mother, but did know his way around a military barracks. He was also gay; a cardinal sin in this brutal epoch. No matter, we soldiered on with our disinterested wife, expanding our territory towards the Atlantic ocean.

Everything was going to plan until his cousin came knocking on our door. Yes, that’s right, he wanted to sleep with us too.

“[Crusader Kings 3] looks at a bunch of rarefied people, and fundamentally, a lot of them end up banging their cousins.”

—Dr. Eleanor Janega

I was still in the early game of this particular run, and the gene pool had already been fouled up beyond imagination. This is a videogame that both retells and satirizes the beguiling centuries before the renaissance—a time of chattel serfdom, land-brokering marriages, and wars of greedy plunder. And yet, there is a voice in the back of my head that asks, at every ridiculous juncture, is Paradox overdoing it? Were the Middle Ages actually as horny, and murderous, and wanton as Crusader Kings presents them? Were intimate family members constantly begging for sex?

I needed answers, so I reached out to Dr. Eleanor Janega, a medieval historian, who also happens to be a devout fan of Crusader Kings 3. The answer, as expected, was complicated.

Dr. Eleanor Janega is a scholar of medieval history at the London School of Economics who enjoys grand strategy gaming in her spare time. She is also the author of the blog Going Medieval.

“[Crusader Kings 3] looks at a bunch of rarefied people, and fundamentally, a lot of them end up banging their cousins.” says Janega, who graciously took time out of a party she was attending to answer my stupid questions. “The thing I always bring up is Eleanor Aquitaine. Her first husband was King Louis VII, and she gets that marriage annulled because she doesn’t like him that much. And how did she get it annulled? On accounts of ‘consanguinity’—basically that they were second cousins. But then, Eleanor immediately turns around and marries the King of England, who was her first cousin. It was an incredibly small dating pool.”

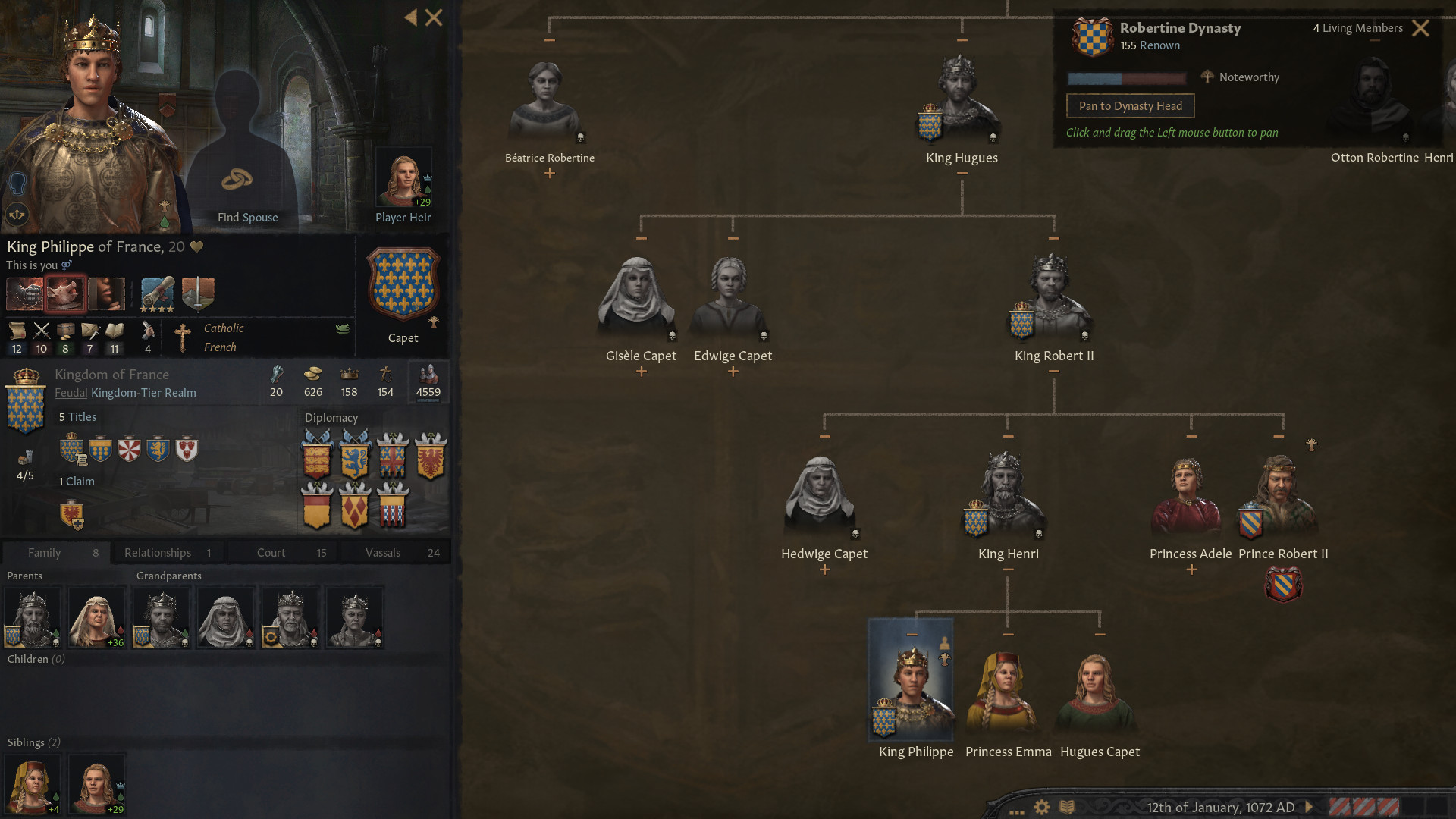

I usually orient my Crusader Kings campaigns around the minor nobility of the world. With the reins of a minor Holy Roman Empire principality, I try to wrest myself free from the thumb of the Pope, or my liege, or the barbarians at the gates. Janega tells me that in those environments—a tiny court and an insulated nobility—incestuousness was more common.

She points to a 12th century treatise titled De Amore which served as a field guide to the romantic frivolities of high society. In it, the author Andreas Capellanus states that any royal worth their salt may only fall in love with the middle class, lower nobility, and upper nobility. Commoners, on the other hand, were physically incapable of love, “like the beasts of the field.” With that narrow of a scope, maybe you can understand why a vassal might take a second look at their aunt.

“[The ruling class] was like three percent of the population,” continues Janega. “And London is only like 10,000 people at the time.”

But Janega also tells me that Crusader Kings 3 does take plenty of historical liberties in the name of delivering a fun gameplay experience. If you are familiar with the series, you have no doubt encountered the Littlefinger-esque treachery that constantly circulates through the throne room. A distant heir wants to press a specious claim to the crown, and they’re willing to murder you to expedite their ascension. In general, says Janega, royal lineages were a lot more ironclad than Paradox makes them out to be—monarchs were not constantly getting picked off in the ballroom.

“There’s a lot less outright murder in history, but you do get complex plots,” says Janega. “A good example is King John of Bohemia. He’s always going to tournaments and wars and he’s never at home. His wife hates him. So she tries to do a coup where they put their child on the throne right away. John finds out, and puts her under house arrest. So, you have plots, but a lot of the time it doesn’t involve murder.”

Of course, when cloak-and-dagger schemes don’t work out, you can always raise an army from the peasantry and campaign against whomever is on your border. Warfare in Crusader Kings 3 is infamously structured with all sorts of genteel guardrails; you need a suitable casus belli, Latin for “cause of war,” and enough reputation within the upper crust of medieval movers and shakers to even invade a contested barony in the Italian highlands. I was curious to know if this was also mirrored in the global record. Did the dukes and duchesses of antiquity really need to get around all sorts of red tape before mustering the troops?

If you want to invade Pomerania? Go right ahead.

—Dr. Eleanor Janega

“It depends on how much of a dick they were. In France, casus belli laws are a huge deal. They have a big kingdom with a ton of vassals, so they’re always checking how chivalry works, because everything is down to courtesy. If you upset that balance, things can get difficult,” says Janega. “But there’s less of that in in-between places. Milan is a constant football. The French are taking over, then the Holy Roman Empire, and they don’t care about casus belli at all. It varies.

“But it’s definitely true, if you’re the Holy Roman Empire, you’re not going to invade Bohemia. They have too much power and they’re too rich. But if you want to invade Pomerania? Go right ahead. There’s side quests all the time.”

Overall, Janega believes that Crusader Kings 3 does a reasonably good job of simulating the contours of medieval melodrama. But there is one last elephant in the room. Historical scholarship has focused less on the throne room in recent years because of the point Janega raised earlier; nobility is an exceptionally small world, and it offers an extremely unrepresentative picture of what it actually felt like to live in the Middle Ages.

Paradox, of course, pays no mind to farmers and herders. Crusader Kings is an exceptionally vivid playback of monarchical politics, but the focus of its intrigue is entirely on the palace. So perhaps there is room for a game that turns the genre on its head, with a story centered around those under the boot of their oppressors.

“On one hand I love when any kind of medieval entertainment is out there in the world, but it would be cool if someone made an RPG about the peasant rebellions. There are peasant rebellions in Crusader Kings all the time, but why can’t you play as the peasants?” finishes Janega. “Like, how do you build coalitions with other peasants? How do you get the preachers on your side? I think that would be incredibly fun.”

I wholeheartedly agree. For as much as I enjoy the carnal derangement of my fellow aristocrats, there’s never been a better time for a medieval saga from the point of view of the downtrodden. Paradox, if you’re reading this, let’s spotlight those good, God-fearing people who’ve been indentured by all these foppish sickos under the royal crest. Playing as Henry VII is all well and good, but you know what’s even better? Lopping his head off and dragging the body through the streets.